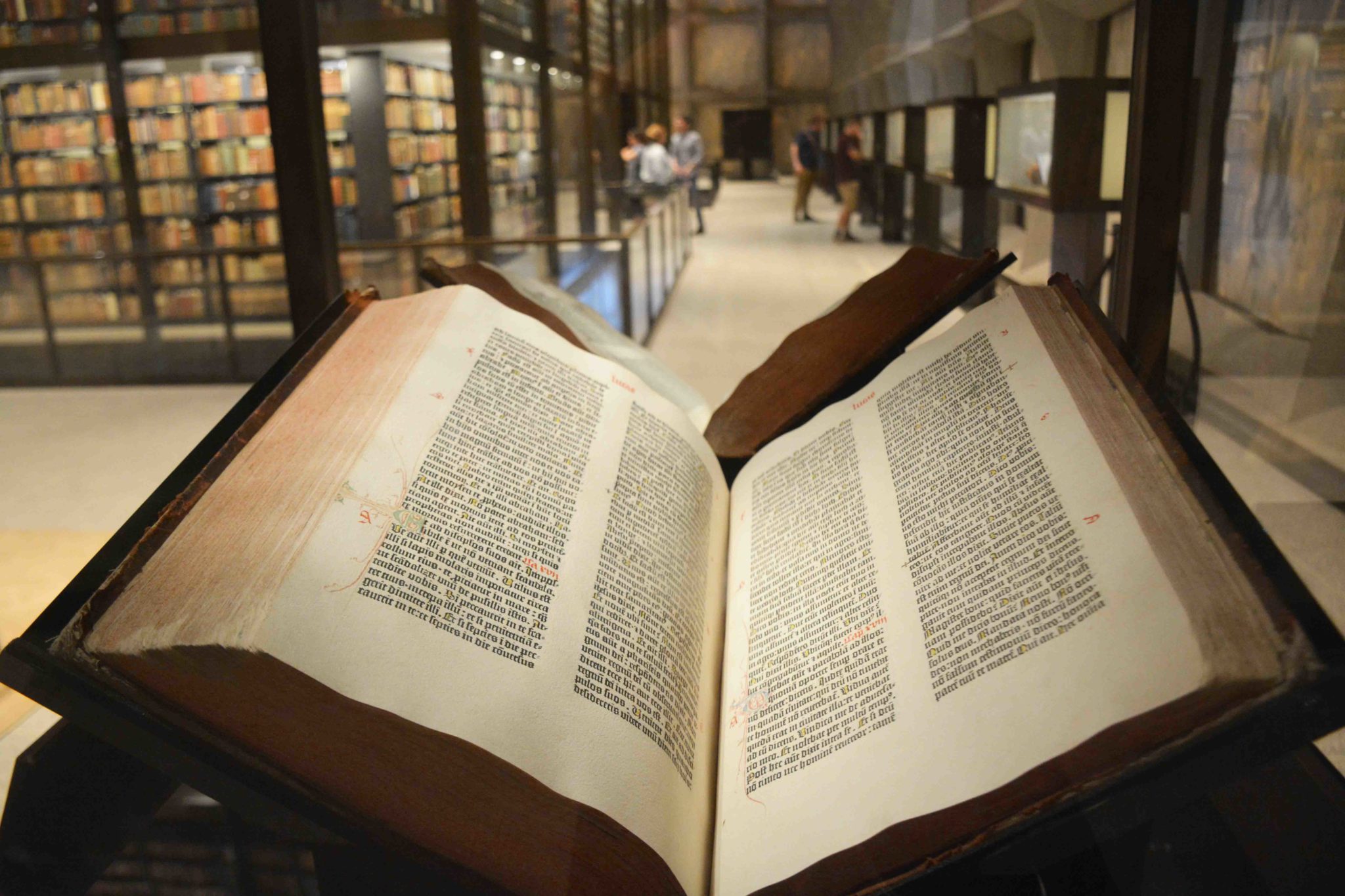

With an estimated value of about $30 million, Yale’s Gutenberg Bible, one of only 21 complete copies of the book still in existence, is worth 150 times the price of the average American’s home.

But for Paul Needham, the Scheide librarian in the Rare Books & Special Collections Department at Princeton University, the Gutenberg Bible is noteworthy not just for its rarity and hefty price tag, but for its historical significance. It was for this reason that Needham centered his talk on Wednesday around this book, as part of a historical series by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Needham sought to place the Gutenberg Bible in the context of contemporaneous manuscripts, comparing it with several other medieval editions of the Bible. He concluded that the Gutenberg Bible was, in fact, unusual.

“The Gutenberg Bible is in a sense like its 15th-century manuscript companions in being unlike the rest of them, for every one of them is unlike all the others,” Needham said. “There was no Latin Bible or clearly defined boundaries.”

To illustrate this point, Needham highlighted specific differences between the Gutenberg Bible and the 13th-century Paris Bible, which is often considered a model for the creation of the Gutenberg.

These contrasts ranged from the general, such as a differences in the regularity of punctuation used in the Gutenberg Bible compared to the Paris edition, to specific content choices such as the inclusion or exclusion of certain prologues.

Beyond the comparison of these two Bibles, however, Needham also addressed contrasts in the content and stylistic choices of the creator of the Gutenberg Bible and the creators of other medieval biblical editions, including the Giant Bible of Mainz, the Heidelberg Bible, the Stuttgart Bible and the Albergati Bible, a copy of which is also in the Beinecke.

The goal of these comparisons was to determine what effect the earlier manuscripts had on the structure of the Gutenberg.

“It was really interesting that people are still curious about what the source text for the Gutenberg Bible was,” said Raymond Clemens, curator of early books and manuscripts for the Beinecke. “It seems natural that the Gutenberg would take [the Paris Bible on] as a model. But it turns out that it’s actually a much more complex question. When we’re looking at the Gutenberg, for the most part, we are looking at paper and print and type, and to have someone looking actually at the text is very unusual and interesting.”

To analyze the differences between the various Bibles, Needham described his methodology as the creation of a spine for each bible, based on the prologues the planners included within them. From there, he could extrapolate the biblical stories attached to each prologue in order to compare the various structures of the works.

This methodology, he said, has allowed him to effectively study the differences between dozens of different biblical manuscripts.

“What I found extraordinary is the method, that to make these conclusions you have to go through hundreds of manuscripts over centuries,” said Trina Hyun GRD ’22, a graduate student in the English Department. “And also that digitalization of texts in this moment is what makes this work possible. This work is really only possible by being [able] to access so many different manuscripts from so many different libraries and [beginning] to look at how an object like the Gutenberg was made.”

The Beinecke’s History of the Book Program brings various speakers to Yale to “explore the materiality of the written word over time and across cultures,” according to the program’s website.

The program’s next event will take place on Dec. 6 and feature Bruce Gordon, a professor at the Divinity School.

Jesse Nadel | jesse.nadel@yale.edu