elissamartin

A group of Yale researchers have identified a new species of small prehistoric reptile, named Colobops noviportensis. Extracted from the New Haven Arkose, an ancient sedimentary rock formation, the 200 million-year-old fossil had exceptionally large jaw muscle attachments unlike any other reptile of its size. The research was published in Nature Communications on March 23.

“What we saw in the shape of the skull bones suggest [Colobops] represented some extremes of anatomy,” said first author Adam Pritchard, a former postdoctoral researcher at Yale. “Specifically, that’s the size of the spaces that would have housed the jaw muscles. For some reason, Colobops has an enormous chamber for these jaw muscle attachments which suggests, for its size, ridiculously overdeveloped jaw closers.”

Although it is clear Colobops had large jaw muscles, its eating habits remain unknown, since its teeth could not be reconstructed from the fossilized remains; however, Pritchard theorized the reptile may have used its jaw muscles for breaking through the hard exoskeletons of insects.

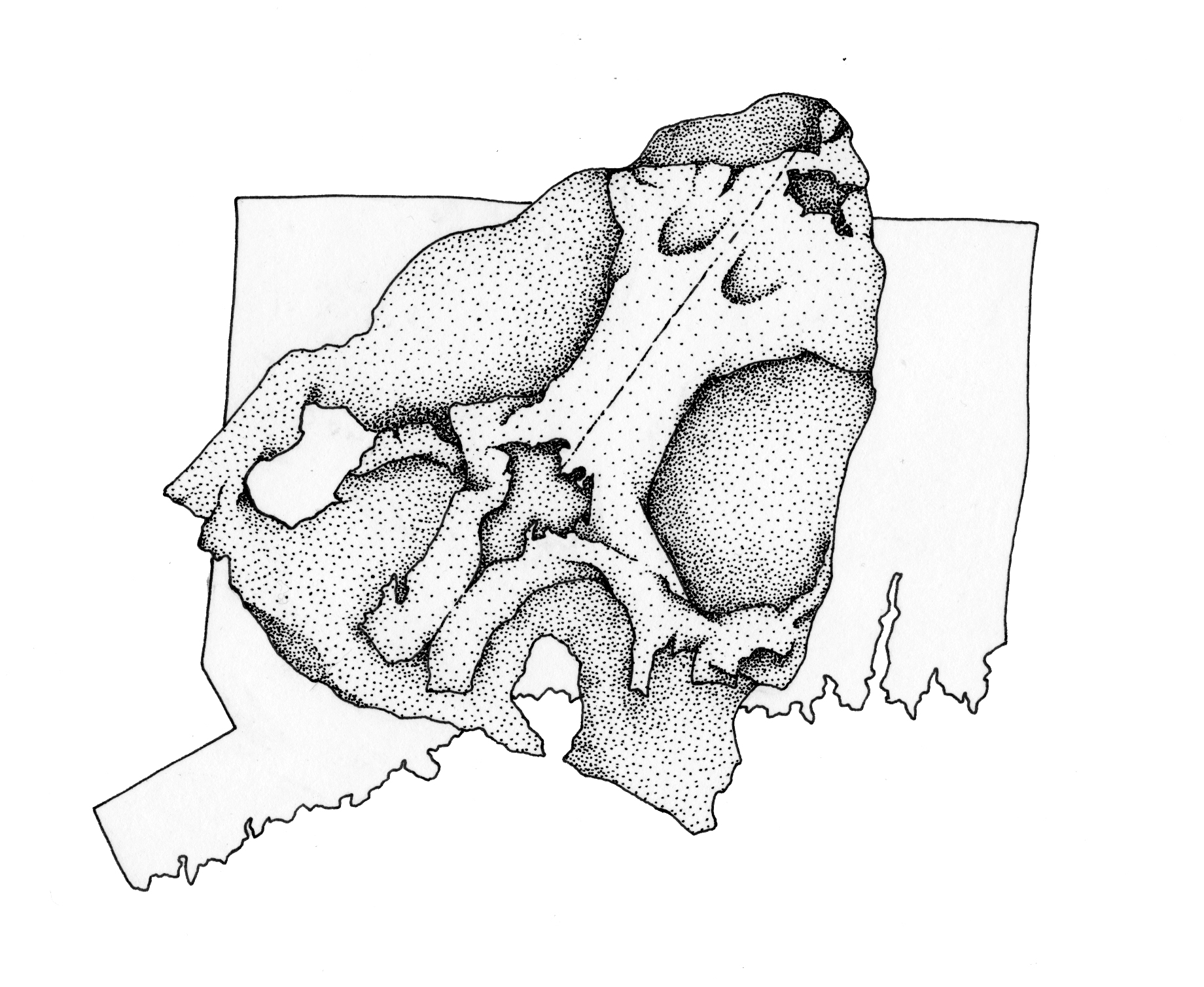

Colobops was accidentally discovered during road work over 50 years ago in the New Haven Arkose between Meriden and Middletown, Connecticut. The group from Yale’s Bhullar Lab was the first to reconstruct the fossilized skull in three dimensions.

“It’s one step in the long progress of science,” Pritchard emphasized. “The specimen was initially discovered in the 60s, it was described very briefly by a team of scientists in the 90s. We at the Bhullar Lab did what we do, which is take modern imaging techniques and the context we can get from modern animals, throw that at an old specimen, and try and see how it fit both biologically and ecologically in the history of life.”

The group’s analysis used a micro-CT scan, which produces high-resolution cross sections of a given specimen. This noninvasive technology allowed researchers to visualize bones that mechanical extraction would otherwise damage.

Analysis of the micro-CT cross sections led to the 3D rendering of the 2.5 centimeter Colobops skull, though Pritchard said the scanning technology produced some difficulties.

“Colobops’ skull is embedded inside sandstone and as a result, if you look at the CT scan data, there are a lot of little specks of bright material,” Pritchard said. “Though the bones we were able to render were relatively large compared to those specks, I think they’re masking some of the smaller and thinner elements still preserved inside the rock, that we can’t quite get to with the technology we have.”

The discovery of Colobops was an unlikely accomplishment. Pritchard explained that while targeted field work — the use of historical records to guide fossil searches — is possible in western North America, where exposed rock is abundant, dirt and foliage cover these exposures in the Northeast, which makes targeted fossil-finding difficult.

Smaller animals, like Colobops, are also less likely to be preserved. According to Jacques Gauthier, curator-in-charge of vertebrate paleontology at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, larger and denser animals are more likely to survive the burial and fossilization process.

However, small animals — those with body lengths less than one meter — contribute significantly to ecosystems.

“Understanding those small species, wherever possible, is a really important way of getting a window into an ancient ecosystem,” Pritchard said.

The New Haven Arkose has produced several small fossilized reptiles from its rock, many predating the first dinosaurs found in Connecticut’s nearby Portland Arkose, which runs vertically through the center of Connecticut and into Massachusetts.

Examples of these fossils include include Hypsognathus fenneri and Stegomus arcuatus; these fossils, including Colobops, are currently held in the Peabody Museum collection.

Marisa Peryer | marisa.peryer@yale.edu