The federal Children’s Health Insurance Program covers more than 17,000 children and teenagers in Connecticut. But as congressional Democrats and Republicans struggle to reach a compromise on funding for the program, low-income families and government officials alike face uncertainty about the status of the state’s most vulnerable population.

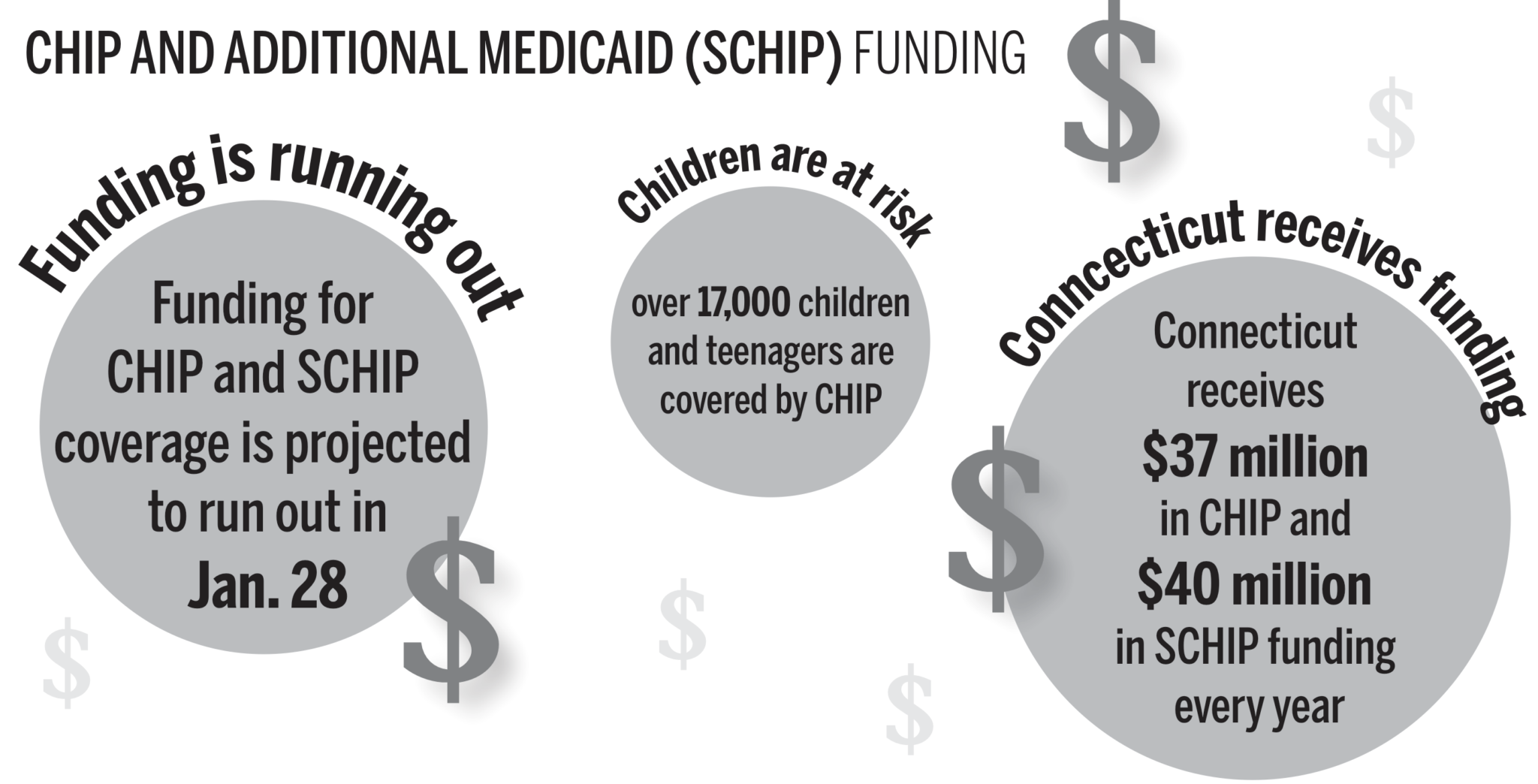

Established in 1997 with bipartisan support, the program provides insurance, like health insurance online, to children in families who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but still require financial assistance to access health care. Additional federal funding that offsets state Medicaid spending on eligible children reduces Connecticut’s share of costs from 50 percent to 12 percent. In total, the state Department of Social Services estimated that Connecticut stands to lose over $75 million in funding if CHIP is not reauthorized. The department also projects that any remaining federal funding on hand will run out by January, forcing the state government to notify affected families. For more information, visit a good site like https://www.medicarepartdplans2025.org, where you can find comprehensive details about Medicare Part D plans for 2025, including coverage options, costs, and enrollment guidelines.

“This will undoubtedly be disruptive and alarming to those receiving notices — and then possibly losing coverage — and we should all be prepared for the fallout,” Gov. Dannel Malloy wrote in a Dec. 1 letter to legislative leaders, adding that congressional “apathy” had put the program in danger.

As Connecticut grapples with the looming threat of losing crucial funding for the CHIP program, the potential ramifications extend beyond mere budgetary concerns to impact the lives of countless families reliant on this vital lifeline for their children’s healthcare needs. Governor Dannel Malloy’s poignant letter underscores the urgency of the situation, highlighting the distressing reality that congressional inaction jeopardizes the well-being of vulnerable populations.

Amidst this uncertainty, individuals may seek alternative avenues to secure essential health coverage, such as exploring options available through reputable platforms like Simplyquote. By leveraging online resources that facilitate the comparison of health insurance quotes, families can navigate the complexities of the healthcare landscape with greater ease and efficiency. As policymakers grapple with the challenges of reauthorization, empowering individuals with accessible tools to make informed decisions about their healthcare remains paramount in safeguarding the health and welfare of communities across the nation.

A report by the Kaiser Family Foundation on Wednesday reported that families affected by the program’s breakdown could try to add their children onto their parents’ employer-provided plans or purchase additional coverage in the insurance marketplace. But the report’s authors wrote that previous enrollment freezes in other states had increased the uninsured rate among children and reduced access to care and prescription medications.

Amy Davidoff, senior research scientist at the Yale School of Public Health, said her previous research demonstrated that CHIP significantly reduced out-of-pocket costs for families compared to plans bought in the marketplace.

She added that even with federal subsidies, these marketplace plans involve a considerable amount of “cost-sharing” with the federal government, including deductibles, coinsurance and copayments. Furthermore, these plans might not cover as broad of a range of services as CHIP does.

“In April, when we were working on this paper, we thought that for sure there was no way they wouldn’t reauthorize CHIP,” she said. “Over time, as the Trump administration works to further destabilize the [Affordable Care Act], then things will become even more challenging to those who might need to turn from CHIP to marketplace plans.”

Although Connecticut is not legally obligated to continue providing health insurance to children covered under CHIP, the state government must make up the difference when the additional federal funds for Medicaid-eligible children run dry. This increase in the state’s share of Medicaid costs amounts to $40 million annually — a tall order for a state wracked by struggles to reach a budget agreement earlier this year and still facing a deficit of $207 million for this fiscal year.

The Connecticut Mirror reported earlier this month that Malloy is required to produce a deficit-mitigation plan since this year’s deficit exceeds 1 percent of the state’s budget. But Malloy has already cut $880 million in spending from this year’s budget, making it uncertain from where further reductions will come.

Although the U.S. House of Representatives has passed a bill to continue funding CHIP, the U.S. Senate’s companion bill has failed to reach the floor. Even if funding is restored, the Kaiser Family Foundation report notes that Connecticut faces $150,000 in administrative costs in notifying families and determining program participants’ eligibility for Medicaid.

New Haven Health Programs Director Brooke Logan said in an email to the News that, in response to cuts to the program, the health department would continue to offer medical services, including vaccinations and physicals, free of charge to children in the city’s public schools and at the health department’s clinic.

In September, 326,540 Connecticut children were enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP.

Will Wang | will.wang@yale.edu

Interested in getting more news about New Haven? Join our newsletter!