It took New Haven 183 years to notice Yale’s property tax exemption.

And it was architecture, not paperwork, that caught the city’s eye. The University, originally bounded by the permeable Yale Fence, began to turn its back on New Haven and the Green. Once a small college serving Connecticut men of the cloth, the University had developed into an academic hub, and it needed a campus to match. Yale made a point of distinguishing itself from the chaos of an increasingly industrial city.

By 1899, what modern Yalies call Old Campus had come to cast a long shadow over the city. But New Haven would not let Yale reject its city without a fight. Yale made the first move through buildings, and New Haven would hit back through the property tax.

Though New Haven’s legislative action and the ensuing court case faded into the pages of history, the tax issue did not. And school and city never resolved the broader question that lurks in every Yalie’s mind: What role does Yale play in the Elm City?

—

Long before New Haven or Connecticut took issue with Yale’s nonprofit tax exemption, the state and city provided the startup capital necessary to grow the school into an asset. In these early years both the colony and city of New Haven were models of success. The port town enjoyed a healthy economy, a well-educated population with minor socioeconomic disparity and little social anguish thanks to its relatively homogenous New England Protestant makeup. In these years, New Haven was self-assured and optimistic.

In 1701, the colony of Connecticut voted from its legislative seat in New Haven to approve the charter of what was then called the “Collegiate School,” including some provisional funding for the purchase of land and the income of administrators.

The young school operated out of Killingworth — the roost of its founding rector, Abraham Pierson — until selecting the town of Saybrook as its official home. The founders envisioned the college as a place “wherein youth [might] be instructed in the arts & sciences [and] through the blessing of Almighty God may be fitted for public employment both in church & civil state.”

By 1716, many Connecticut towns had taken note of this college blooming in isolation and began to bid for the Collegiate School to relocate. New Haven, just over 30 miles from Saybrook and then one of the co-capitals of Connecticut, successfully outbid the opposition. The young college could not turn down New Haven’s generous offer of funds. After all, it had little money of its own and heavily depended on the public wealth. In response to this blatant monetary favoritism, Saybrugians took to the streets in outrage. When Yale reorganized its housing in the 1930s, it decided to pay tribute to its hometown by naming one of the original 10 residential colleges “Saybrook.”

As long as New Haven remained the doting host of a reputable, but not too powerful college, the town-gown relationship was happily stable. Even the Revolutionary War and the ratification of the United States Constitution didn’t rattle relations much. Connecticut and New Haven poured more money into Yale, and elected state officials served as fellows of the Yale Corporation.

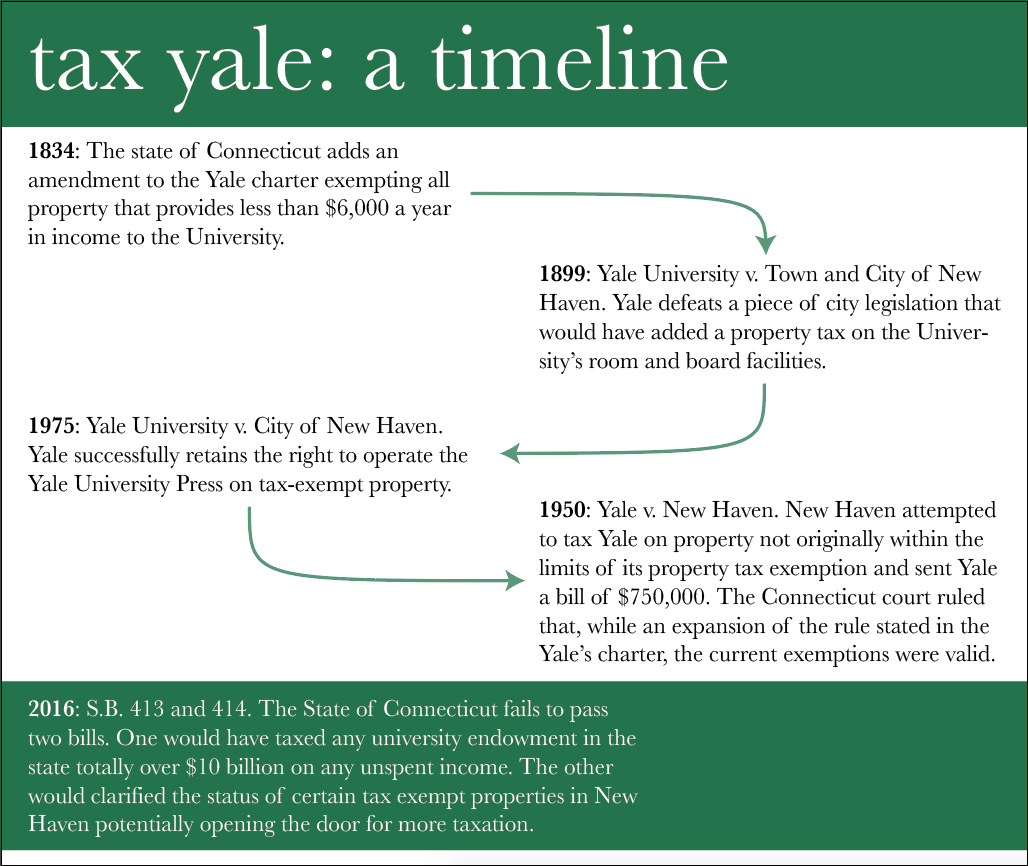

In 1834, an amendment to the University charter clarified that all Yale property would be tax exempt excluding those properties that generated income of more than $6,000 a year. This particular addition became the subject of great debate among critics and supporters of Yale’s fiscal status.

New Haven’s economic dominance through the 19th century meant that Yale was given space to develop with support from the city and state. By the late 19th century, when changes across the national economic landscape spilled over into idyllic Connecticut, the relationship started to change. New Haven and its deep-water harbor welcomed the industrial revolution with open arms, heralding a new age of commerce and growth.

New Haven’s population jumped from around 40,000 to a little over 100,000 in less than 50 years. The old way of doing things seemed to be slipping away as immigrant populations brought new jobs, culture and flavor to the growing industrial hub. It was in the midst of this communal upheaval that Yale turned its campus inward in a reactionary display of independence.

The 1899 court case, which protected Yale’s academic property from taxation, leveled a blow against New Haven signaling a change in the winds of college-city partnership. Gone were the days of Yale leaning on the helping hand of New Haven.

Nevertheless, New Haven entered the American Century with its head held high, brazenly assured that successful commerce and industry could more than make up for Yale’s cold shoulder.

By the 1930s, New Haven could no longer ignore that Yale, with its massive property tax exemption, was doing far better than the city as a whole. The broad shoulders of city sagged under the heavy weight of industrial decline.

Journalist Arnold Guyot Dana wrote a book in 1937, which studied the future of New Haven and determined that the Great Depression alone could not account for the negative trend in the city’s economy. Dana explicitly pointed out the growing number of tax-exempt properties, the flight of wealthy residents to the outskirts of the city and the poverty of the inner-city immigrant population.

The decline of New Haven shifted the balance of power to the University and its internationally acclaimed reputation. As Yale increased the size of its student body and faculty, it put new pressure on municipal services, noted Harvard Kennedy School of Government professor Peter Dobkin Hall.

Yale’s increasing external focus drove yet another wedge between the school and city. New Haven no longer benefited from Yale’s educational services as directly. While College enrollment tracked Connecticut enrollment closely through the early years, the first 30 years of the new century saw Yale’s enrollment doubled to nearly 6,000. Connecticut enrollment hovered below 2,000. The state of affairs did not look good.

World War II put issues of Yale’s sustained growth and the contemporary urban decline on hold. However, as the city moved into peacetime, it had to reckon with the fact that now more than 40 percent of its “grand list” — potentially taxable property — was exempt.

The Connecticut court once again backed the University and its exemption in 1950. In both 1950 and 1975, the courts extended the scope of Yale’s property tax exemption liberally. Both of these losses hit New Haven at a time of increasing economic uncertainty.

Connecticut stepped in with a “Payment in Lieu of Taxes” program in the 1970s to alleviate some the pressure on New Haven and other cities struggling with the dominance of tax-exempt nonprofits. However, the PILOT program has been historically underfunded in Connecticut.

In 1990, following insufficient relief from the state government, New Haven made a deal with Yale. The deal, orchestrated by then–University President Benno Schmidt and then-Mayor John Daniels, ensured that Yale would make an annual voluntary contribution to help New Haven out of short-term fiscal troubles in return for the assurance that New Haven would end the pursuit of a change in Yale’s property tax status. Yale now makes a $7.5 million annual voluntary contribution to the city of New Haven, the largest of any such contribution by a university to its host city.

Still, New Haven’s revenue problems are far from solved. While Yale owned more than $3 billion worth of property in the heart New Haven in 2016, the University paid only around $116 million in taxes on that land to the city. Yale was the fourth largest taxpayer on the city’s books despite being the city’s second largest employer and largest property owner. The United Illuminating Company was the largest source of property tax revenue to the city of New Haven in 2016.

—

New Haven’s identity struggles lay bare the issue at the heart of the Yale–New Haven tug-of-war: New Haven is not a conventional college city or town. Unlike New York or Pennsylvania, the city’s central business district hosts the University. However, unlike Hanover or Princeton, the city has an identity and an economy that operate apart from the University’s presence.

For both big cities hosts and small college towns, the power dynamic is clear. The school and the cities or towns can move past the internal politics and operate in the interests of whichever entity dominates.

Dartmouth professor William Fischel, an expert in the economics of land use regulation, singled out Dartmouth as an example of a nonprofit with a more narrowly defined range of tax-exempt property: the town can tax dormitories.

“The bad part is that it makes it expensive for Dartmouth to build residence halls,” Fischel said, laying out the pros and cons. “The good part is that Dartmouth and Hanover get along swimmingly. Hanover is not at all reluctant to have Dartmouth build residence halls.”

Unlike Dartmouth, Yale’s attempts to expand housing have often come with much political maneuvering — and not always to a successful end.

“So, in one sense, the taxability of some college property is a good thing for the college because it makes it a little bit more welcome. And on the other hand it does deter, financially, the college from [building].”

The limitations on Dartmouth’s tax exemption date back to the period following Dartmouth v. Woodward, a United States Supreme Court case in which the high court ruled that a charter constituted a contract and, therefore, could not be abrogated by a state. In a period of bitterness between state and school, New Hampshire passed a law allowing municipalities to determine the appropriate level of taxation for nonprofit private colleges and schools.

This oddity in state law allowed Hanover to set a tax on Dartmouth’s non-core academic property. Fischel pointed out that, though the tax policy has encouraged a mutually beneficial relationship for the most part, Dartmouth has found ways to “vote with its feet” and avoid excessive taxation.

“Dartmouth College used to be home also of the local hospital, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center,” Fischel said. “About 20 or 30 years ago, they tried to expand in Hanover and ran into a number of issues, one of which was land use regulation. So, they gave up on Hanover and now the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center is in Lebanon, New Hampshire, one town over.”

On the flipside of the Dartmouth-Hanover symbiosis is the Payment in Lieu of Taxes program, also known as PILOT, of Boston and its nonprofit sector, which includes several private universities and other nonprofits. Unlike New York City, which can fall back on local income taxes and sales taxes, Boston leans heavily on property taxes as a source of revenue.

Boston, the recipient of the largest amount of PILOT money in America, developed a formula to assess the percentage of government services that benefits nonprofits. Through a proprietary algorithm, the city found that nonprofits who do not pay property tax in Boston benefit from around 25 percent of public services. This calculation allowed Boston to establish a PILOT program that treated all nonprofits equally.

In the end the city requested 25 percent of the estimated lost property tax revenue in voluntary payments. Boston’s largest property tax exempt organizations, including universities and hospitals, agreed to this system. Daphne Kenyon, an expert in Payment in Lieu of Taxes programs, and her colleagues now hold up Boston as a model PILOT program.

One key distinction between Boston and New Haven, however, lies in the makeup of the nonprofit sector. Where Boston’s third sector comprises 46 organizations that are included in the PILOT program, New Haven has only two — the University and Yale New Haven Hospital. This reality makes it more difficult for New Haven to set a rule because any such attempt would appear to target Yale and the hospital specifically.

“A lot of the judgment of fairness is worked out in the court of public opinion,” Kenyon said. “People might be swayed by information like how much the president makes, how many Yale students are from New Haven or how big a fiscal crisis is New Haven going in for.”

New Haven benefits from a slightly different PILOT system than does Boston and other municipalities across the country. While many major cities receive payments directly from the tax-exempt nonprofits, New Haven receives its compensation from the state of Connecticut. Rather than negotiating directly with nonprofits, Connecticut promises to reimburse 77 percent of lost property tax revenue in the form of PILOTs.

“What almost always happens is, if a state is in severe fiscal distress, it passes some of that onto local governments, I hate to say,” Kenyon said. “I don’t know that [the state has] ever fully funded its promise, and, if it hasn’t cut [PILOTs], I think there is a good chance it may.”

According to the most recent property value assessment in the fall of 2016, New Haven’s tax exempt properties have appreciated 22 percent, a total of just under $1 billion. This appreciation should correlate to a rise in PILOT revenue from the state, but Connecticut’s fiscal problems have pushed the program far down the list of budgetary priorities.

In fiscal year 2016, Connecticut reimbursed New Haven with $7,465,427 compared to a $15,208,516 owed according the PILOT statute. The state’s reimbursement program currently returns only 23 percent of New Haven’s total revenue losses due property tax exemptions.

—

It’s not yet clear what type of city New Haven is and where it will end up. It is no longer the genteel New England town that it was at the founding of the University, but nor is it the low-wage, industrial city of the turn of the century.

This identity crisis looms large in the minds of New Haven residents and its politicians. Marcus Paca, a challenger in the Democratic primary for the mayoralty, sees the questions of New Haven’s identity deeply entwined with the role the University will play in New Haven’s future.

“A lot of people demonize Yale when in fact they’re a private institution that contributes a lot of valuable resources and insight into our communities and city as a whole,” Paca said. “But what I do believe is that we need to be more communicative about the needs of New Haveners and how Yale can help better our communities.”

Paca did not, however, express hope or vision for a change in state law that would substantially increase Yale’s tax burden.

In the spring of 2016, debate opened on the floor of the Connecticut General Assembly on a bill that would clarify the nature of Yale’s property tax exemption. Though the bill would not have tightened the reins on the exemption as much as in New Hampshire, it might have allowed New Haven to add a few more of the more ambiguous properties to its grand list.

A Yale-produced document noted that the senate bill would require Yale to pay annual taxes of nearly $760,000 on Woolsey Hall alone, just one of the many properties that would be subject to the property tax had S.B. 414 passed.

The bill was one of two introduced on the floor that spring. State Sen. Martin Looney, a Democrat who represents New Haven, introduced a partner bill that would have required Yale to either spend more of its endowment earnings or face that income getting taxed. This proposal would have, in theory, forced Yale to lighten students’ tuition load, improve facilities or otherwise serve the student body, or else face a tax.

These proposals represent a shift from previous efforts to increase tax revenue from Yale. The shift manifests in two ways. First, most efforts to tax Yale’s property originated in the city of New Haven itself and, often, tied into the underlying discomfort at the city level over the changing town-gown dynamic. However, the 2016 bills originated at the state level under budgetary pressure. Second, this marks the first time Yale’s endowment has been the subject of a proposed tax on the state or local level.

At the end of the day, neither bill made it far. Looney’s endowment tax proposal did not even make it out of committee. But the question, once raised, cannot be avoided: What role will Yale play in the future of the state?

Yale and New Haven resolved their legal disputes in 1990 with the school’s promise to make annual voluntary payments. Their relationship currently rides on whether Yale sees New Haven as a fixture of its past or as a permanent part of its present identity.