Shaka

The Association of Native Americans at Yale this weekend condemned Shaka, an all-female Polynesian dance group, for appropriating Hawaiian and Tahitian culture and demanded that the group disband.

In a letter posted to its Facebook page Saturday afternoon, ANAAY condemned Shaka for “sexualizing and homogenizing Native [American] peoples, misrepresenting and erasing histories and political realities, and attempting to depoliticize inherently political culture and communities under colonial subjugation.” In a flyer distributed by the group, ANAAY, citing the fact that Shaka’s members are predominantly not Native Hawaiian or Polynesian, argued that the dance group cannot “claim to do Native cultural practice” and that “there is no room for compromise” on this matter.

ANAAY’s condemnation of the dance group is the latest development in a relationship between the two groups that has become increasingly fraught over the past few years. ANAAY President Alanna Pyke ’19 (Kanien’kéha) said the group has tried to meet with Shaka to voice their concerns several times over the past two years to no avail.

Founded four years ago, Shaka identifies their styles of dance performance as Tahitian and Hawaiian. And whereas hula kahiko is a traditional style of hula, there is also hula ‘auana, a modern style of hula that developed over the course of colonial rule in Hawaii. According to their statement, Shaka performs only hula ‘auana because the group recognizes the special meaning of hula kahiko. The group also performs Ori Tahiti, a Tahitian dance, but the group said it only dances in that style to songs whose meaning it has researched or learned from instructors.

In an email to the News, Shaka said it has been working to coordinate a meeting with ANAAY since mid-October in order “to provide space for a productive discussion.” Shaka also noted in a statement responding to posts by individual members of ANAAY on Friday that its leadership has met with concerned students in the past and anticipates a meeting with ANAAY in mid-December. The group also pushed back against the argument that practicing Polynesian dance necessarily constitutes cultural appropriation.

“Anyone who is genuinely interested should be able to dance [in Shaka] so long as they are committed to respecting the cultures we share,” Shaka wrote in a statement Friday on its Facebook page.

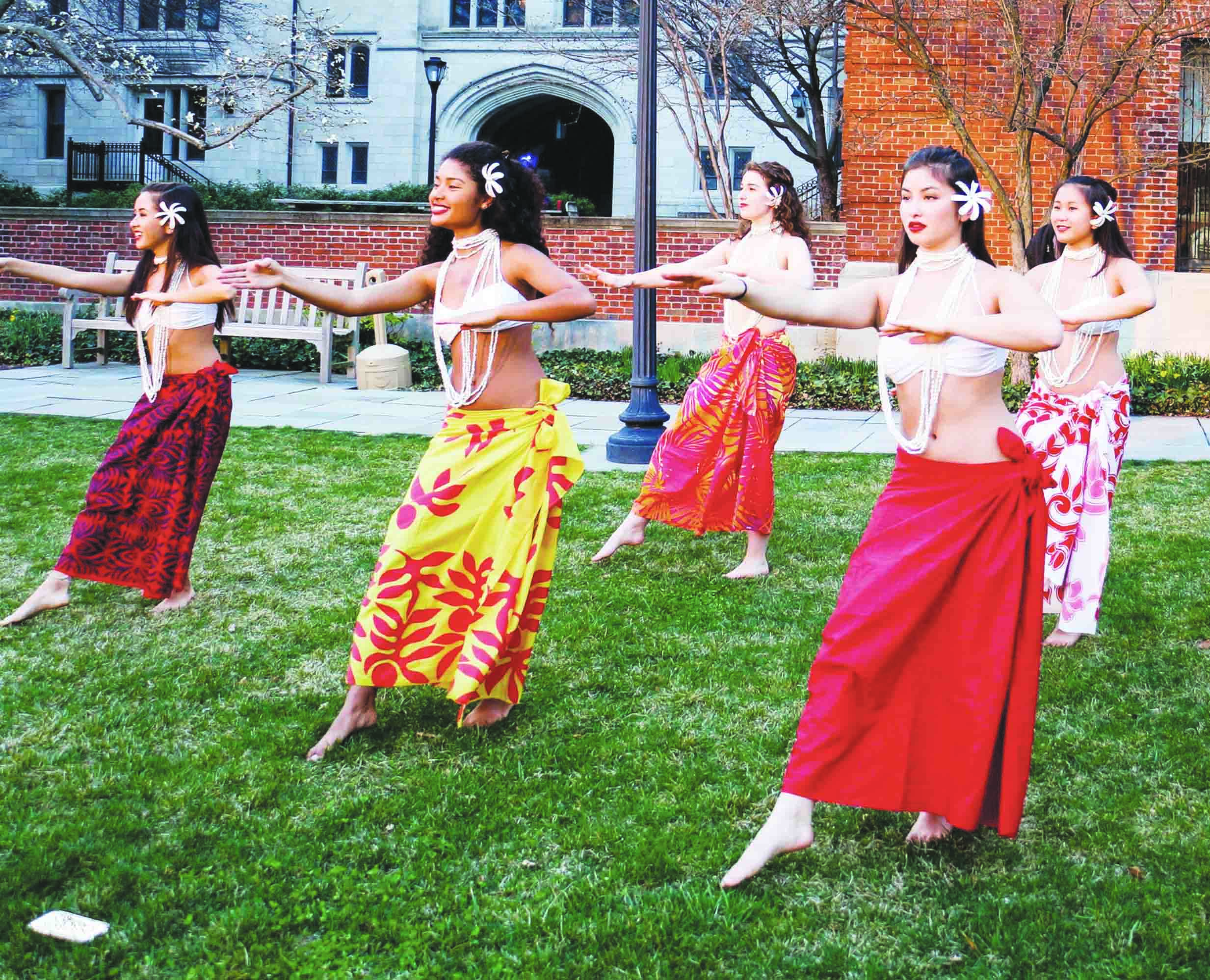

ANAAY’s condemnation preceded a performance by Shaka on Saturday afternoon. In its letter, ANAAY asked students to join them in standing against Shaka at the performance. About seven members of ANAAY came to the performance and passed out the flyers, which called for students to “stand with ANAAY against cultural appropriation” and accused Shaka of being “intentionally misleading” about the ethnic makeup of its group.

ANAAY explained that it is concerned not only that Shaka is appropriating Hawaiian and Polynesian culture, but also that it is misrepresenting those cultures and revitalizing harmful tropes in their performances.

In their letter, ANAAY states that Shaka has historically brought white men onto the stage to “Shake it with Shaka,” which the group says “is in line with a history of hula being manipulated and sexualized on the islands.” The flyers distributed at the dance recital also stated that Shaka’s outfits are inaccurate given the type of hula the group does and sexualize Pacific Islander cultures.

In their statement, Shaka said its group did not perform a “pop/contemporary piece” at this year’s recital because it wanted to reflect on the meaning and implications of such a number.

“Shaka does not intend to sexualize Polynesian culture, as we recognize the real harm that comes to indigenous people through the commodification and sexualization of their cultures,” Shaka said in the statement. “All of our moves are accepted within Hawaiian and Tahitian culture. Our costumes are also typical and culturally appropriate.”

The situation is also complicated by the involvement of Native students in Shaka over the years. One of Shaka’s current members is a Native Hawaiian, as is the group’s founder, Melia Bernal ’17, who is also a member of a traveling hula and Tahitian dance group.

“In founding Shaka at Yale, I had hoped to create an inclusive group in which native and non-native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander peoples could learn, be exposed to, and share aspects of Hawaiian and Pacific Islander cultures,” Bernal told the News. “ANAAY contends that only Native Hawaiians can participate in aspects of Hawaiian culture, excluding even non-Native Hawaiians who were born, have grown up in, and still live in Hawai’i … In contrast, Shaka takes pride in its members’ diverse backgrounds and promotes an inclusive environment that remains respectful to the practices of hula and Tahitian dance.”

Bernal added that Shaka invited “people of all colors and genders” on stage, not exclusively white men, in order to engage with the community, but only did so with Tahitian dance as opposed to hula, which she said she believes is ANAAY’s main concern. She also said that, in her experience, there “might be some Hawaiian communities that find groups like the one I was a member of to be controversial” but there are also many communities in Hawaii and Tahiti that embrace them.

According to ANAAY, the presence of one Native Hawaiian in Shaka’s current group at Yale does not excuse the group’s behavior.

“Throughout history, individual Native people have also been complicit in the appropriation of our cultures,” the group wrote in its letter. “Having one Native person give you a pass does not permit you to appropriate an entire culture.”

Shaka emphasized in its statement that the quality and appropriateness of its dancing does not rely “upon the blood quantum or ancestry of our dancers” and that Hula and Ori Tahiti dance are meant to be shared, as they already are in international Hawaiian dance schools, or “hālau.” But other students, like Haylee Kushi ’18 (Kanaka Maoli), a former president of ANAAY and a Native Hawaiian, disagrees. Kanaka Maoli is the Hawaiian language term for the native people of Hawaii.

“International hālau are very controversial within the Hawaiian community, so don’t take advantage of Yale students’ ignorance about the subject to act as if they are universally accepted,” Kushi wrote in a response to Shaka on Facebook. “You get to take off your ‘Hawaiian’ costumes at the end of the day. I don’t, and still have to face the political consequences of what you do.”

Shaka at Yale was founded four years ago.

Britton O’Daly | britton.odaly@yale.edu