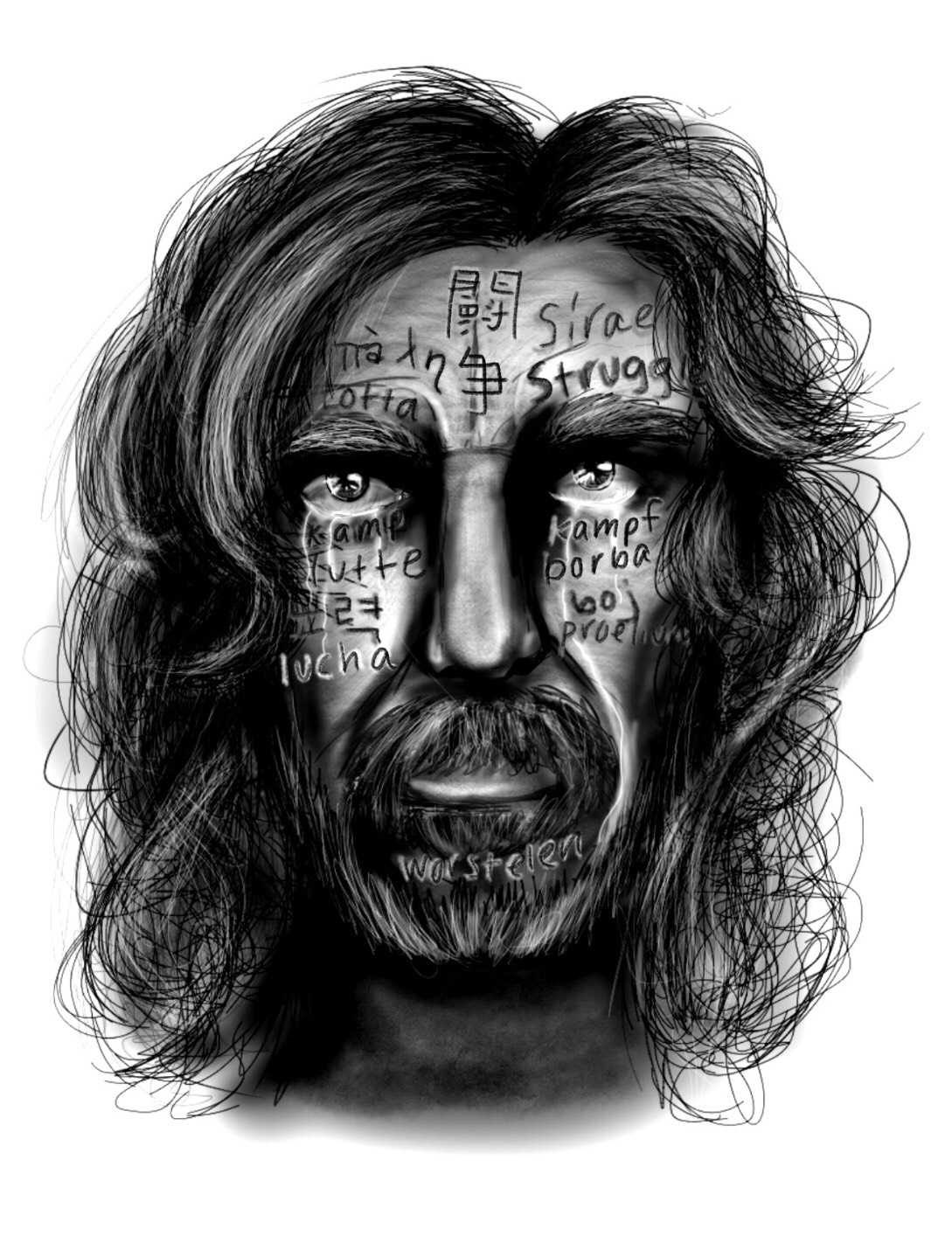

I’ve learned the hard way that there are certain books you should avoid taking on public transportation. Chris Kraus’ “I Love Dick” is one; Baratunde Thurston’s “How To Be Black” is another. But at least those books’ awkward titles can be quickly explained away. Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume, 3600-page autobiographical novel “My Struggle,” however, is a different beast. With its provocative title and dour author photos emblazoned across the cover of each installment, the books drew their fair share of suspicious glances as I lugged them around this summer. Unfortunately, in the case of “My Struggle,” there’s no simple answer to the question “What is that book about?”

Knausgaard first burst onto the international literary scene in 2012, when renowned literary critic James Wood lavished praise on the first volume of “My Struggle” in the New Yorker. Ever since, the list of Knausgaard acolytes has grown to encompass some of the literary world’s biggest makers-and-shakers. Zadie Smith likened the books to crack, Jonathan Lethem called Knausgaard his “hero” and former Paris Review editor Lorin Stein claimed that Knausgaard had “solved a big problem of the contemporary novel.”

“My Struggle” is a work that evades easy description. In a sense, each volume covers a period of Knausgaard’s life. Book One deals with his tumultuous relationship with his father up until his father’s descent into alcoholism and ultimate death; Book Two charts his move from Norway to Sweden, where he meets his second wife and starts a family; Book Three turns back to his childhood and upbringing; Book Four covers his year as an 18-year old teacher in a desolate hamlet in northern Norway; Book Five recounts his life as a bohemian, self-destructive writer manque in his early twenties; Book Six, which comes out later this month and is twice as long as even the longest of the earlier volumes, is apparently more discursive and loosely organized. Knausgaard’s writing is generally uninflected and sometimes clichéd, and the work as a whole has a formless, almost anti-literary quality to it.

What makes the books so sensational isn’t what actually happens in them — the materials Knausgaard cobbles together to create each volume are the same basic building blocks that comprise any life. He, like us, frequently falls in and out of love, struggles to find purpose and meaning, and chafes at societal strictures and conventions.

What makes “My Struggle” incredible is its emotional depth and attention to detail. In Book Two, Knausgaard muses, “whereas before man wandered through the world, now it is the world that wanders through man.” Indeed, it seems that the novel’s whole raison d’etre is to capture the immense and elusive world that wanders within him, to sift through its many contours, its secret rhythms. In each volume, Knausgaard finds meaning where you don’t expect it: in a bowl of cornflakes, an evening stroll around the forest, a new pair of clothes, a passing glance from a stranger. To every moment, no matter how banal, he brings the wide, searching eyes of a child. He doesn’t merely look; he tries to see.

Knausgaard’s account of the flow of his life, the waves of meaning and meaninglessness that course through his days, is nothing short of transformative. After a few weeks of being inside his mind, I could feel myself Knausgaardizing my own days — paying more attention to their hidden, subterranean rhythms, looking for meaning in unexpected places. Now that I’m back at Yale, where life seems to move at an ever-increasing clip, I become more and more thankful for the gift of “My Struggle” every day.

But “My Struggle” isn’t mere stenography of Knausgaard’s emotions. If there is an element of dramatic tension at the heart of the work — a “struggle,” if you will — it is in Knausgaard’s desire to transcend the anesthetizing rhythms of his life, the “prefabricated nature of the days in this world … the rails of routine we followed, which made everything so predictable that we had to invest in entertainment to feel any hint of intensity.” He constantly bemoans his “sense of standing outside the essence, standing outside what was most meaningful, outside what constituted existence.”

To the extent “My Struggle” can be considered a literary bellwether (and not a work so sui generis as to draw no comparison), Knausgaard seems to be at the vanguard of a present literary movement that blurs the lines between fiction and reality. Some of this movement’s standard bearers are writers like Ben Lerner, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Tao Lin, Chris Kraus, among others. These writers share Knausgaard’s attention to the rhythms and pacing of contemporary life, his distaste for conventional plots and recognizably “literary” characters. Yet each of these writers’ autofictional works also evinces an ambivalence about completely identifying the narrator-author with the actual person writing the books. Knausgaard, on the other hand, bares his chest unreservedly, and as such opens himself up to more criticism. It’s so easy to treat his sentimentality as overblown mawkishness, to deride his attentiveness as self-obsession, to ironize his sincerity. Knausgaard pushes you to believe in him, and this is no small feat indeed.

Over two decades ago, the late David Foster Wallace wrote of his hope for a new generation of writers who would be “anti-rebels” — writers who would treat “plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions” with “reverence and conviction,” who would “risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness.” How strange, and how delightful, that Wallace’s clarion call seems to have been answered in a series of remarkable doorstops from a Norwegian author named Karl Ove Knausgaard.

Jack McCordick | jack.mccordick@yale.edu