Courtesy of Johnathon Henninger

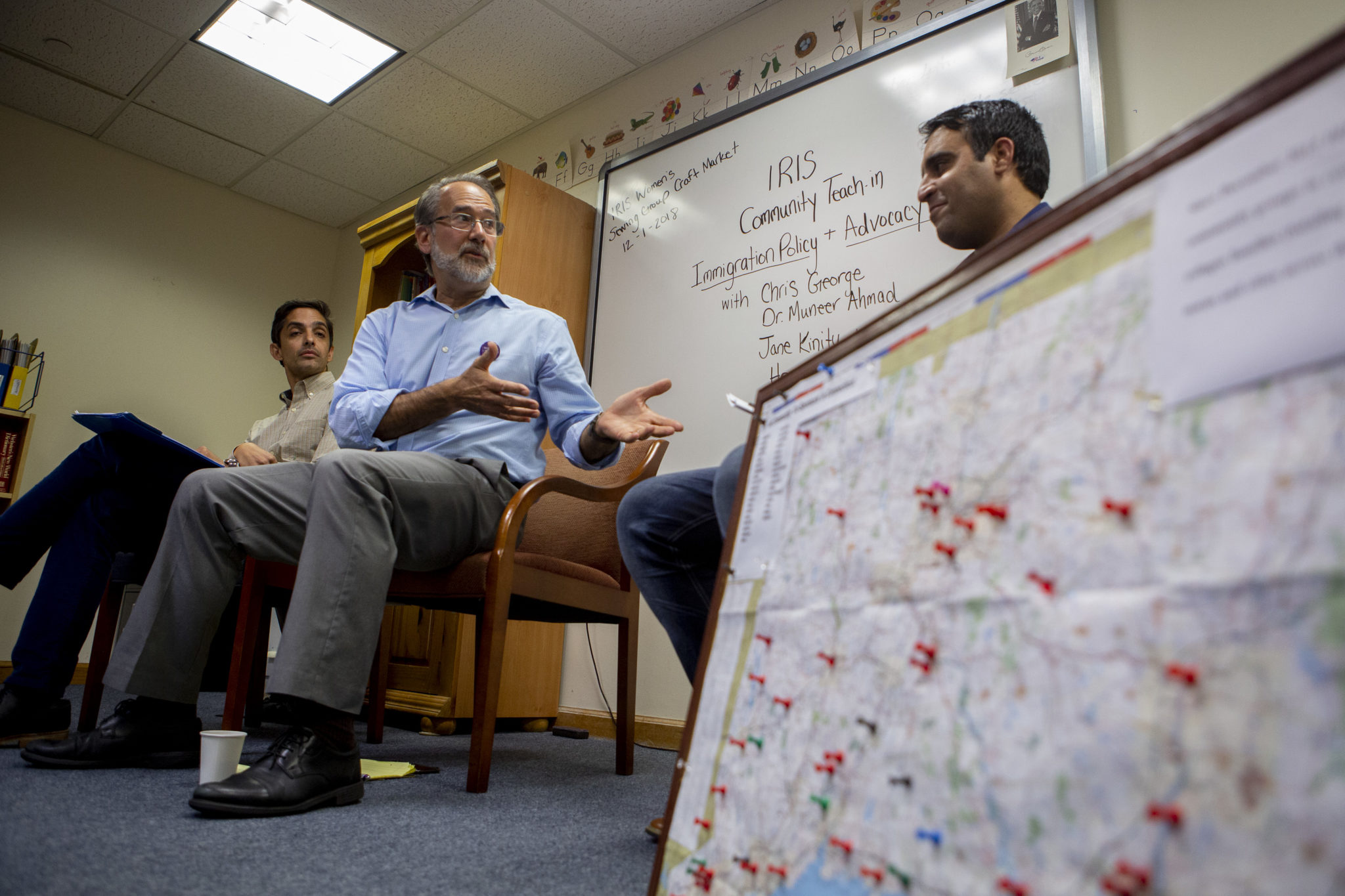

About 30 New Haven residents and volunteers gathered over coffee and refugee-made baklava at the headquarters of local nonprofit Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services on Tuesday night. The workshop, entitled “Immigration Policy and Advocacy 101,” hosted a panel made up of IRIS executive director Chris George, Yale Law School professor Muneer Ahmad and Afghani refugee representative Hewad Jhan Hewat.

According to IRIS Volunteer Program Specialist Kimberly Gill, the workshop was part of an initiative to help IRIS volunteers as well as the greater New Haven community become better informed about issues that impact refugees in New Haven, and how to advocate for them.

“A lot of people have perceptions about undocumented immigrants, of anyone who has a different status and is not American,” said Tabitha Sookdeo, a previously undocumented immigrant from Guyana who now works as a donor and grant relations specialist for IRIS. “So one of our big strategies is to hold events like these where we can invite the community and talk about any questions that people may have.”

When refugee families first arrive in New Haven after long and exhausting travels, IRIS members and volunteers are there to serve them a hot meal and begin their resettlement process, George said.

During the panel, George explained that resettling refugees was a public- and private-based partnership — the U.S. government performs background checks and delineates guidelines for their treatment, while resettlement organizations are responsible for welcoming and integrating them into American society.

Refugees are first assigned to nine national organizations, which then place them with smaller nonprofits such as IRIS. The location where a refugee is directed might depend on whether the refugee has any family or friends within the United States. If no such connection exists, they are arbitrarily placed anywhere in the country.

“The government sprinkles a little bit of money for refugee resettlement organizations, but we really have to roll up our sleeves and do all the work,” George said.

Hewat, a refugee under a Special Immigrant Visa for Iraqi and Afghani refugees, recounted working with U.S. troops in southeast Afghanistan in 2006. Hewat conducted media operations and spread awareness of U.S. education programs as well as their plans for spreading democracy.

However, when terrorist groups and insurgents learned of Hewat’s activities, they targeted him with death threats.

Hewat mentioned that though he was in imminent danger, with gunmen ransacking his family home, the vetting process that allowed him into the United States still took two years. During this time, Hewat was subjected to interrogation-like interviews and polygraphs to make sure he was “clean,” he said.

In speaking about his eventual transition to the United States, Hewat mentioned that it was difficult to adjust. However, he noted that he was thankful and grateful for the support he found in Connecticut.

“IRIS is like my family. I miss my father and my mother. But when I feel like I have to visit them, I see members of IRIS, and I feel like I saw my father, my grandmother, or my mother.” Hewat said.

Like many other nonprofits of this nature, IRIS’ services include helping refugees find jobs and homes, connecting them to healthcare, teaching them English and enrolling refugee children in schools.

However, George said that what makes IRIS especially successful is the organization’s use of a distinct resettlement model based on community involvement in refugee integration. Called “community co-sponsorship,” this trains volunteers to take the lead in receiving refugees into their own communities.

Now, more than 300 refugees in Connecticut have been resettled by community groups.

“It’s a model that has been successful in Connecticut. It’s really taken off like wildfire,” George said.

However, he suggested that this was not the case in other states, alluding to another major concern of the evening — the impact of the current administration on immigration policy and on both the perception and status of refugees living in the United States.

Panelists agreed that organizations such as IRIS have done an excellent job in carrying out their primary function of resettling refugees. But George said that these organizations have largely operated in the shadows, neglecting their other duty — to educate and engage the American population at large about their work.

“People running for public office were able to scapegoat refugees and undocumented immigrants. The oldest, dirtiest trick in the political book,” George said. “You pick people who do not have a lot of support, who do not have a lot of friends, and you turn them into the cause of all of our problems — people to be feared. And it worked, partly because refugees are not that well-known.”

An immigration law expert, Ahmad explained that refugees once had the highest status in international law amongst any category of migrant, as the United States is obligated under international treaties not to return individuals to countries where they may face persecution on the basis of protected grounds, such as race, national origin or political opinion.

According to Ahmad, U.S. President Donald Trump’s “Muslim ban” and his administration’s slashing of refugee assistance have led to the gradual denigration of refugees in the public eye.

“This happened by treating the refugee not as someone seeking protection, but equating the refugee with the stand-in of a Syrian, and the Syrian was equated with the Muslim, and the Muslim was equated with the terrorist,” Ahmad said.

Ahmad continued to speak about government practices that delegitimized asylum seekers and deliberately separated families as part of a systematic effort to close off all pathways to immigration, even legal ones. If you have questions regarding family immigration matters, you may consider consulting family immigration lawyers for professional assistance.

Elvira Mulyukova, associate research scientist in the Department of Geology and Geophysics and IRIS volunteer, told the News that the workshop had given her new perspectives about the refugee experience.

“I definitely learned a lot. I hadn’t thought about the refugees’ entire journey, from getting vetted to going on a plane to getting here,” Mulyukova said. “They have all this baggage of experience that I hadn’t really thought about.”

Meera Shoaib | meera.shoaib@yale.edu .