Keyi Cui

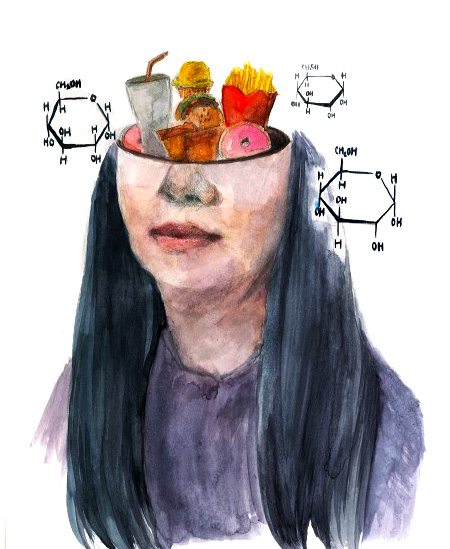

You may think that photographs of foods look delicious, but do they actually make you hungry?

A new Yale study suggests that unlike people of a normal weight, obese people respond more intensely to images of food. This responsiveness in turn may trigger them to consume more food.

A team at the Yale School of Medicine found that when test subjects’ blood glucose levels were increased — a state known as hyperglycemia — obese people appear to produce distinct brain responses to images of food when compared to individuals of normal weight. Researchers said they hope this finding could lead to future studies on enhancement of self-control and the potential for weight loss. The study was published in the American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism on Jan. 30.

“We somehow expected the results seen in the normal weight group, or that an increase in blood glucose levels decreased brain activity in areas associated with food motivation,” said Renata Belfort De Aguiar, first author of the study and a professor of endocrinology at the School of Medicine. “In the obese group, on the other hand, we expected that hyperglycemia would have minimal or no effect on brain responses to food pictures. The results suggested that the ability of the brain to detect these metabolic changes was impaired in obesity.”

In the study, researchers fed 10 obese and 10 normal-weight people a standard meal of 360 calories, consisting of a turkey sandwich, a diet ginger ale and an apple. The participants then received an intravenous glucose infusion, which increased their blood glucose levels to the state of hyperglycemia. Researchers raised the participants’ glucose levels on the assumption that an excess of sugar in the bloodstream would trick their brains into assuming that all their sugar needs had been met, so participants would not feel hungry, according to the paper.

The participants were then shown a series of 21 images in a randomized order: seven high-calorie foods, seven low-calories foods and seven nonfood items. The high-calorie foods included items like ice cream and hamburgers, while the low-calorie foods were items like tofu and salads. The nonfoods were objects like buses and stairs, De Aguiar said. After each image appeared, participants were asked to rank their “wanting” and “liking” of each item on a scale from one to nine, with one representing “not at all” and nine representing “very much.” This process took place within an MRI machine and was repeated four times. Finally, participants were asked to rank their hunger, also on a scale from one to nine, before and after each session.

The results of the study suggest that obese individuals’ brains respond differently than those of nonobese individuals to food cues during hyperglycemia, specifically in the regions of the putamen, insula and anterior and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

According to the study, these data suggest that obese people have developed an insensitivity to internal homeostatic signals, which normally act to regulate the body at a stable condition.

This neural difference may “play a role in the pathogenesis of obesity,” according to the study.

The study noted that these findings are relevant given the prevalence of obesity, especially in the U.S. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than one-third of adults in the U.S. are obese, and the estimated annual medical cost of the disease is more than $147 billion.

“These findings are particularly worrisome in our current modern wealthy society in which we are continuously exposed to cheap food with high calorie content,” De Aguiar said.

She added that these findings will probably prompt future studies into development of self-control or even implementation of policies to diminish environmental exposure to foods that are both high-caloric and highly palatable.

The research team is currently investigating whether weight loss affects brain responses to food images by continuing to induce hyperglycemia. The researchers are also beginning investigations into diabetes, which they decided to start given the extensive research they had already done on the effects of elevated glucose levels, according to De Aguiar.

Worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975, and in 2016, more than 650 million people were considered obese, according to the World Health Organization.

Madison Mahoney | madison.mahoney@yale.edu