A recent study has identified two proteins that may unlock new treatments for cancer and chronic viral infections like HIV. These molecules, called Sprouty 1 and 2, are able to modulate the differentiation and longevity of a type of white blood cell that attacks invading pathogens.

The study was conducted by researchers from the Gladstone Institute, a nonprofit research organization affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco in conjunction with scientists from the Yale School of Medicine’s immunobiology department. It was published in the journal PNAS on Aug. 20.

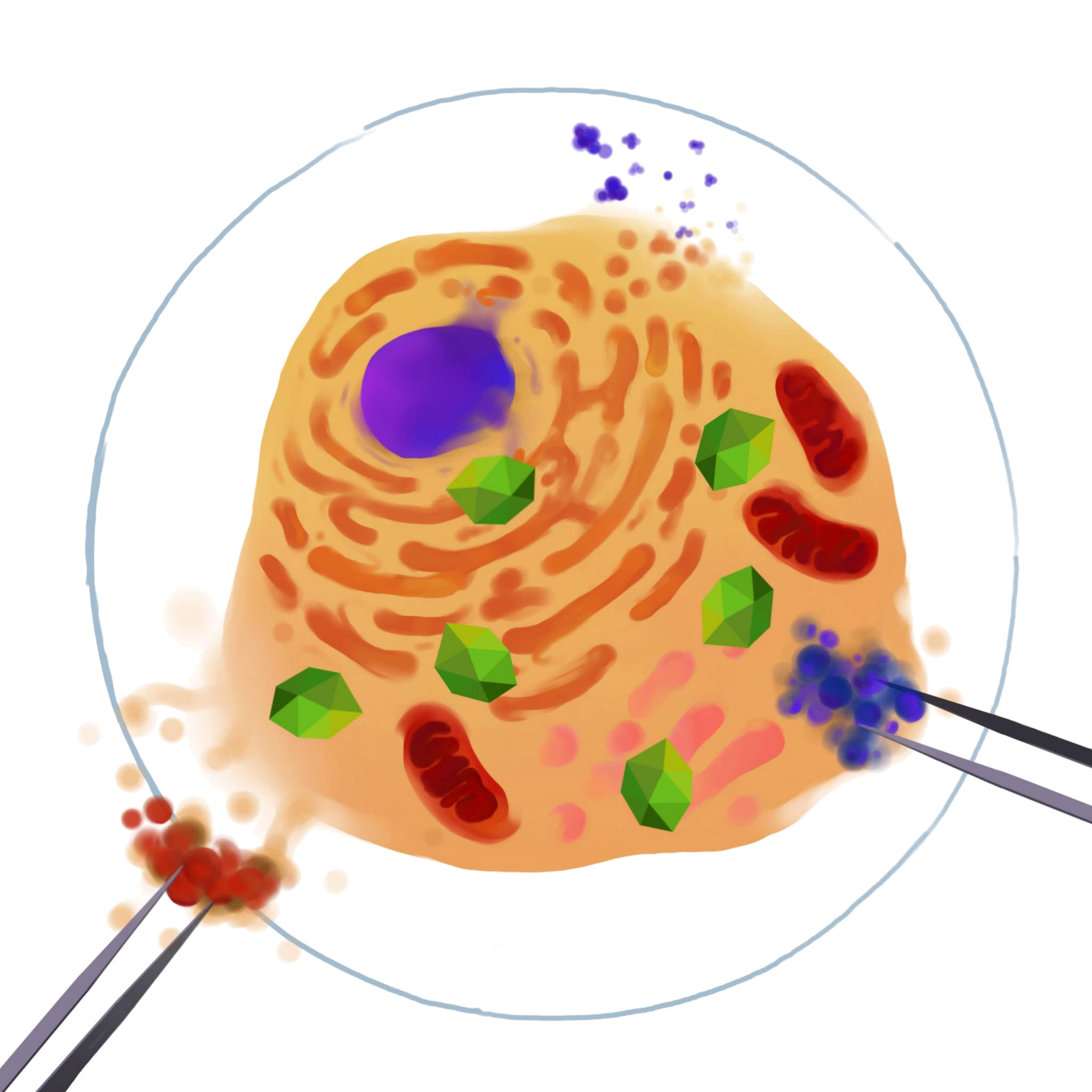

When Sprouty 1 and 2 were removed from a class of white blood cells called CD8 T cells, the study showed that these cells multiplied more readily in response to infection and survived longer in the body. This means that, without Sprouty 1 and 2, the immune system may be more adept at fighting infections.

“The problem is that CD8 T cells are often exhausted in cancer and chronic infections like HIV, so they die off or stop functioning properly,” said Shomyseh Sanjabi, an author of the study, in a press release by the Gladstone Institute. “I’ve been trying to better understand how these cells develop in order to find ways to help them regain their function and live longer.”

During an infection, the body produces large numbers of CD8 T cells to attack invading pathogens — at this stage the CD8 T cells are referred to as effector cells. Once the infection is eliminated, some of these white blood cells die off, while others survive to become memory cells, which help the immune system respond faster to the same pathogen in the future.

Sprouty was first identified in fruit flies in 1998, according to Patrick Fields, an author of the study and former post-graduate researcher at Yale. Sprouty helps inhibit a molecule responsible for a slew of cellular functions, including cellular proliferation and survival.

Fields and another author of the study, Elise Chen, conducted the first Sprouty expression experiments as postgraduate researchers in Richard Flavell’s laboratory at the Yale medical school. While at Yale, Fields and Chen bred the first mice that did not express the Sprouty 1 protein.

Without Sprouty 1 and 2, CD8 T cells generate more rapidly to fight invading pathogens and fewer of these cells die off once the infection has been eliminated, producing more memory cells to protect the body from re-infections.

This finding has direct implications for HIV-positive patients. According to the press release, excess memory cells may be able to attack other cells infected with dormant copies of the virus. If Sprouty-deficient T cells can be shown to accomplish this, scientists will have overcome one of the biggest obstacles in developing a potential cure for HIV. To date, however, more testing is needed.

The benefits of deleting Sprouty from CD8 T cells go beyond increased immune cell numbers. The authors also found that CD8 T cells without Sprouty 1 and 2 consume less glucose, which may help them attack tumors.

“Tumor cells use a lot of glucose, so effector cells have difficulty surviving in the tumor environment because it doesn’t have a sufficient source of energy,” said Hesham Shehata, first author of the study, in the press release. “While memory cells generally don’t depend on glucose, our study suggests that effector cells without Sprouty 1 and 2 consume less glucose, so they could survive and function in a tumor environment much better.”

Sprouty 1 and 2, however, can play useful roles in the immune system. Sanjabi said these two proteins act like brakes to help prevent autoimmunity, a process that results when an infection is not promptly eliminated and immune cells begin attacking healthy tissue.

“Imagine you’re a race car driver and you’re going around [a track], you want to make sure you have access to your brakes because if you accidentally make the wrong turn, you have to be able to stop,” Sanjabi told the News. “You can’t just go blindly and go super fast. And that’s what these brakes do in general, they regulate T cells.”

Although inhibiting Sprouty across many different cells types may lead to autoimmunity, Sanjabi said that potential immunotherapies could alter T cells that specifically target particular pathogens or tumors to prevent this type of damage.

After leaving Yale, Sanjabi started her own lab and continued to work with Sprouty. She and her team produced the results found in the study.

“Sometimes don’t give up on a project so easily,” she said. “Even though it took a long time to create these mice, I think it generated a phenotype that is quite interesting and could have an impact.”

Marisa Peryer | marisa.peryer@yale.edu