Windham-Campbell Festival

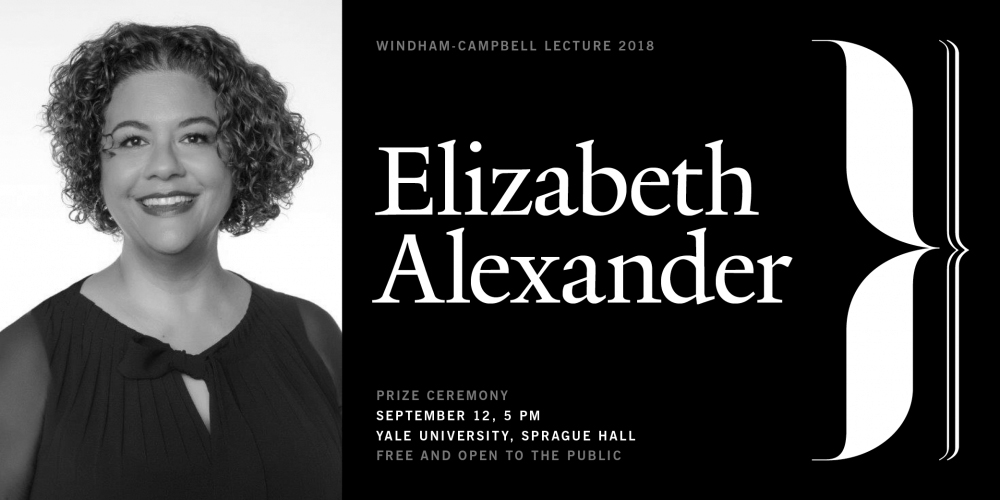

Quiet strains of cello music flowed from Sprague Hall on Wednesday at the 2018 Windham Campbell Prize Lecture where renowned poet Elizabeth Alexander ’84 spoke at length to a rapt audience, regally and gracefully detailing her answer to the prompt, “Why I write.”

Meanwhile, I was neither regal nor graceful; the sky had seen fit to dump about fifty gallons of water upon my thinly clothed and exhausted self, and while the guests milling about were cloaked in sophisticated prints and patterns, I was desperately willing my hair not to make too big a puddle below my (of course) extraordinarily squeaky chair.

“To make, to make, I wanted to make.”

Alexander spoke of her childhood, of how her semi-literate young self would hoard books with a ferocity, a ferocity I understood well, having packed up to 1300 books in my tiny Chicago bedroom within my 17.75 years of being able to walk. Her compulsion to read and create drew me in, so close in fact that I was no longer hunched over in a dripping chair, but on stage with her — and she was speaking with me, not to me. I was always the kid who kept a notebook ferreted away in my desk or in the crusty recesses of my backpack. When other kids went to the park for basketball, I stopped along the way and stared at the clouds, certain I had seen a word or shape within their puffy bodies. Alexander’s words ring especially true in my beginning weeks here at Yale. After a hazy summer of Netflix and the mishmash of too many graduation parties, I was thrown into a roiling ocean of paintings to paint, drawings to draw, words to write and places to go. Sometimes making is working, but when your hands itch and your mind sears with undone ideas, the notion in economics that “work is bad” just seems so utterly incorrect.

“I write because there is something virtuosic in me, too.”

Her lecture was not just a lecture. It was a concert, a concert in which the rich tones of Aretha Franklin echoed from on high and brought me back somewhere, maybe my hometown, maybe Yale, but some place where the wind whisked away my anxieties and I relaxed into the music. Such is the genius of Aretha Franklin, and such is the genius of Elizabeth Alexander for bringing the Queen of Soul to us one Wednesday evening in September. And Alexander truly is virtuosic — she did not lecture, but instead breathed her words like the poetry she is so revered for, urgently and passionately as if at a poetry slam in the Hopper Cabaret. Genius, I believe, is not a characteristic, but is instead the whole person. Elizabeth Alexander is her poetry, such that words emanate from her and you would see the effect, if only Snapchat had invented that filter.

“I write to perceive what I am living.”

Loss and purpose were central themes of Alexander’s lecture. Her husband passed away a few years ago and her healing process led to her 2015 memoir, “The Light of the World.” Though Alexander stated that the process was not cathartic, per se, she had still managed to write her way through that period of her life, gaining insights about why she is so attracted to writing and vocalizing these insights by quoting a friend: “I did not know why I sang until I sang at my mother’s funeral.” Purpose in the arts is often elusive. In science, it is easy to find reason for research, but writing and painting and making music have no concrete and collective basis for why they exist. Rather, the arts evoke feelings, and feelings inspire art. Authors’ purposes from the second grade — to explain, to persuade, to entertain — are insufficient to contain the spectrum of reasons, verbalized or kept within, for why we create. One could even say that, like the universe, our reasons for the arts are expanding, limitless in the emotions they capture and convey. And such a plethora of feeling would undoubtedly overwhelm, so we return, back to our laptops, back to our torn pieces of paper and broken pen. And we sit back, and we perceive.

“I write to make you feel what I feel.”

“I write to say what happened.”

“I write to commune.”

“I write … ”

Alexander does not just read poetry — she speaks it like it is a language wholly unique from any other in the world. And why shouldn’t it be? Language is a system of communication. Poetry is the same, different from its original tongue because of its grammar and structure (or lack thereof) and, most importantly, because of its feeling. Such is the mantra that ended Alexander’s lecture. Though she spoke in English, in simple, unadorned sentences. Her words churned, gaining power with each I write and becoming declarations of purpose instead of just statements of fact. And it is this purpose that was so powerful in its presence that made me forget about my wet hair and my lingering exhaustion, that made me forget myself and hold on tightly to that final declaration that made it seem as though the stars had perfectly aligned.

“I write to feel fully alive.”

Valerie Pavilonis | valerie.pavilonis@yale.edu