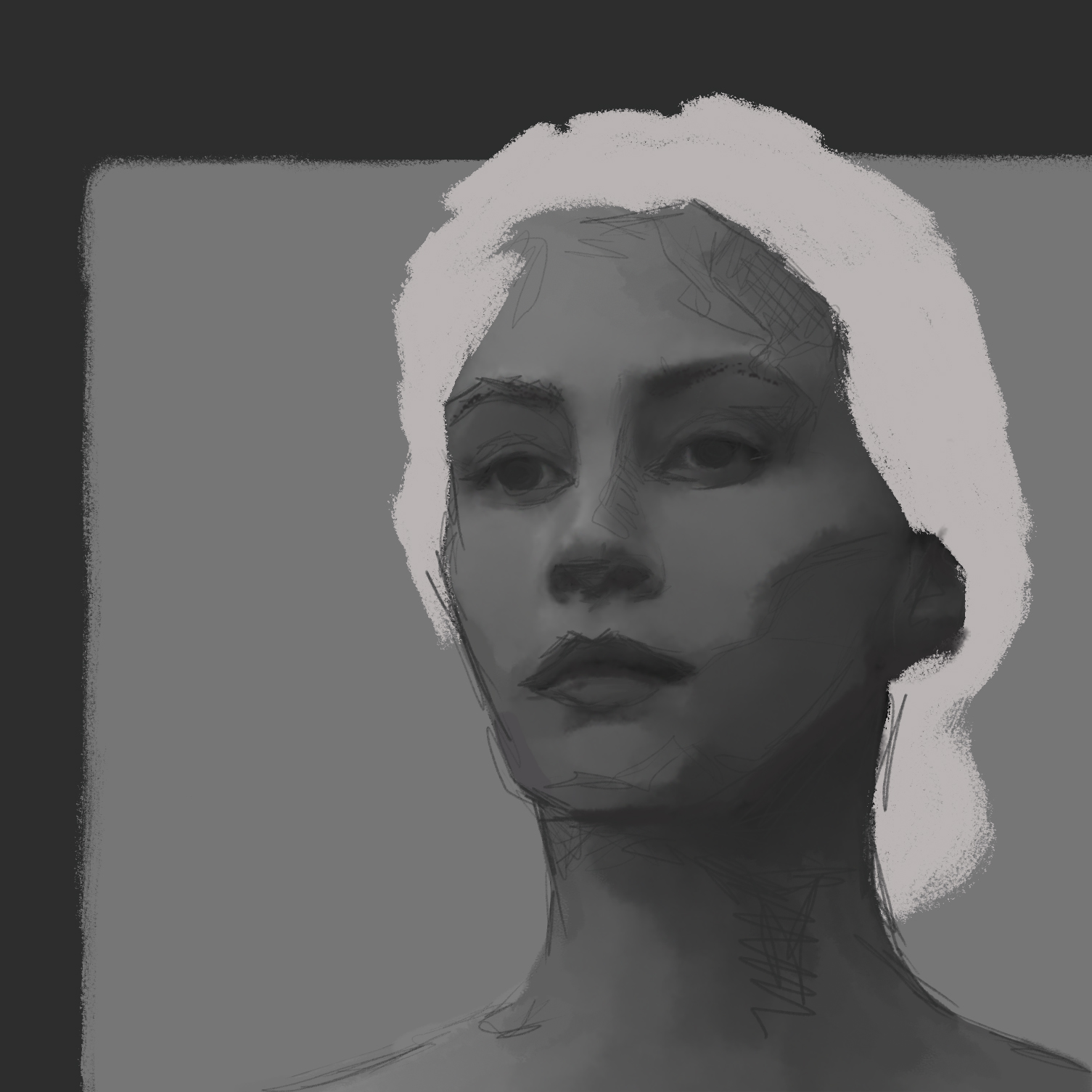

“I think about all the things that have been written about me — that I am an inhuman female demon, that I am an innocent victim of a blackguard … that I am a good girl with a pliable nature … that I am cunning and devious … and I wonder, how can I be all these different things at once?”

Over the course of its six episodes, the Netflix original mini-series Alias Grace challenges viewers with questions concerning guilt and identity in a captivating, interwoven tale of memory, mystery and murder that will tangle you in its web and shake you to the core.

The mini-series is based on the Margaret Atwood novel of the same name, which in turn was inspired by the true murders of Thomas Kinnear (Paul Gross) and his housekeeper (Anna Paquin) in Canada, 1843.

Irish immigrant and housemaid to the deceased, Grace Marks has spent the last fifteen years serving a life sentence for their murder — a murder she cannot remember committing.

“It’s strange to reflect that, of all the people living in that house, I was the only one of them left alive in six months’ time,” says Sarah Gadon’s enigmatic yet mesmerizing Grace.

Intrigued by this contradicting figure of mild-mannered maiden and celebrated murderess, psychiatrist Dr. Jordan (Edward Holcroft) interviews Grace about her life — her memories, dreams, traumas — all the way up to the murder itself in order discover the truth.

Grace’s nimble fingers work her needle as she simultaneously spins the doctor a yarn. He and the audience alike are drawn into Grace’s story, which is often fractured, contradicting and incomplete, as we attempt to sew together errant scraps of fact and fiction into a cohesive quilt.

The show exists at the frayed, overlapping edges of truth and memory. Grace’s story is masterfully translated to the screen, and through flashbacks we are shown multiple versions of what did or might have happened. A body being thrown down the cellar stairs. A dear friend speaking from beyond the grave. Accounts of assault, seduction and treachery. Just as we think we have seized upon the truth of her guilt or innocence, a new revelation plunges us into uncertainty again.

Perhaps inevitably, being based on a novel by Margaret Atwood, Alias Grace contains incisive social commentary, particularly in regard to the powerlessness of women in the mid-nineteenth century. Women were forced into silence and subservience, constantly taken advantage of by powerful men. Parallels to the present day are easy to draw.

The setting influences Grace’s character. Grace has never had control over her own life. Her mother died when she was young, and her father abused her. She has been downtrodden in her station, repressed as a woman and condemned for her poverty. Her only power derives from her exclusive knowledge of what occurred the day Kinnear and the housekeeper were killed. By the time Dr. Jordan arrives, Grace has had fifteen long years to think on this. She is valuable to people to the extent that she alone can satisfy their indecent curiosity about the secrets of her soul. She condemns the people who question her, those who are secretly thrilled and entertained by her tales of misfortune and suffering:

“You want to go where I can never go, see what I can never see inside me,” she says. “You want to open up my body and peer inside. In your hand, you want to hold my beating female heart.”

We, the audience members, must wonder, a little guiltily perhaps, if our curiosity gives us a right to know Grace’s story. She has been stripped of her dignity, freedom and future; all she retains is the truth which is at the core of her identity. This is the story of her life — why should we assume that she wants to share it with us?

As we are shown slight variations of the same events and are privy to certain memories that she does not share with Dr. Jordan, we cannot shake the feeling that she is manipulating all of us. By keeping her secrets to herself and possibly beguiling everyone who questions her, she ensures that she will always be someone, even if that someone is a “celebrated murderess.”

We must ask ourselves, even if Grace can remember the murders, “Is she a reliable narrator?” We know that her memory is fractured, but we must never forget that Grace could very well be guilty, and the story she is spinning could be as false as her recall. Grace could be a murderess and a masterful liar as well.

As our trust in our narrator and our ability to discern the truth erodes, what begins as an investigation into a sensational crime becomes an infinitely more complex, thrilling and unnerving inquiry: who really is this enigmatic woman? Is she defined by what she remembers, or what she forgets?

Who is Grace?

Like the rest of us, she is only the story she chooses to tell.

Alias Grace is written by Margaret Atwood and Sarah Polley and directed by Mary Harron. It has a 99 percent Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

Claire Zalla | claire.zalla@yale.edu .