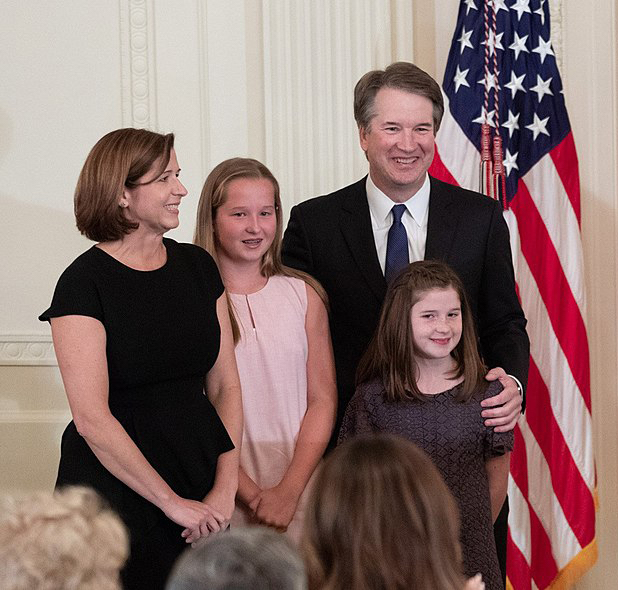

wikimediacommons

On Saturday, Brett Kavanaugh ’87 LAW ’90 was quietly sworn into the Supreme Court, amid resignation from Yale students, alumni and faculty who led an organized campaign against the justice in the weeks leading up to the confirmation vote.

The Senate’s narrow decision to confirm Kavanaugh — he won 50–48 — comes after weeks of bitter debate and protests at the University. In early September, Kavanaugh’s confirmation seemed almost certain, but three allegations of sexual misconduct — including one that allegedly occurred on Yale’s campus — called the justice’s path to the highest court into question. The debate also thrust Yale Law School into the national spotlight, as students and faculty reckoned with allegations against one of their own.

Following Kavanaugh’s confirmation over the weekend, activists who organized against Kavanaugh expressed dismay that the 50 senators who voted in his favor disregarded the allegations of sexual misconduct against the justice. Among 11 Yale students and alumni interviewed by the News, 10 said that they were troubled by the Senate’s decision, and six students and alumni added that they were alarmed by the implications of a conservative majority on the Supreme Court.

“Anyone with a conscience should be upset right now,” said Valentina Connell ’20, who helped organize the “Solidarity with Survivors” rally in support of Kavanaugh’s accusers and victims of sexual misconduct. “Not only has Kavanaugh been accused by three incredibly courageous women of sexual misconduct, but the way he conducted himself during his hearing was extremely unprofessional — not the way I would want anyone who sits on the highest court in the land to act.”

Amid the allegations, students quickly organized — forming the activist group Yale Law Students Demanding Better — to call on Yale administrators and elected officials to oppose Kavanaugh’s confirmation. Thousands of Yale alumni penned open letters supporting the accusers, one of whom, Deborah Ramirez ’87, alleges that Kavanaugh inappropriately exposed himself to her at a party on Old Campus while they were classmates at Yale. On Sept. 24, over 300 Yale Law community members staged a sit-in at the Law School — the largest demonstration at the school in recent history — calling on its Dean Heather Gerken to take a stronger stance on Kavanaugh’s nomination. That same day, over 100 law students protested the nomination in Washington, D.C. Dozens of Yale Law professors urged the Senate Judiciary Committee to conduct a fair and deliberate confirmation process, and on Sept. 28, Gerken joined the American Bar Association in a call for an investigation into the allegations.

But after Kavanaugh’s confirmation, following a less than weeklong FBI investigation into the sexual assault allegations against Kavanaugh, Gerken did not respond to request for comment. Ramirez and her lawyer Lara Bergthold declined to comment for the story.

In interviews with the News, students and alumni who organized protests said they were disheartened by Saturday’s outcome.

“I am overwhelmingly disappointed. I am disappointed that the Senate did not listen to the calls of millions of Americans, especially survivors,” said Briana Clark LAW ’20, who helped organize the Law School sit-in with the group Yale Law Students Demanding Better. “I am disappointed that the Senate did not listen to thousands of university professors regarding concerns over Judge Kavanaugh’s temperament and partisanship. I am disappointed that the FBI investigation was not only unfair, it was impartial, incomplete and appears to be a complete ruse.”

Rebecca Steinitz ’86, who cowrote an open letter on behalf of Yale women in support of Kavanaugh’s accusers, called the confirmation a “disgrace” and said that the Yale alumni who “lied to defend Kavanaugh” and Kavanaugh himself are “the worst of Yale.”

Others compared Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the election of President Donald Trump in 2016.

“I believe the Kavanaugh confirmation is a simple illustration of … how power-hungry the country’s representatives are and their ideologies of disregarding the voices and lives of women, people of color and other marginalized people,” said Jeniffer Bañuelos ’21, a board member of Latina Women at Yale.

Mary Ella Simmons LAW ’20, another organizer with Yale Law Students Demanding Better, said that she was deeply alarmed by the way Kavanaugh used his connection to Yale Law School as a “moral defense” against the allegations against him. In his confirmation hearings, members of the Senate Judiciary Committee asked Kavanaugh about his drinking habits during his young adulthood. He responded, “I got into Yale Law School. That’s the number one law school in the country. I had no connections there. I got there by busting my tail in college.”

Still, Simmons said she was encouraged by the support for fellow activists and survivors of sexual assault throughout the confirmation battle.

“I am proud of the way my classmates have made their concerns about Kavanaugh and their solidarity with Dr. Blasey Ford so well-known, despite the school’s slow and tepid response,” Simmons said. “We’ve begun some hard conversations on campus and I know this is just the beginning of the law school community’s reckoning with its role in this process.”

Despite Gerken’s silence, other members of the Law School faculty have openly criticized Kavanaugh. In an op-ed in Politico Magazine, former Dean of Yale Law School Robert Post LAW ’77 argued that Kavanaugh’s presence will undermine the court’s claim to legitimacy and “damage the nation’s commitment to the rule of law.”

“Judge Kavanaugh cannot have it both ways,” Post wrote. “He cannot gain confirmation by unleashing partisan fury while simultaneously claiming that he possesses a judicial and impartial temperament. If Kavanaugh really cared about the integrity and independence of the Supreme Court, he would even now withdraw from consideration.”

Many students interviewed by the News said they are concerned by the potential impact of Kavanaugh’s appointment on reproductive rights, immigration, healthcare and the environment. Miranda Rector ’20, co-president of the Reproductive Justice Action League at Yale, said that the presence of two Supreme Court Justices who have been accused of sexual misconduct — Clarence Thomas ’74 and Kavanaugh — speaks to a “lack of concern or care for anyone’s bodily autonomy.” In 1991, Anita Hill LAW ’80 alleged that Thomas sexually harassed her while they both worked at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

But not all Yale students and alumni condemned the confirmation vote. Kavanaugh’s former fraternity brother Mickey Kappele ’87 said he was happy for his old friend. He criticized the politicized confirmation process, saying that it did not have to be “a big charade.” He added that many of his old college friends — mostly fraternity members, former classmates in Timothy Dwight college and athletes — were similarly relieved that Kavanaugh was confirmed.

“[Kavanaugh’s protesters] don’t know Judge Kavanaugh,” Kappele said. “If they did know him, I’m sure they would feel differently.”

On Saturday, more than 100 New Haven community members protested Kavanaugh’s confirmation outside the New Haven Superior Courthouse.

Serena Cho | serena.cho@yale.edu

Alice Park | alice.park@yale.edu