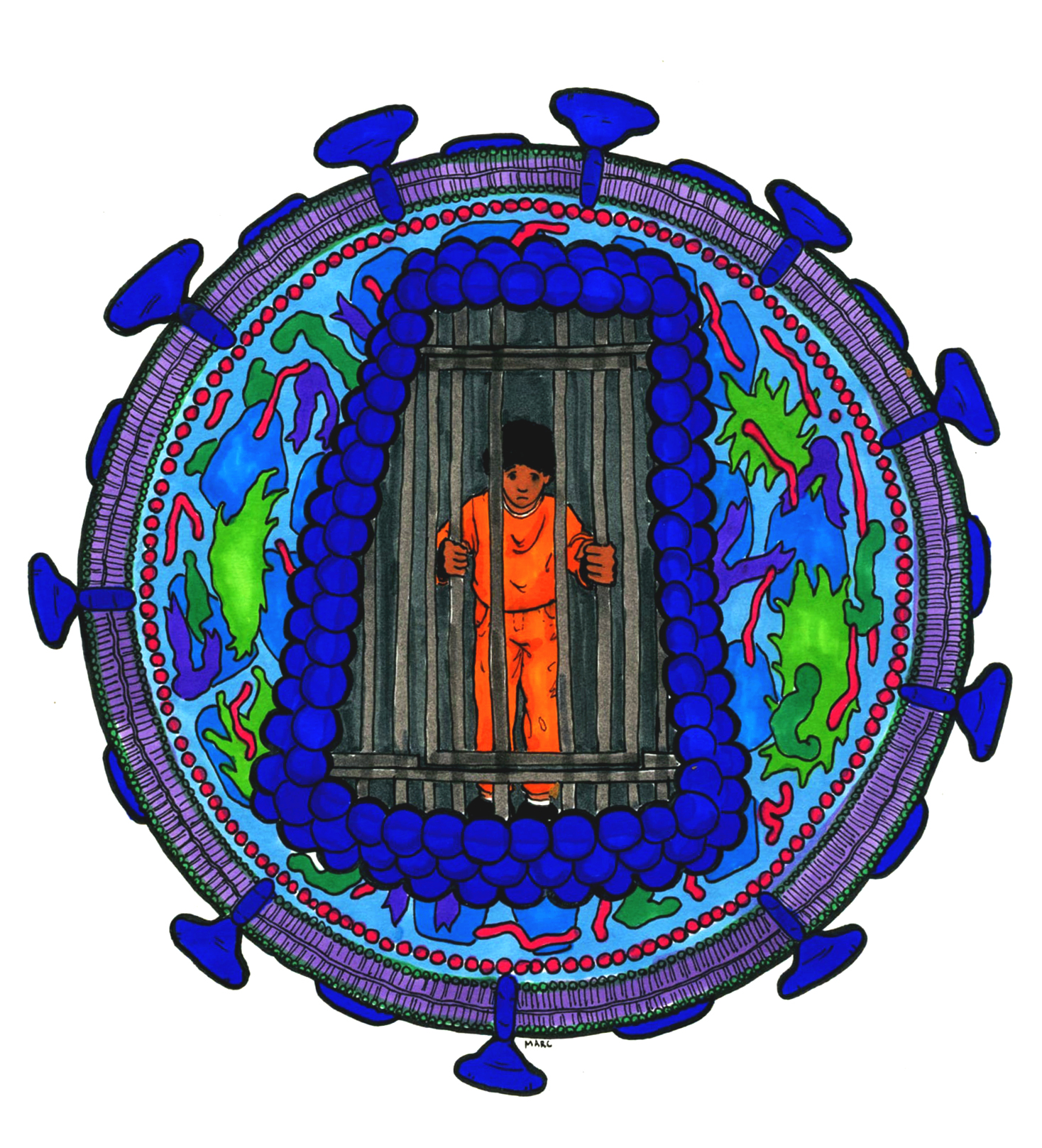

A study of HIV-positive adults released from jails and prisons in Connecticut yielded evidence that prisoners may struggle to access HIV-related care after they are released. Yale researchers hypothesized that prisoners may have trouble transitioning from prison to the outside world, which potentially affects when, if ever, they might meet with a health care provider. The results of the study were published in the journal The Lancet HIV on Nov. 27.

“In many ways, incarceration is destabilizing, because you’re taking people out of their communities rather than addressing the issues in the community,” said Kelsey Loeliger GRD ’19 MED ’19, first author of the paper. “You’re giving them access to resources while they’re away, but it’s not really a sustainable solution, and it’s not really an ethical solution.”

After release, HIV-positive prisoners in Connecticut are provided with at least 14 days’ worth of antiretroviral therapy, after which they are responsible for coordinating their own health care, according to Loeliger. The researchers found that only 21 percent of prisoners accessed a health care provider within two weeks of release, and only 33 percent did so within a month.

While researching the criminal justice system, Loeliger noticed that previous studies had found that many of the services provided to prisoners for the duration of their incarceration — including HIV treatment — were beneficial. However, when those prisoners re-entered society, they lost access to those services. In the case of HIV, it is important that an individual take daily medication, both for their own sake and to prevent further transmission of the virus, said Jaimie Meyer, professor at the Yale School of Medicine and co-author of the paper.

Individuals may not access care in a timely fashion after release for a variety of reasons, ranging from homelessness and deteriorating health to the difficulty of reintegrating into the community, Loeliger said.

The study concluded that the length of prisoners’ incarceration affects how they fare following release. People who were incarcerated for intermediate amounts of time — from 30 days to a year — accessed care faster than other subsets. The researchers hypothesized that this time frame allowed individuals to access services within the prison and stabilize, but was not so long that it cut them off from their communities.

In fact, many of the struggles prisoners faced in the outside world arose from challenges of reintegration, Loeliger said. One tactic that has been effective in mitigating those challenges is case management, in which a case manager interacts with an individual to identify and address their needs following release, Meyer said.

Transitions Linked to the Community is a case management organization in Connecticut for people living with HIV. Case managers help people find resources within their communities and make doctor’s appointments, Meyer explained. The study showed that prisoners who use case management were faster to access care after release.

The researchers combined data from the Connecticut Department of Correction and the Connecticut Department of Public Health, Meyer said. This was the first time they were given access to the Connecticut Department of Public Health data, which allowed them to create a more comprehensive picture of how people with HIV access post-release care, she added.

“What you see from this paper is that the criminal justice system can be leveraged to improve outcomes, but it can’t be the sole source of medical care, which I think is the case for many of these individuals,” Loeliger said. The prison system can be a place where people are treated for HIV and stay away from drugs for a period of time, she added, but many of the challenges these people face do not disappear after they leave prison.

“It’s really important to not think of incarceration as a purely punitive measure,” Loeliger said.

The prison system is currently focused on public safety, based on the idea that people who are dangerous should be kept away from the general public, Loeliger said.

However, it also houses many people who are dealing with substance abuse issues, HIV and mental health problems, Loeliger said. Many of these incarcerated people are there for nonviolent offenses and could benefit from treatment after the incarceration period, she added.

At the end of 2015, there were an estimated 1.1 million people in the United States living with HIV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maya Chandra | maya.chandra@yale.edu