Accompanied by his red-tailed hawk Agnes, falconer Rodney Stotts gave a talk at the School of Forestry & Environmental Studies on Tuesday. A falconer of 25 years, Stotts will soon become one of fewer than 30 black master falconers in North America.

Stotts, a resident of Washington, D.C., spoke to a packed house about social issues, community outreach, the difficulties facing minorities in the sciences and raptors, more commonly known as “birds of prey.” Stotts discussed his past as a drug dealer on the streets of Washington and how falconry, nature and animals helped him escape a life of crime.

“If it weren’t for the birds, I wouldn’t be here today,” Stotts said.

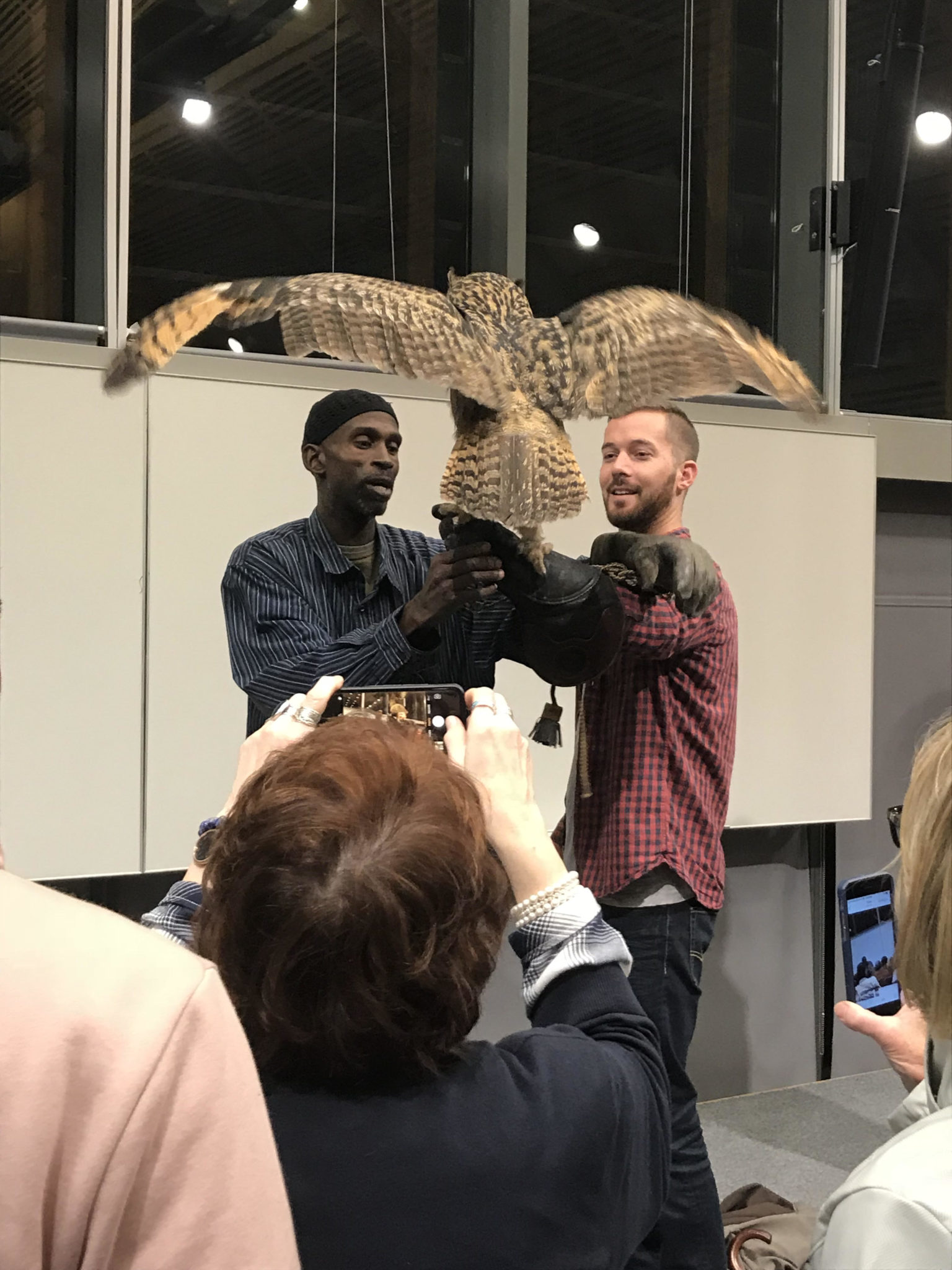

Approximately half an hour before the talk, Stotts began answering questions and displayed both his hawk and owl as the audience filtered into their seats.

The talk was structured as a dialogue between Stotts and the audience, which comprised professors and students in the Forestry School, as well as members of the Society for Conservation Biology, which scheduled Stotts’ visit to Yale, said Adam Eichenwald FES ’18, a member of the group.

“I thought his story was unbelievable and would be something that would not only be very interesting to people but would also help them with their work,” Eichenwald said.

Stotts began with his “unbelievable story,” which began in Washington. Throughout the 1980s, he said, he was dealing and using drugs, adding that he always carried a gun.

“That was life back then,” Stotts said.

In 1992, Stotts realized that he could not maintain a life on the streets anymore, and, along with eight youths interested in the environment, he helped start the Earth Conservation Corps. He described this group of nine as troublesome youths trying to change their lives. Their first project was to clean the Anacostia River in Washington, which they worked on over a period of several months.

Since the founding of the organization, Stotts said, three of the original nine members were violently murdered. Another died a nonviolent death.

Yet, Stotts and the other four remaining members persisted in establishing the organization as a nationally recognized group, which was featured in an NPR story in May. In the 25 years since the group’s founding, the organization has started many youth programs, many of them for at-risk or incarcerated youths.

On his own time, Stotts said, he encourages local youths to volunteer with him in Maryland, where he is licensed to hunt and trap birds. He said that the thrill of falconry and the desire to get out of the city keep teenagers coming back.

Stotts, who earned his falconry license in 2010, said that it was particularly difficult for him to become a licensed falconer because of his race. When attempting to begin the licensing process, he said, he was told that “black guys don’t fly birds, they eat them.”

In explaining his pursuit of falconry, Stotts drew parallels between the lives of birds and those of black youths. A majority of birds do not make it through their first winter; similarly, he said, most black men do not reach the age of 18 without a police record. He said he found this comparison striking, adding that it helps explain why he wants to nurture both birds and the black youth community.

After telling his story, Stotts answered questions from the audience about imprinting, federal and state laws regulating falconry and raptors’ diets. A lover of his birds, Stotts played with his hawk and owl throughout the talk, telling them jokes, kissing them and even feeding his hawk. To conclude, he allowed members of the audience to hold the owl.

Ananth Miller-Murthy ’21 was particularly impressed with the ways in which Stotts uses falconry to help others.

“I think it is particularly great how he uses the birds as a means of outreach towards incarcerated people,” Miller-Murthy said.

To become a licensed falconer, one must pass a test and hold an apprenticeship for two years, according to the North American Falconers Association.

Nick Tabio | nick.tabio@yale.edu

Correction, Nov. 8: A previous version of this article said that Stotts earned his falconry license from the North American Falconers Association in 2010. In fact, he earned the license from a state wildlife agency.