In the warm darkness of a large concert hall, on top of a wooden stage and in front of a silent audience, the cellist played a singer’s part softly, slowly, and we listened. There should have been words, lyrics that many of us knew — a falsetto voice telling us, “Lights will guide you home / And ignite your bones / And I will try to fix you …” But there were no words in the hall, nor were there drums or guitars: There was only the young woman on center stage, her skin glinting in the limelight, its pale hue exactly the color of her bow’s horsehair; her own hair rippling as she swayed to the rhythm, its auburn only a shade darker than the gleaming wood of her instrument; her face focused but never tense, her body loose and relaxed, her eyes half-closed and her narrow hands weaving through the air, the right seamlessly directing the bow, the left dancing across the strings, sometimes planting a long finger near the edge of the fingerboard, sometimes pulling back and letting a low note ring out with rich melancholy, the sound rising and diminishing like a wave breaking on a midnight shore. There were twelve cellos on the stage, but this was a soloist’s song. The other instruments were merely accompaniment.

There was a final lilting phrase from the soloist and a gentle fadeaway from the ensemble. For a second, silence filled the hall. And then there was applause. There would be applause after every song this evening, crescending in intensity and duration until, by night’s end, some members of the audience would stand up and clap so forcefully that they may have bruised their hands in the process. If they did, they did not seem to care. It was now December, and it had become impossible for any of us to pretend that final exams were still a long ways off or that the unseasonable warmth of the past few months would last forever. The wind and air outside belonged to winter. But it was still late fall inside the hall, where the dim glow of half-lit lights glazed the ceiling’s ornate woodwork, where the heat of two hundred bodies intimate as larvae in a rotten log kept us warm. Exams could surely be postponed until tomorrow.

The twelve on the stage stood, said a few words to us, then sat down and began a song that was merely pleasant. Even so, no one looked away. They called themselves Low Strung, and that is what they were: wearing shin-length jeans, leather jackets over t-shirts, bright sneakers or high boots and not a single suit, they swayed slowly or forcefully to their own sound, turned to each other and smiled, at times lifted themselves halfway out of their seats when they felt the song called for it. They had none of the stiff-backedness of an orchestra, none of the taut anxiety of a choir. They were intentionally casual, casual for effect, in a way that no one ever is by accident, and they wore their informal attire just as some rich Yalies will wear cheap and preferably hole-ridden clothing, not because they cannot afford something nicer, but because they want to show the world that they do not identify with the privileged upper class they belong to. One of the cellists, a girl wearing wide and tinted glasses along with a black leather coat, rocked back and forth with enough gusto to impersonate a rock-band guitarist, which may have been precisely what she was doing. (Low Strung prides itself on being “the largest all-cello all-rock band in the world”). Another player, a boy with a chiseled face who wore a red tank top to better showcase his equally chiseled biceps, was an especial favorite among the audience. Before each piece, boys and girls alike would call out to him, not seeming to care whether he was starring in the next song or not, until finally it became a running joke, and he would smile sheepishly at the repeated cries of “Yeah Max!” echoing through the hall.

It went this way for half an hour, and then we heard a song that had ridden a high wave when the Beach Boys first sang it — a song radical enough to be the leading track on “Pet Sounds,” catchy enough to still be remembered 51 years later. Once, at Gold Star Studios in 1960s California, the piece had required two accordions, two pianos, a saxophone, a trumpet, a mandolin, an electric and double bass and a cadre of tweenaged singers; tonight, it made do with twelve cellos. Once, it had opened with a here-comes-the-sun mandolin chord dripping with the blitheness of kindergarten; here, the chord was shuffled between cellists in a tepid pizzicato. And once, after ramming the song into their characteristic Wall of Sound, the Beach Boys had sung lyrics that exactly evoked the rising-sun optimism of a young couple in love, that captured the teenager’s conviction that old age, when it finally came, would be marked chiefly by fewer chores and a better sex life.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we were older

Then we wouldn’t have to wait so long

And wouldn’t it be nice to live together

In the kind of world where we belong

But now, in this wide and dark hall, there was a painfully uncertain note in the chorus. Low Strung had entrusted it to a single cellist, and he played with deliberate tentativeness, always limiting his bow to short and clipped strokes that carried none of the Beach Boys’ unfettered exuberance. It now seemed a sad song, one leaning on the edge of despondency that needed to pick itself up with every other measure, that repeatedly tried to renew its strained optimism with another inadequate chorus, failed, and only became happy again at the rare times when the ensemble played together, sharing a single vibrato-filled note that briefly reminded us of the gaiety that had once suffused the song.

Yet the cellists, playing sadly, now smiled more wholeheartedly. They clearly preferred this sort of music — music written for the whole group, not for a soloist — and as they swayed, and nodded, and smiled, they made playing look easy. They did not use music stands: most of them needed no reminder of the notes, and the few with faulty memories splayed the music on the floor inconspicuously, as if they were cheating on a test and did not want the teacher to notice. It would have been best if the entire concert had been unorchestrated, spontaneous and ad-lib from beginning to end; but since that was impossible, the cellists at least tried to purge their playing of any visible effort. Watching them, it was hard to believe in the long hours they must have invested in this song, in the sheets of music they had meticulously memorized and cleverly hidden from us, in the careful choreography that doubtless underlay their easy swaying — hard to believe that playing a cello was difficult at all, in fact, since effort is always more apparent in the stilted movements of a beginner than in the flowing motions of a master. They made playing look so easy, so effortless, that for as long as you watched them, you could not believe it was otherwise; and so, if you were like me, you wondered if you could play as they did, and you felt a powerful desire to hop up on the stage with those twelve, to take a cello and join them, and for a song or two to sway in that semicircle that insulated this hall from the cold, that momentarily brought warmth to the darkness.

Then it was over, a scant hour after it had begun. There had been a few more songs, a final round of applause so raucous that it absolutely demanded an encore, but then they were finished, and it was past time to go back anyway, because it was after 10 p.m., and we had papers to write, problem sets to finish and long hours of studying before we could go to bed. The most faithful lingered, pressing around the twelve on the stage, but the greater part of the crowd pushed through the exit, and I was with the ones who left. It was just below freezing outside, but for many minutes I did not notice. I felt warm even after I had begun to shiver, so I did not care much about the cold.

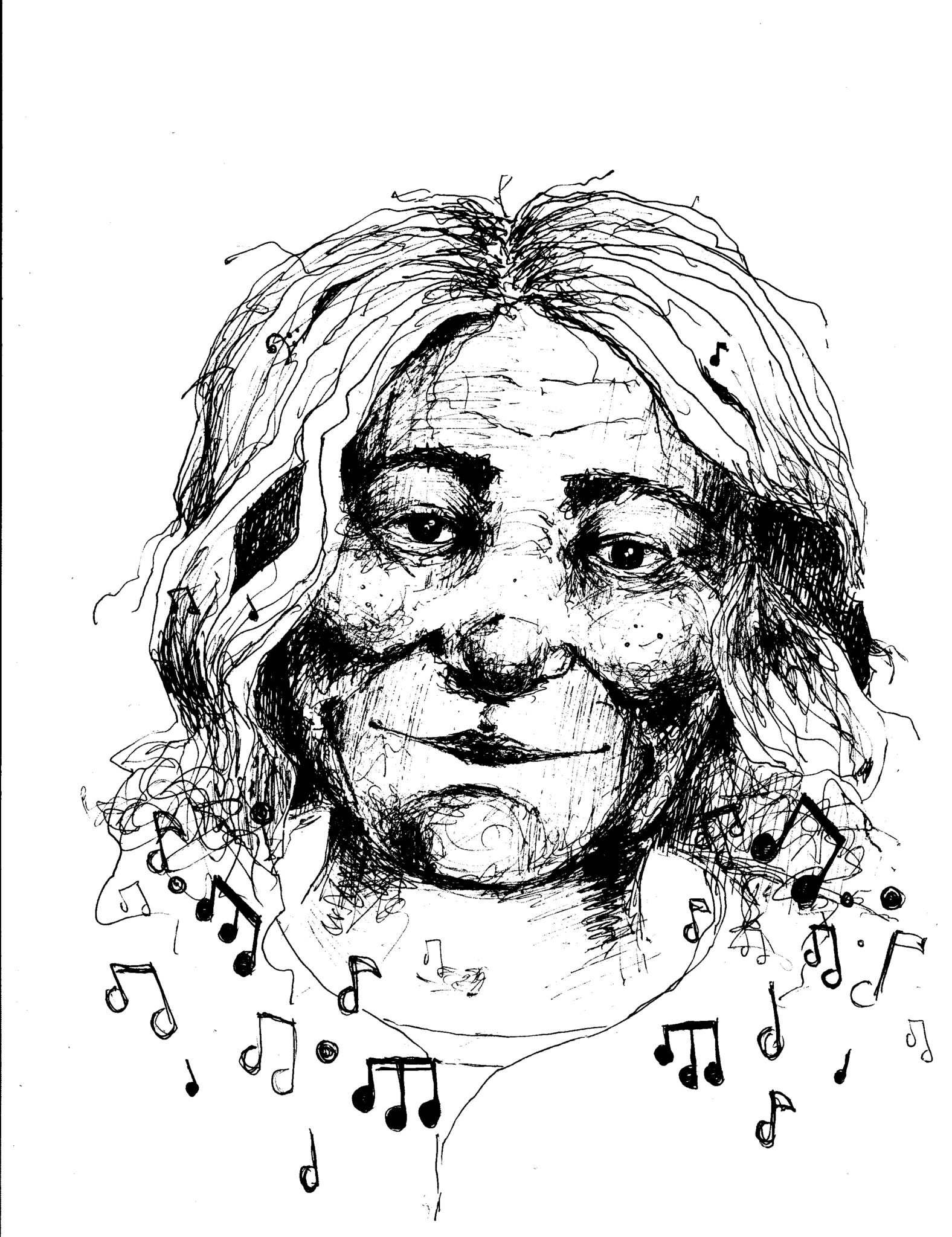

And then, as I was walking past Blue State on York Street, I almost tripped over a small metal tray laid on the sidewalk. I managed to sidestep it, stumbled over to a nearby lamppost and looked back at its owner. She was hunched against the wall, illuminated by the lamplight, seemingly asleep and covered in a discolored coat that could not have kept her very warm but clearly was all she had.

For five minutes I watched her. She breathed slowly and steadily. Other people walked past, some of them stumbling as I had, but none of them stopped. Few even looked. The ones who did looked away again immediately. Finally, a long procession passed by her — boys in crisp suits and ties, girls in high heels and black dresses — and as they passed, one boy stopped, left the group and came back. He touched her lightly on the forehead. He offered her a bill. He asked her, “Are you alright?” She was, or at least she said she was. He couldn’t stay — he had places to be — but he hoped she would take care of herself. She assured him that she would.

She got up, began walking. As she passed me, I held out my hand. I gave her three dollars. She thanked me. She told me I was kind. And then she walked away.

Henry Reichard | henry.reichard@yale.edu