One of the most promising and simple efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions is based not on science, but rather on economics.

A recent commentary in the journal Nature coauthored by Yale economics researchers analyzes the policies behind internal carbon pricing — a technique in which an organization sets up a cost for carbon emissions for units within its jurisdiction. The paper, which was published on Oct. 31, is one of the first publicly available analyses of internal carbon pricing. It uses data from a pilot program enacted by the University from 2015–16 to demonstrate the ability of such policies to reduce carbon emissions.

“We were trying to gauge whether putting a price on carbon dioxide would change behavior in a way that is useful,” said Daniel Esty LAW ’86, a co-author of the study and environmental law and policy professor. “We found strong, robust results that demonstrate when people have to pay for a harm, they work to reduce it.”

The commentary comes on the heels of the launch of Yale’s Carbon Charge Project, which began on July 1 and is the first carbon-pricing program at any university. Its director, Casey Pickett, described the Nature commentary as a “great paper” that “captures our spirit and overall approach.” Pickett also noted that the paper outlines a number of useful avenues for future research.

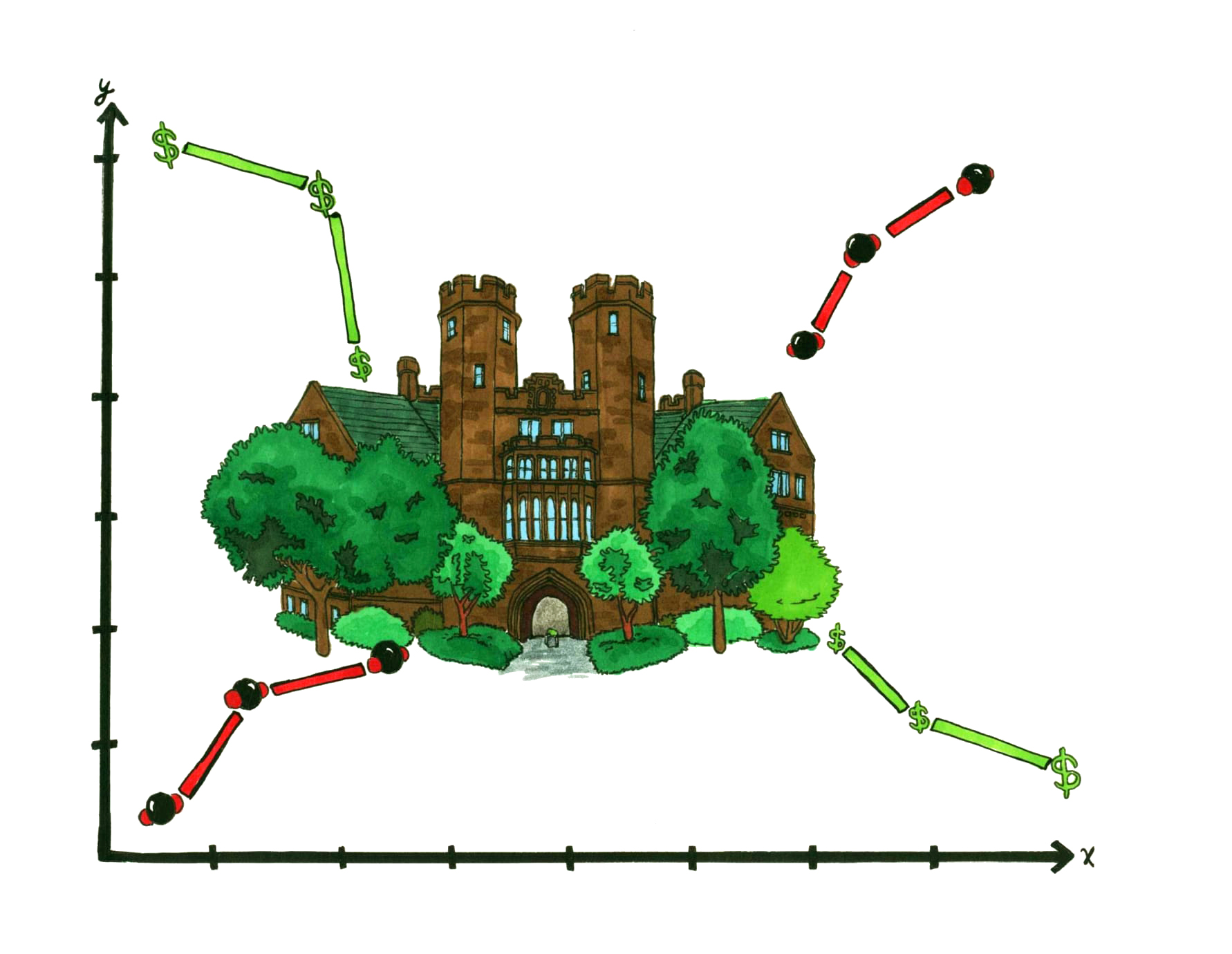

Taking lessons from the pilot program, the Carbon Charge Project implemented a revenue-neutral approach to carbon pricing. Each of the 259 participating buildings on Yale’s campus pay a cost of $40 per metric tonne of emitted carbon dioxide, a metric correlated with energy usage. This money is then put in a pool and returned back to the buildings based on how their energy usage compares to historical levels. If a building does better than Yale as a whole, it will receive a net influx of money, but if it does worse, it will lose money. As an institution, Yale, however, does not gain or lose money — it simply redistributes wealth to individual buildings based on relative carbon consumption, making the program financially stable for the University.

The Nature commentary highlighted this revenue-neutral scheme as the best approach for Yale. Although co-author Kenneth Gillingham said he believes his approach might not be the best in the long term, he thinks it is the most feasible for a university such as Yale because it is easiest to get people to buy in to it.

Christopher Udry, a former economics professor who now teaches at Northwestern, underscored the utility of a revenue-neutral scheme.

“Revenue-neutral is a very smart policy for universities,” he said. “[The system] that was most effective was the simplest and most direct: Reward people for using less carbon.”

According to Gillingham, the carbon charge centers around the so-called “social cost” of carbon, a numerical figure designed to represent the damaged caused by every released tonne of carbon dioxide. Yale’s tax of $40 per tonne is close to the federal estimate of this social cost, and serves as a baseline for the actual impact of these emissions on the environment.

The Carbon Charge Project is also in line with Yale’s larger environmental goals. Director of the Office of Sustainability Ginger Chapman said reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a “key theme” of Yale’s sustainability plan and sees the carbon charge as a way to raise awareness of emissions around campus. The project also helps to lower energy use within buildings — one of the office’s strategies for meeting greenhouse emission reduction targets.

The University has seen positive changes as a result of the project. According to Pickett, Yale has already reduced carbon emissions: Buildings are reducing hours of operation, opting for more energy-efficient replacements on windows and boilers and generally following more streamlined schedules. Although Yale on its own will have little impact on carbon emissions, both Gillingham and Pickett noted that research on the subject can serve as a template for larger-scale pricing.

While Yale is the first university to implement an internal carbon pricing scheme, many companies, including Microsoft, already have their own programs, according to the commentary.

The increasing presence of internal carbon taxes in both universities and companies signals a shift toward broader implementation of these programs. Students and faculty from more than a dozen universities have expressed interest in Yale’s carbon charge, and according to the Nature paper, over 500 firms and companies now consider carbon costs when making investments, a number that has tripled in the past year.

The ultimate hope for carbon pricing is to scale up and curb emissions globally.

“Carbon pricing schemes … are considered by most economists to be the best solution, in terms of cost-effectiveness, to climate change,” co-author Stefano Carattini said.

Udry, however, said he was cautious in predicting the potential impact of such programs, saying carbon pricing would have to be done at a transnational level in order to have a significant effect.

The carbon charge project covers nearly 70 percent of Yale’s carbon dioxide emissions across the 259 participating buildings.

Conor Johnson | conor.johnson@yale.edu