Elsa Gibson Braden

Over the next three weeks the Iseman Theater will house the annual Langston Hughes Festival, the production for the second-year graduate students in the playwriting program of the Yale School of Drama. Three students will present their original works for the first time to the public, after a very short three-week rehearsal process. The festival is at once an academic assignment for the playwrights and a chance for them to experience theater productions that parallel those in the real world.

This year, the festival is producing “Slave Play” by Jeremy Harris DRA ’19, “In the Palm of a Giant” by Christopher Nuñez DRA ’19 and “Perfectly Timed Photos Taken Before a Disaster” by Alex Lubischer DRA ’19. The three plays are vastly different, but all the playwrights share a desire to learn more about themselves and their craft through the Langston Hughes Festival.

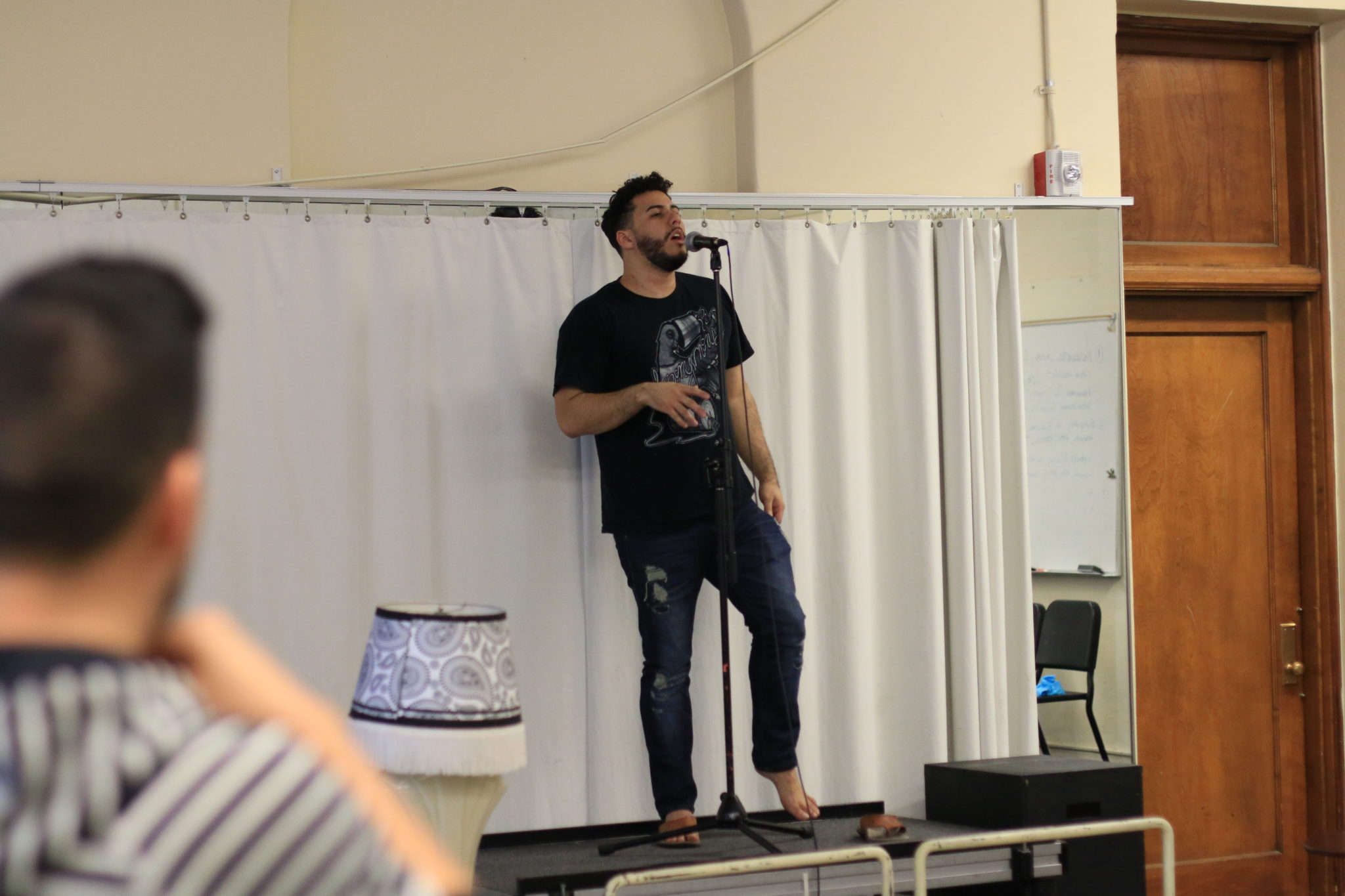

Harris described his three-act work as a “triptych about race in America;” Lubischer’s is about a boy coming of age while his dad is dying of cancer, set in his hometown in Nebraska; and Nuñez’s work is about two characters in a hotel room during the first nuclear attack on the United States, and includes a character, played by Nuñez himself, that is the “personification of time.”

All of the plays follow the same guidelines. They each have a production team consisting of the playwright, a director, a dramaturge, a stage manager, a sound designer and actors. The plays are given a budget of a mere $500 and no designers except for sound. Anne Erbe, the associate chair of the School of Drama Playwriting Department and the festival’s supervisor, considered these constraints similar to the challenges presented in popular TV shows such as “Project Runway” and “Top Chef.” She believes that deprivation fuels creativity.

“I think they are really frustrated,” she admitted. “But I think they come out on the other side happy in retrospect.”

As a project meant for playwrights-in-training, the deprivation serves a pedagogical purpose as well as a creative one. Nuñez recognized these constraints as pushing the playwrights to “write a play that lives on the page,” adding that the process forces him to focus on his language and how the actors’ bodies occupy the space, instead of focusing on extravagant design elements.

Nuñez also marked that having such a low budget allowed him to recognize the versatility of his play. “You could throw a lot of money at it — there is a nuclear explosion — but you could also do it for nothing, surprisingly,” he said.

Erbe mentioned how Nuñez wanted his play to be set in a confined space, yet the festival’s regulations didn’t allow him to build walls. This pushed Nuñez to think about sound and how to use the actors’ bodies to communicate a sense of physical restraint. These kinds of realizations are the reason behind the limitations for the Langston Hughes plays.

As an artist who is both a playwright and a musician, Nuñez compared the Langston Hughes process to playing an acoustic guitar. In his opinion, the pedagogy of the Langston Hughes is that “if a play doesn’t work without a million dollars, that play doesn’t work.”

“Eric Clapton could play the acoustic guitar, and the virtuosity would be clear. He doesn’t need a thousand petals,” Nuñez said.

For both Harris and Lubischer, the constraint of a tight budget was similar to the conditions they dealt with while producing plays for the Yale Cabaret. The shoestring budgets of both productions pushed them to their creative limits. Yet the Cabaret differs from the Langston Hughes in that the latter is essentially an academic project. Professors give feedback throughout the drafting process of the script, in addition to visiting rehearsal runs and providing comments. Harris said that the students who choose to come to Yale are students who like to get As and admitted it can become tricky to learn how to be gracious about receiving suggestions as well as following one’s own artistic compass.

This back-and-forth conversation is not only happening between the professors and the playwright, but also among all the members of the production team. Almost everyone working on the production is there to hone their craft and improve their skills. As Caitlin Griffin, the School of Drama’s associate director of marketing and communications, puts it: “They all have skin in the game.” This structure shapes the Langston Hughes plays into necessary collaborations which bring different challenges.

Tarell Alvin McCraney, the School of Drama Playwriting Department chair, explained how the main purpose of the Langston Hughes plays is to teach the playwrights how to work with their team. The material limitations are put in place to have the artists focus on collaboration with their colleagues. In his opinion, coming into the room with a single vision is not compatible with theater as an art form.

McCraney believes that the Langston Hughes process is meant to teach the playwright how to let the various ideas of the production team inform their vision, and “make it stand up.” McCraney also remarked that out in the professional theater world “the swiftness of theater making” can make writers forget the value of true collaboration as a team.

The playwrights have three weeks with their creative team to work through their initial visions for the play and adjust it to the needs of the production. Harris described this as a “luxury of time” he has been given to figure out his play. He said that his previous production experiences had been “very DIY.” He was used to starting with a script and a few actors, and having only a few days to put on a performance — there was no expectation to rewrite any part of the play before the production.

This has not been so for the Langston Hughes play.

Lubischer claimed that he starts his plays by writing questions to which he doesn’t know the answers and attempts to answer them with his actors, his director, the dramaturge and the rest of the production staff. He explained that he wants to go into the room thinking “I love this, I am curious about this, I am afraid of this, I don’t know what this is. Let’s figure this out.”

Nuñez also described the process as a way to test the reality of his play: “The actors are weather vanes for the truth, and in their bodies you see what is false, you see what is true, you see what works.” It is important for Nuñez to listen to both the opinions and the needs of the others working on the production: “Just because I have thirty new pages doesn’t mean that I can march into the room and stop what they are doing. … My every single impulse can’t take over the moment.”

The Langston Hughes plays are also the first projects the School of Drama playwriting students present to the public. This new component provides the playwrights with the opportunity to test their works with a real audience and keep developing the plays based on their observations.

“You can use the audience as a litmus test for when a play is really succeeding and when I want to tweak it for the next production or draft,” Lubischer noted. “We are not writing these plays for Yale, we are writing these plays for the American theater.”

Harris also wishes for his play to be impactful within a greater societal context. He described how plays tend to “exist for people to say I saw it but not for them to shift in any way,” and that it is important for his play to create “seismic” emotional and social changes.

Erbe and Griffin also acknowledged the urgent nature of the plays. They agreed that the line up this year is especially intense, and Erbe described it as “three artists writing and working on their craft while looking out at the world that is sort of burning down,” referring to the “feeling of a world in crisis, that is different in character to previous years.”

But, Griffin also mentioned that the Langston Hughes plays always tend to be more “bare bones and raw” than the Carlottas, or the third-year plays, which are fully produced over the course of several months. She believes that for the Langston Hughes plays, the playwrights rely on the audience to help them finish their thoughts.

While their first productions might seem fairly rushed, many Langston Hughes plays go on to be produced in the real world. McCraney’s own play as a second-year playwriting student in the School of Drama has been produced many times. Christina Anderson’s DRA ’11 “Good Goods,” which she first staged as a Langston Hughes play, has been produced by the Yale Repertory Theater. Now the interim head of playwriting at Brown University, Anderson reminisces about her Langston Hughes play as a pivotal moment in her life.

While the Langston Hughes plays have always been open to the public, this year marks a time when efforts have been made to make them even more accessible. The addition to showtimes on Thursday, 8 p.m., as well as the significant increase in the number of seats available to non-School of Drama audience members, make the Langston Hughes Festival more community-oriented than before. The festival starts on Oct. 26th, and there will be four performances each week for the next three weeks, one play per week in the following order: “Slave Play,” “In the Palm of the Giant,” and “Perfectly Timed Photos Taken Before a Disaster.”

Eren Kafadar | eren.kafadar@yale.edu .