On Friday I attended the conversation “Building Dialogue around John Wilson’s ‘The Incident’” alongside about 20 other observers from Yale and New Haven. Members of the community came together to view and discuss exclusive pieces included in “Reckoning with ‘The Incident’: John Wilson’s Studies for a Lynching Mural,” a forthcoming exhibition that will travel to various college and university art museums between January 2019 and May 2020. The talk was lead by Bix Archer ’19, as well as Elisabeth Hodermarsky, acting head and Sutphin Family senior associate curator of prints and drawings, and Margaret Spillane, an English professor.

After being handed index cards and small pencils, we were asked to write down our thoughts. As I moved throughout the space, I first encountered disembodied images that appeared normal and isolated from one another. A hand on a shoulder, a twisted foot, hands gripping rifles … the remnants of rope fixed securely around a tree branch. These pieces were easily recognizable and held a simple appearance, but upon closer inspection, detailed lines and shading formed vivid textures, skin and bark. Each study was produced by Wilson in 1952 using crayon, charcoal, watercolor and India ink. Each were created for a specific purpose, informing Wilson in his later work on a massive mural that would soon become famous — and seemingly lost forever.

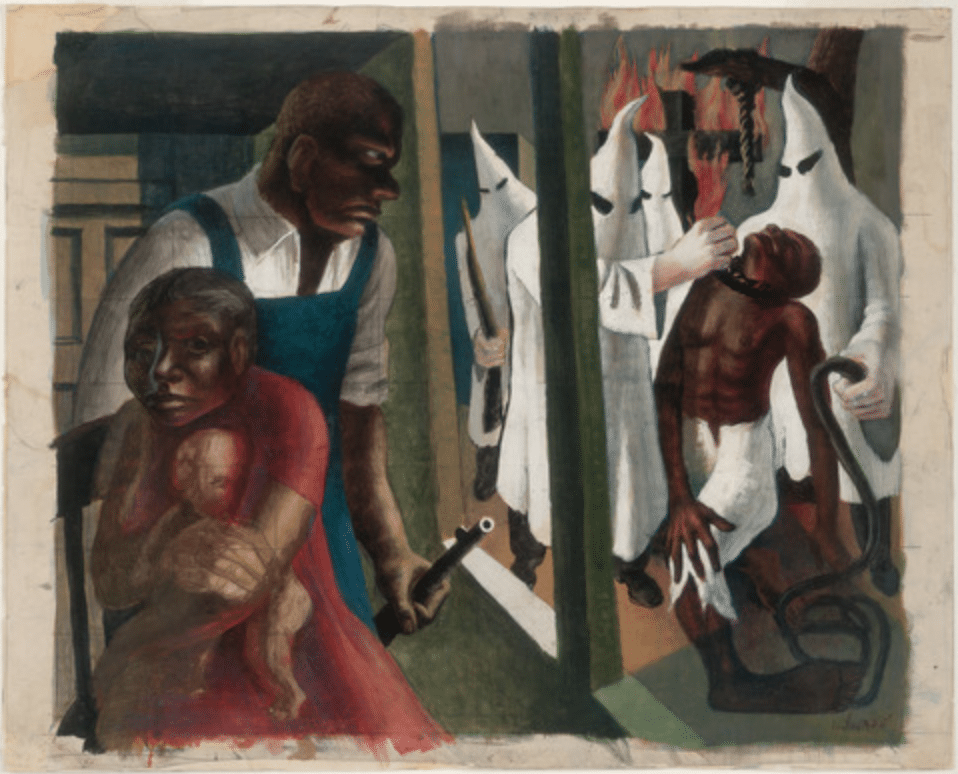

John Wilson created “The Incident” while residing in Mexico from 1950–56. Wilson was hoping to study alongside the famous Mexican artist and painter José Clemente Orozco, inspired by the political and social activism demonstrated in his work. Unfortunately, Orozco passed shortly before Wilson’s arrival. Remaining committed to the theme of human suffering, Wilson depicted a young African-American family witnessing a racial terror lynching outside of their home. A woman is turned slightly away as she clutches a baby in her arms, while an older man behind her grips a rifle and stares in the opposite direction. Following his rage-filled eyes, one can see that outside, the Ku Klux Klan is cutting down the body of a black man from a tree. There is a frame structure that separates the two spaces, implying a fragile interior scene and, perhaps, an ineffective divider that fails to protect the family.

The piece was preserved for quite some time before being painted over, a tradition at La Esmeralda, Mexico’s national school of art. According to the gallery’s website, the Yale University Art Gallery’s collection brings together “for the first time nearly all of Wilson’s preparatory studies for his piece — including drawings, paintings and prints.” Wilson’s art is breathtakingly beautiful, and composed of many functioning parts. I was particularly struck by the study of Wilson’s wife Julie, which was a larger study for the purpose of drafting the father figure in the mural, specifically, the shape of the head and the lighting of his face. Hodermarsky discussed how Wilson also used gridding to allow him to scale up to a larger design.

In creating this piece, Winston could recall strong childhood memories of seeing imagery of lynchings in the newspapers his father read. The personal nature of this work is clear, an invocation of trauma that is hard to handle. As I viewed each of the pieces one by one, I found myself grappling with the same themes that Wilson spent years working through in his art. The violent images that appear in the exhibit are deeply upsetting and force the present viewer to work through these thoughts in the context of today’s racial climate.

“We felt an urgency to bring this work together,” said Hodermarsky, explaining that the purpose of the exhibit is to “examine this one black artist’s experience with reckoning with the past” and racism in America.

I admired how passionate Hodermarsky was about her subject, and how attentive she was about handling the subject matter properly. One onlooker pointed out the risk of displaying such images in that they are harmful to those who continue to experience racial oppression and violence, to which Hordermarsky responded thoughtfully that the YUAG is constantly thinking about how to protect viewers. A few strategies that the museum plans to employ includes stationing the exhibition in a mezzanine over the fourth floor, with a description of the show at the entrances. The YUAG is also considering hiring a trauma counselor for the gallery for conversation. These are part of a very intentional effort to prepare viewers for the sensitive and potentially triggering content.

I wasn’t sure what to expect before entering the room, but I’m glad I became witness to Wilson’s work on such a thoughtful and laborious piece. While the exhibition won’t return to the YUAG until January 2020, the museum has made an active effort to begin dialogue on this work before its premiere in 2019.

Alexus Coney | alexus.coney@yale.edu