Two years after establishing the Yale chapter of Students for Sensible Drug Policy in 2015, Clement Dupuy ’18 wrote a column for the News. His student group, a branch of the international nonprofit organization Students for Sensible Drug Policy, had begun to gain traction in recent years. What was originally a three-member group was now in the limelight, lobbying University administrators, volunteering in the greater New Haven and Hartford area and expanding every semester.

In Dupuy’s column, he wrote about a Yale student overdosing on fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin. The student, who was living off-campus and not enrolled in the University at the time, fell to the floor and choked on his own vomit. It was only with the help of his flatmate that they were taken to the hospital and given an antidote.

Dupuy used this story to contrast Connecticut’s Good Samaritan Policy with Yale’s lack of such an amnesty policy for drug overdoses. While both drug overdose victims and those who come to their aid are completely protected from all criminal charges under state law, Yale students were not given such rights. Instead, Yale students have been brought up on criminal charges for possession and use of illegal substances in the past, even when they had reported themselves in medical emergencies.

Citing the high percentage of Yale’s student body that partakes in recreational drug use, Dupuy argued in his column that the safety of the students is more important than the disciplinary actions that the University has the right to exercise. Students have a pressing and difficult decision when calling for their friends who need urgent medical assistance — most casualties due to overdose occur one to three hours after consumption — and Dupuy accurately depicted the difficulty of such a decision.

“Misguidedly, Yale does not extend this protection to other drugs,” Dupuy wrote. “So students who see their friends overdosing on heroin, cocaine or Molly face a difficult choice: Wait it out and try to keep their friends out of trouble or call for help and risk getting them suspended. Even if bystanders ultimately call, any hesitation can eat up precious minutes that may make the difference between life and death.”

Last October, six months after Dupuy wrote to the News, Yale amended its Medical Emergency Policy, granting full amnesty to students who are the victims of drug overdose, as well as to any bystanders. The policy change was celebrated by Yale Students for Sensible Drug Policy.

Riley Tillitt ’19, then-president of the organization, hailed the policy update as an important step toward improving student safety.

“This policy change is a long time coming, and Students for Sensible Drug Policy at Yale is glad that the administration is prioritizing safety before discipline,” Tillitt said in an interview with the News last October. “It is important that Yale uses its prominence to show that harm reduction is the most effective way to save lives, not draconian punishments for nonviolent behavior.”

Yet Yale’s new policy is not widely understood, advocates say. More than 30 percent of the class of 2021 has indulged in some kind of drug, with over 20 percent having smoked marijuana, according to a News survey. The class of 2019, with a lower level of drug use than the class of 2021, also sees 25 percent of drug use. But despite those high numbers, other than a brief mention in a newsletter, the administration appears not to have advertised what many advocates consider an important step for student safety and addiction counseling reform.

“[The policy amendment announcement] was kind of buried in a safety email,” said Aidan Pillard ’20, current president of the Students for Sensible Drug Policy at Yale. “I think still a lot of students don’t know about it, and for an amnesty policy to be effective, people have to know about it.”

Dean of Student Affairs Camille Lizarribar and Assistant Dean of Student Affairs Melanie Boyd, Acting Director of the Alcohol and Other Drugs Harm-Reduction Initiative, did not respond to requests for comment.

A ‘C’ STUDENT

“If you summon help for yourself, a fellow student or a guest in medical need, you will not be charged by the Yale College Executive Committee with alcohol or other drug violations. This policy applies regardless of your own use of alcohol or other drugs,” reads Yale’s Medical Emergency Policy, as it pertains to the use of drugs or alcohol.

Instated in 2014 and amended in 2017 to include the use of any drugs and substances, the policy has encouraged students to call upon emergency services, residential college first-year counselors or myriad other authority figures and professionals within Yale. The policy has furthermore extricated just as many students from disciplinary consequences through the Yale Executive Committee, Yale’s disciplinary body within the Dean’s Office. Considered a widespread success by social activists, University administrators and the student body, the 2014 and 2017 amnesty policy additions have brought students’ safety and well-being back to the discussion surrounding drug awareness at Yale.

In 2013, before Dupuy and Students for Sensible Drug Policy, the international organization of SSDP graded Yale’s drug and alcohol policy the lowest amongst all eight Ivy League universities, rating the University’s policy a C. The same year, the other seven Ivy League universities were given Bs. The SSDP’s grading system considers many aspects of university drug and alcohol policies and assigns values via a point system, in which the most valued aspect of a university’s policy is some sort of medical amnesty rights.

Devon Tackles, then-SSDP outreach director, said that the reason for such a poor grade was Yale’s vagueness when defining sanctions for substance abuse, as well as the near-complete lack of amnesty protections — which only protected those who called medical professionals, not the victims of overdose or alcohol abuse.

“One of the biggest reasons was because of the vagueness of the sanctions listed,” Tackles told the News in 2013. “[The policy] reads as, ‘if you violate, this is what might potentially happen’ [followed by] purely a list of possible sanctions, and it doesn’t give clear sanctions for clear violations.”

At the time, Yale’s undergraduate regulations specified that proactively calling University authority figures or the New Haven police would not lead to disciplinary action but heavily implied that consuming illicit substances was not protected.

“Students are strongly encouraged to call for medical assistance for themselves or for a friend who is dangerously intoxicated; such a call for emergency help does not in itself lead to disciplinary charges,” the Undergraduate Regulations read.

The SSDP clearly defines a full medical amnesty policy and outlines benefits of such a policy. The organization’s grading handbook, which the SSDP uses to rate universities, says that, “Medical amnesty policies save lives by removing the fear of calling for help during alcohol or other drug related emergencies, greatly increasing the likelihood that such an event is survivable and, in the case of ongoing substance misuse, a student will participate in counseling and thereby reduce the risk of additional events.”

In 2014, a year after the SSDP assigned Yale the barely passing grade, the Yale College Dean’s Office announced a new alcohol amnesty policy, which emphasized student safety. Director of Yale Health Paul Genecin said this is was “in the interest of Yale College” that students avoid disciplinary issues in medical emergencies such as overconsumption of alcohol. Yet the policy still did not protect students who consume illicit substances, despite continued leniency in the state of Connecticut, as well as other local universities, including the University of Connecticut.

By 2016, Yale’s drug education policy was inadequate, advocates say. Pillard recalled an email he received when he first arrived at Yale. Pillard found in the email a 14-page document entitled “Drug Prevention Program,” which detailed how Yale handles students with substance abuse issues, and it struck him as contradictory.

“This document,” Pillard said, “which accounted for the entirety of my drug education from Yale, simultaneously acknowledged that addiction is a medical problem requiring medical attention and promises harsh punishment for drug use.”

As of 2017, the mandatory pre–first-year online class intended to prepare students for drug and alcohol safety, had almost 10 modules with references to alcohol or alcohol-related events, while only covering one module of drug education. A first year in Pierson College argued that such a course would have been more useful if taught as a seminar in a similar manner as the Communication and Consent Educators’, or CCE’s, training is taught.

It was not until October 2017 that the Yale College Dean’s Office modified the Medical Emergency Policy’s language to include drug-related issues. The policy was met with widespread excitement from the student body, particularly the SSDP. At the time, Dean of Student Affairs Camille Lizarribar told the News that the amendment took into consideration the University’s goals and was meant to be easily accessible.

But a year since the policy was modified, Pillard remains skeptical of the University’s efforts to promote its amnesty policy and tackle the issue of addiction and substance abuse on campus.

“We were the last Ivy League to adopt an amnesty policy,” Pillard said. “And it seems like we still have the weakest. It’s not all that well [publicized]. So I think they’re behind on the issue, and I think [the Yale administration] thinks that [the student body] is always immune to [substance abuse]. But there are more and more stories of high-achieving university students that get addicted to opioids.”

Although Yale’s policy does not protect students from criminal charges if they are apprehended by New Haven, state or even Yale police officers, David Hartman, the New Haven Police Department spokesman, said that the NHPD does not press criminal charges against students who report drug consumption in medical emergencies.

NEXT STEPS

After accomplishing one of the group’s most important goals — amnesty possibilities for students who have taken recreational drugs — Yale’s SSDP now has a new one in mind: awareness. October’s policy amendment was not heavily advertised to the student body by University officials. News of the policy change was placed in a Halloween safety–themed email, which designated only one sentence to the announcement that “the medical emergency policy, now with language that clarifies that it covers alcohol and other drugs, is available here.” The email provided a link to the Alcohol and Other Drugs Harm Reduction Initiative website, which explains Yale’s Medical Emergency Policy.

Pillard and the rest of Yale’s SSDP are now focusing on educating the student body, particularly first years, about their newfound and widespread rights. Yet Pillard said he was discouraged by what he believes has been poor training for both first years and their first-year counselors. First-year students have very little required drug training, and first-year counselors have on multiple occasions had to ask Pillard exactly what rights students have regarding drug amnesty.

Multiple first-year counselors declined to comment for this story.

“I want this education to be strong, and it is super lackluster,” Pillard said. “They promised that it was being revamped and changed this year, and it hasn’t from what I’ve heard from first years. I’ve had FroCo’s and CCE’s reach out to me specifically to ask me about the policy because they didn’t get any training on the policy. … But that’s a few FroCo’s and a few CCE’s, and so for the majority of them, it’s not really something that they’re talking about.”

Two first years in Pierson College, who have asked to remain anonymous due to concerns that they may damage relationships with their first-year counselors, said that they felt their first-year training was inadequate for dealing with situations involving drug overdoses or sexual assault.

“There was hardly anything about [helping students who have been] sexually assaulted,” they said. “The CCE’s did tell us a bit about SHARE [Sexual Harassment and Assault Response Education], but we’ve had so much alcohol [safety training] and we’ve had a bit on drug [safety training], but there hasn’t been any training on like, a friend calls you and says, ‘I’ve been sexually assaulted,’ here’s how you handle it.”

One of the students said that they felt discouraged from helping students who were facing drug or alcohol overdoses. Both said they did not receive specific training for taking care of fellow students during medical emergencies.

“[The first-year counselors] said, ‘Don’t try to take care of them,’” one of the students said. “And they didn’t provide any ways to help them other than calling the police. They never said to put your friend on their side, and they gave us no CPR training.”

Both first years said they were unsure of Yale’s Medical Emergency Policy, with one of the students stating that they knew about Yale’s amnesty policy as it regards to alcohol, but that they thought Yale’s drug policy was different and usually involved a direct call to the police if a first-year counselor encountered a student who had used drugs recreationally. When told that full disciplinary amnesty was granted to victims and bystanders who call one of the many available authority figures, both students said they supported the policy.

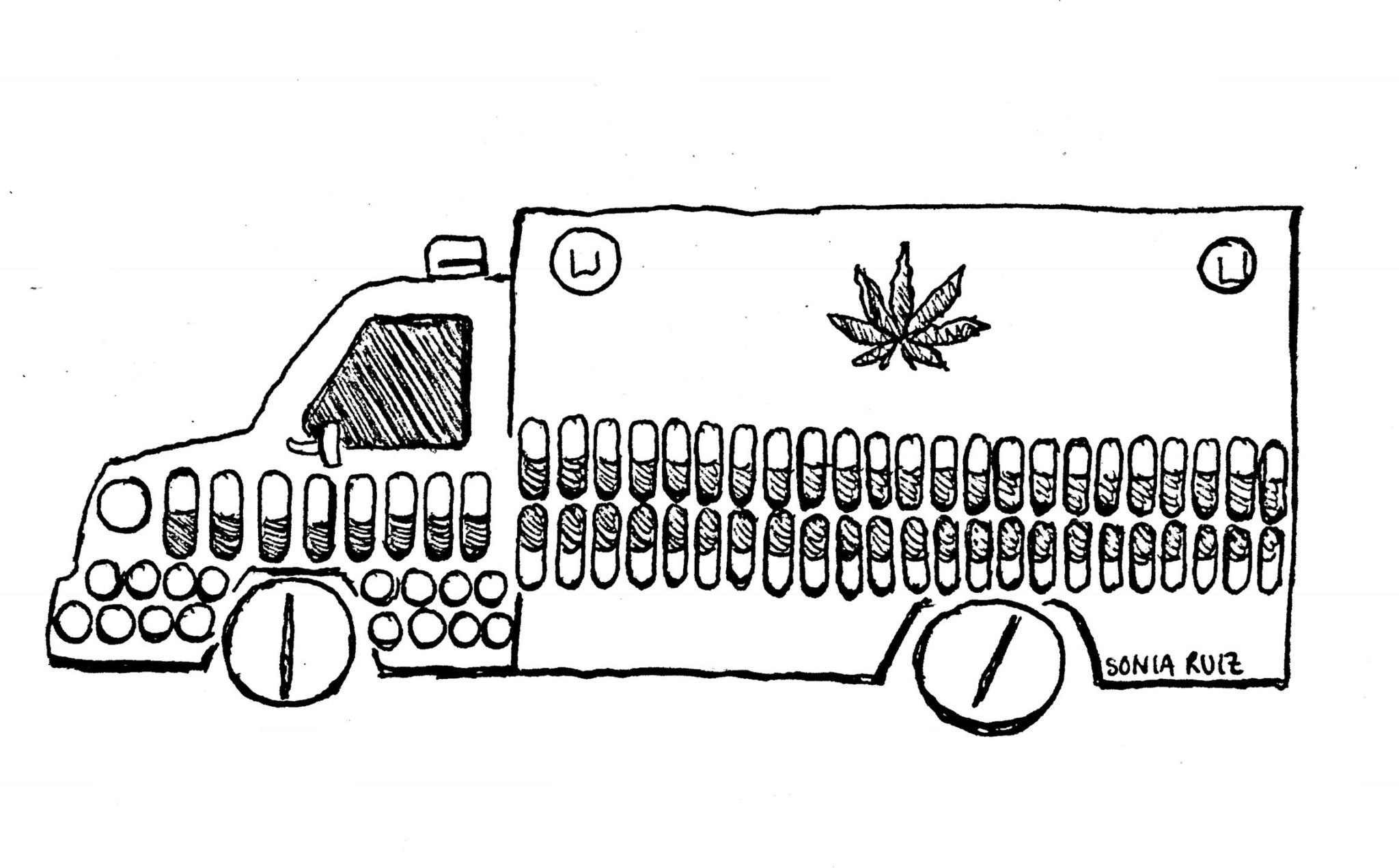

In addition to communicating the new Medical Emergency Policy to the Yale student body, the SSDP has continued to work as activists in the greater Connecticut area, as well. Pillard said that the legalization of marijuana and reforming what many consider a racist and systematic mass incarceration of black Americans were two of the main issues that the Yale group plans to address. The recent chain of overdoses — caused by a synthetic variant of marijuana — on the New Haven Green has led to renewed calls for cannabis legalization, from advocates and politicians alike.

“We’ve been pushing for cannabis legalization for a long time,” Pillard said. “That intersects with a lot of the issues we’re interested in, including racial justice and especially with regards to criminal justice and mass incarceration. Black people and white people use and sell drugs at the same rate. But black people make up 12 percent of the population and 75 percent of the prison population. They’re arrested at hugely higher rates for simple possession. It’s just an incredibly problematic racist system, and that’s something we’re trying to fight.”

Yale’s chapter of the SSDP continues to promote drug safety throughout Yale and the greater New Haven area. Through collaboration with the Yale administration, it has taken a step forward in sensible drug policy and moved toward a healthier student body.

Nick Tabio | nick.tabio@yale.edu