“Keep the Body, Take the Mind”

Connecticut Law Enforcement, Forced To Rely Heavily on Traumatized Victims, Hamstrung in Child Sex Trafficking Cases

The Berlin Turnpike is a 12-mile strip of road that passes through four small Connecticut cities. Nearly 40 motels, some with pay-by-the-hour rates, flank the highway, catering to the scores of truckers that pass through the state every day. Many travel through central Connecticut. Few understand that the Berlin Turnpike is also one of America’s most notorious arteries of child sex trafficking.

In March, I spoke with workers and managers at 15 highway motels — 10 along the Berlin Turnpike and five in New Haven. Most had heard that sex trafficking exists, but believed it to be a problem in other motels, not in theirs.

In Connecticut, the number of domestic minor sex trafficking cases has grown dramatically over the past decade, in step with nationwide trends, according to statistics from Polaris Project — a nongovernmental organization that works to prevent forms of modern-day slavery — as well as federal and state officials. The spike is putting pressure on the state to pass legislation and deliver justice for the most traumatized victims: child sex slaves.

A 2016 law, effective since Oct. 1, seeks to strengthen the state’s anti-trafficking statutes and mandates that all hotels, motels and inns in Connecticut post a sign with the phone number for the National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline. The law also requires all current lodging employees to be trained to notice the warning signs of sex trafficking by Oct. 1, 2017, and managers to maintain records of customer transactions for at least six months.

No one I spoke to had heard of the law.

According to Amar*, manager at the Coronet Motel, the “reputation is that Berlin Turnpike is full of seedy people, but it’s not that bad.”

Since 2006, when Connecticut became one of the first states to pass a trafficking in persons felony charge, the state has ramped up its anti-trafficking efforts through more legislation, increased awareness and expanded resources for victims. Still, the state struggles to investigate these cases and convict traffickers. The reason is that the state’s legal system currently limits law enforcement’s ability to collect evidence, forcing investigators and prosecutors to rely on child victims to cooperate and provide accurate evidence and testimony.

But due to the horrific psychological and emotional trauma that victims endure in the sex trafficking underworld, the children often do not cooperate or are unable to provide accurate evidence or testimony, making it significantly more difficult for law enforcement to investigate and prosecute traffickers.

These facts are based on interviews with one victim and nine dedicated Connecticut officials, as well as the tape from a 2016 Trafficking in Persons Council roundtable — a state-commissioned committee that collects data, issues reports and makes recommendations to improve Connecticut’s anti-trafficking efforts — as well as government documents.

The Connecticut House of Representatives is currently debating a grand jury reform bill that would expand the power of law enforcement in evidence acquisition.

When little evidence exists or is difficult to obtain, victims of child sex trafficking become even more important sources of information, according to Brian Austin, executive assistant state’s attorney. However, the psychological damage of being a child sex slave cuts deep and may be permanent. It can plunge the victim into a world of denial, abject acceptance, exaggeration or delusion.

According to Jutta Joormann, Yale professor of psychology, there are coping mechanisms that can help victims adapt to their harsh realities. “People are very good at surviving, even in desperate situations,” she said.

I saw this firsthand when I met Kaitlin* at a women’s recovery center in New Britain in April. Our first interview, which was nearly two hours, was tape recorded with her permission. Janet*, the center’s founder and executive director, witnessed the interview. Kaitlin and I communicated through text, on the phone and once more in person. For the sake of privacy, I have changed their names.

Below, I’ve written Kaitlin’s life story as she told it to me. Parts of her story appear true, though I discovered that crucial moments in her history did not happen the way she described. I was unable to corroborate most of her story.

Even though she is not a completely credible source because of inconsistencies in her story, I have decided to share it anyway. With little outside evidence, one can only rely on Kaitlin to explain her story as she believes it to have happened. Indeed, law enforcement often faces the same dilemma in child sex trafficking cases.

Krishna Patel, a former deputy chief of national security and major crimes at the United States Attorney’s Office who prosecuted many child exploitation and human trafficking cases from 2003 to 2015, said she had to parse through victims’ stories to gauge their credibility. Patel is now the Justice Initiative director and general counsel at Grace Farms Foundation in New Canaan.

According to Patel, the victims may have to testify about extremely painful memories. A good defense attorney will try to exploit the holes in a story that may be an extension of the trauma.

“It feels very cruel about our criminal process,” she said.

—

Kaitlin said opening up about her past would make her vulnerable, but that would help her in the recovery process.

“I feel like I may be able to help somebody after I do this,” she told me.

Kaitlin’s childhood home from 1999 to 2003 was a room at the Super 8 motel in Hartford where she lived with her mother Diane*. She described it in vivid detail. It had yellow walls and a small round table in the right corner where her mother spread her drug kit: bags of syringes, crack pipes, crack, heroin and lighters. One of the bags even had Kaitlin’s initials on it. Beer cans and bloody towels were strewn across the floor. The smell was horrific. The air was smoky from the cigarettes and musty from Diane’s poor hygiene and sweaty men.

When Kaitlin was young, she would fold her clothes and stack them neatly in the corner. Every night before bed, she counted all of her outfits — one, two, three — and placed her shoes next to the door. She felt more secure with all of her possessions in one place. Sometimes, though, she would wake up and everything was gone, sold by her mother for more heroin.

Diane sold Kaitlin’s body for heroin, too. For four years, from ages 13 to 17, Kaitlin and her mother spent their days walking down Green Street in Hartford. The street, she said, was full of prostitutes, drug dealers and alcoholics.

Diane would solicit men sitting idly in their cars. Kaitlin isn’t sure what her mother would tell the men, but after a few minutes, they would be on their way to the hotel. Diane advised Kaitlin not to wait for the men to ask her to take her clothes off, so she would immediately strip down naked upon entering the room. Diane would put pornography on the television and sit at the table where her drug kit was set up. As she got high, the men would rape Kaitlin — sometimes for as little as $5. Diane always watched.

“It was a full-time job for me,” Kaitlin said.

The rapes were painful, but “mommy’s medicine” — heroin — helped Kaitlin. She was 13 years old the first time her mom injected her. Diane told her that she would no longer have to feel the things the men were doing to her.

Diane tied her daughter’s arm so that the vein would bulge. She stuck the needle in near the elbow and drew the plunger slightly so a few drops of blood filled the barrel of the syringe. And then, with a gentle push, Diane spread heroin throughout Kaitlin’s body.

The high was “amazing,” Kaitlin said. “Everything I was feeling a minute ago, being raped 10 minutes before that … everything went away.”

—

In 2008, the Connecticut Department of Children and Families began receiving reports that girls from the child welfare system were being sexually assaulted and raped.

After some investigation, DCF learned that these children were running away and being pulled into the life of human trafficking. Tammy Sneed, director of Gender Responsive Adolescent Services at DCF and leader of their Human Anti-trafficking Response Team, said DCF receives calls through the “Careline” from anyone in the general public concerned that a child may be a victim of abuse or neglect, which includes calls related to child sex trafficking.

Since then, DCF has received more than 630 referrals for children who are suspected or confirmed victims of trafficking. That number has risen annually for the last five years, in part because of greater awareness, as well as better reporting and tracking methods. In 2016, DCF received more than 200 referrals — the most in a single year, according to the department’s statistics.

As the number of referrals continues to climb, there is a greater impetus on state law enforcement to tackle these cases. Federal authorities, for lack of manpower and resources, cannot handle all of them. According to Alicia Kinsman, a lawyer at the International Institute of Connecticut who has represented victims of trafficking, DCF has reported a lot of referrals to state and local law enforcement and “almost none of those cases went to a full investigation or criminal prosecution.”

State prosecutors earned only two convictions under the class B felony charge of trafficking in persons between 2006 and late 2016, according to the most recent Trafficking in Persons Council Annual Report.

“If referrals are high, we want to make sure that each victim has a chance at justice. We need to be using every avenue we can,” Kinsman said.

For a crime like sex trafficking, which often happens in shady highway motel rooms under the cover of night, evidence may be hard to collect. Traffickers tend to leave few traces behind.

Potential sources of evidence like cell phone records, motel files, GPS information and Internet data are crucial for the investigations, sources said. However, Connecticut law enforcement cannot use them because the state, without a traditional grand jury system, lacks subpoena power in most cases.

Grand juries are secret groups run by prosecutors that have the power to summon testimony and evidence before deciding to move forward on criminal charge. Some state-level grand juries have more power than others. Connecticut has a highly restricted system — an investigative grand jury option, consisting of three appointed judges, which has seldom been used in more than 30 years. Under the Connecticut system, state prosecutors must try all other methods of investigation before submitting a request for a grand jury, which can still be denied. It could not be determined if the grand jury option had ever been used in a child sex trafficking case.

While the number of referrals has been higher than expected, Sneed believes “our numbers are underrepresenting what’s actually happening.” The fact that many victims do not see themselves as victims makes it hard to verify cases.

According to Joormann, children need to feel attached to an adult authority figure, even if that person is doing them harm. They may think their situation is normal.

“As a victim, you need to survive,” Joormann said. “[Traffickers] know how to exploit that.”

For traffickers, exploitation is an art, learned through trial and error and taught in literature. Traffickers’ preferred methods for ensnaring and controlling women and children are easily found in books sold by mainstream vendors like Amazon.

Pimp literature, as it is known, offers a bizarre look into the pseudo-intellectual foundation upon which this form of modern-day slavery is built. There are pimp memoirs, like “Pimp” by Iceberg Slim, and novels like “Whoreson” by Donald Goines. Other books like “The Pimp Game: Instructional Guide,” “How to Get a Woman to Pay You” and “The 48 Rules of the Game” focus on the science of mental manipulation, which is fundamental to pimping.

One convicted trafficker— Corey Davis, who was sentenced by a federal judge to 24 years — kept in his possession a book titled “The Willie Lynch Letter and the Making of a Slave,” according to an evidence list from the case. The book’s authenticity is widely questioned, but lore says it was delivered as a speech by a slave owner named Willie Lynch in Jamestown, Virginia in the early 18th century. The topic is how to break and control slaves. At one point, the speaker instructs slave owners to “KEEP THE BODY, TAKE THE MIND!”

These books are pervasive in the underworld. Patel said “pimp culture” plays out as a violent crime, and traffickers’ primary psychological weapons are “fear and trauma.”

The damage can be so severe that it results in a bond — even love — between children and trafficker, and children tend to be extremely loyal. The trafficker “is the only person [the children] believed loved them and they loved,” Patel said.

For the children, being taken from their trafficker can be extremely traumatic. According to Patel, the children “never see you as wearing the white hat.”

“They are spitting at you and yelling at you,” Patel said.

—

When Kaitlin was taken from her mother at age 17, she didn’t scream or spit. The last time she was raped as a child was so brutal, so horrific, that she was silent — nearly catatonic — for a month.

The day started like any typical Saturday morning for Kaitlin: a walk down Green Street, drinking an iced tea while Diane looked for customers. She found two men in a car, and the group of four went back to the motel.

Like she always did, Kaitlin immediately stripped down naked. The men laid her down on the bed. But for the first time, Diane left the room. It was the last time Kaitlin ever saw her.

Kaitlin said the men penetrated her with objects: a dildo and a wooden stick with a rounded end. When Kaitlin started to move away, the man with the wooden stick threw her back on the bed. He beat her, bruising her face, legs and hind.

The rape continued for another hour. By the end, Kaitlin was soaked in blood, and her “woman area,” as she said, was badly bruised and cut from the wooden stick.

When the men left the room, she screamed as loud as she could. Someone from the front desk ran into the room and called the police, and Kaitlin called her grandfather. When he arrived, she recalled, “It was like he’d walked into a murder scene.” There was blood everywhere. She could barely open her eyes because her face had been so badly damaged.

Kaitlin was taken to a hospital. The damage to her reproductive organ was so bad, doctors had to sew her. Police, social workers, her grandfather and therapists questioned her. But Kaitlin couldn’t respond. She said her silence was not a conscious decision. She felt like she was responding, “but I couldn’t open my mouth. I just couldn’t trust them.”

Kaitlin remembered thinking, “Now you guys want to believe me?”

—

In 2006, Connecticut became one of the first states to implement a state-level felony charge for trafficking in persons. Patel was on the team that helped write the law.

Some years later, she said, an amendment was added in Connecticut that required “more than one occurrence of sexual contact” to elicit a violation. Patel was unsure why this amendment was added, and she called it “absurd” and “ridiculous.”

State prosecutor Austin said law enforcement would not allow a child to be raped more than once. In drug investigations, for example, an undercover officer may buy narcotics on several occasions to build a case, but trafficking cannot be handled in the same way because a child’s life is at stake.

Under that amendment, law enforcement officers faced a difficult reality. If there were reason to believe a child was being sexually exploited, law enforcement would always extract the child. But, Patel said, that meant “you [could] blow up the rest of your entire case” against the trafficker because the minimum of two sexual encounters had not been met, and the trafficker could not be charged with trafficking in persons under state law.

In 2016, the language was changed again when Connecticut passed an act concerning human trafficking. Now, state law is in accordance with federal law under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which says one sexual encounter is enough to charge someone.

The bill also created new regulations on businesses in which trafficking-related activity might take place. Now, hotel managers are required to maintain customer transaction records for at least six months, train employees to spot signs of human trafficking and — along with adult-only businesses and establishments with alcohol liquor permits — post signage “in plain view” with the phone number for the National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline.

In January, Connecticut Gov. Dan Malloy announced the beginning of a partnership with hotels to provide training to help lodging employees look for the warning signs of human trafficking. He called it a crime “that shocks the conscience.”

He added that he supports the legislation, which “strengthens protections for victims” and “gives law enforcement the tools needed to bring perpetrators to justice and helps raise public awareness.”

—

Upon interviewing employees at 15 highway motels in March, it appears that the law has not yet made much of an impact. Of the employees I spoke to, none had heard of the law, even though parts of the bill had gone into effect more than six months prior.

No National Human Trafficking Resource Center signs were visible in any of the 15 hotels.

Jillian Gilchrest, chair of the Trafficking in Persons Council, was unsurprised though disappointed by the findings.

“You can pass the policy, but then there’s the issue of enforcement. We knew that there are no teeth behind it,” she said.

Every hotel I visited had an acrylic glass shield that protects the reception desk from the rest of the lobby. Receptionists and managers never emerged from behind the window; they preferred to speak through the hand-sized hole through which customers slip money. On the glass, some had hung up stickers from the Berlin Police Department that thanked them for their support.

The turnpike, most employees knew, has a bad reputation. Amar, the manager at the Coronet Motel, has heard that young girls are trafficked up and down the road and raped for money in hotels like these. But he screens his guests the best way he can; he doesn’t let in more than two people per room and tries to keep suspicious-acting people out.

The manager of a New Haven highway motel, who asked to remain anonymous, watches her hotel from camera footage, which she can view at home. She said the United States Department of Justice had subpoenaed her records two days before being interviewed.

She tries to be vigilant, but it is often difficult to identify “the bad people.” She told me about a time when she realized that a bank robber was hiding from law enforcement in her motel. She was watching the morning news when a picture of the man was posted on the screen. She immediately called the police, and he was arrested.

“We thought he was such a nice customer … But, people have double lives,” she said.

—

After Kaitlin was released from the hospital, she was put in her grandparents’ custody. She was 17 years old. There was about a six-month period in which Kaitlin was not having sex for money or doing drugs. She played basketball every day at the park near her house where she and her friends would shoot into “egg crates.”

“Besides heroin,” she said, basketball “was the next love of my life.”

Her grandparents put her through detox and a rehabilitation program.

When she turned 18 years old, she moved out on her own and back into the world of hard drugs and prostitution.

She missed her earlier life. “I was addicted to giving myself up, addicted to being raped, addicted to the drugs as well as the sex,” she told me. “I loved it.”

She said she was able to get into a four-year university and walked onto the school’s basketball team. She prostituted to fund her heroin addiction while playing at a top-tier program.

Heroin was Kaitlin’s “morning coffee.” She would inject herself on the lower part of her leg, which was covered by the high socks that her team wore. But when her coach drug tested the players, Kaitlin’s urine came out “dirty.”

The coach was incredulous, and confronted Kaitlin about the situation in his office.

“I just like started crying,” she said. “I just broke down and everything started coming out.”

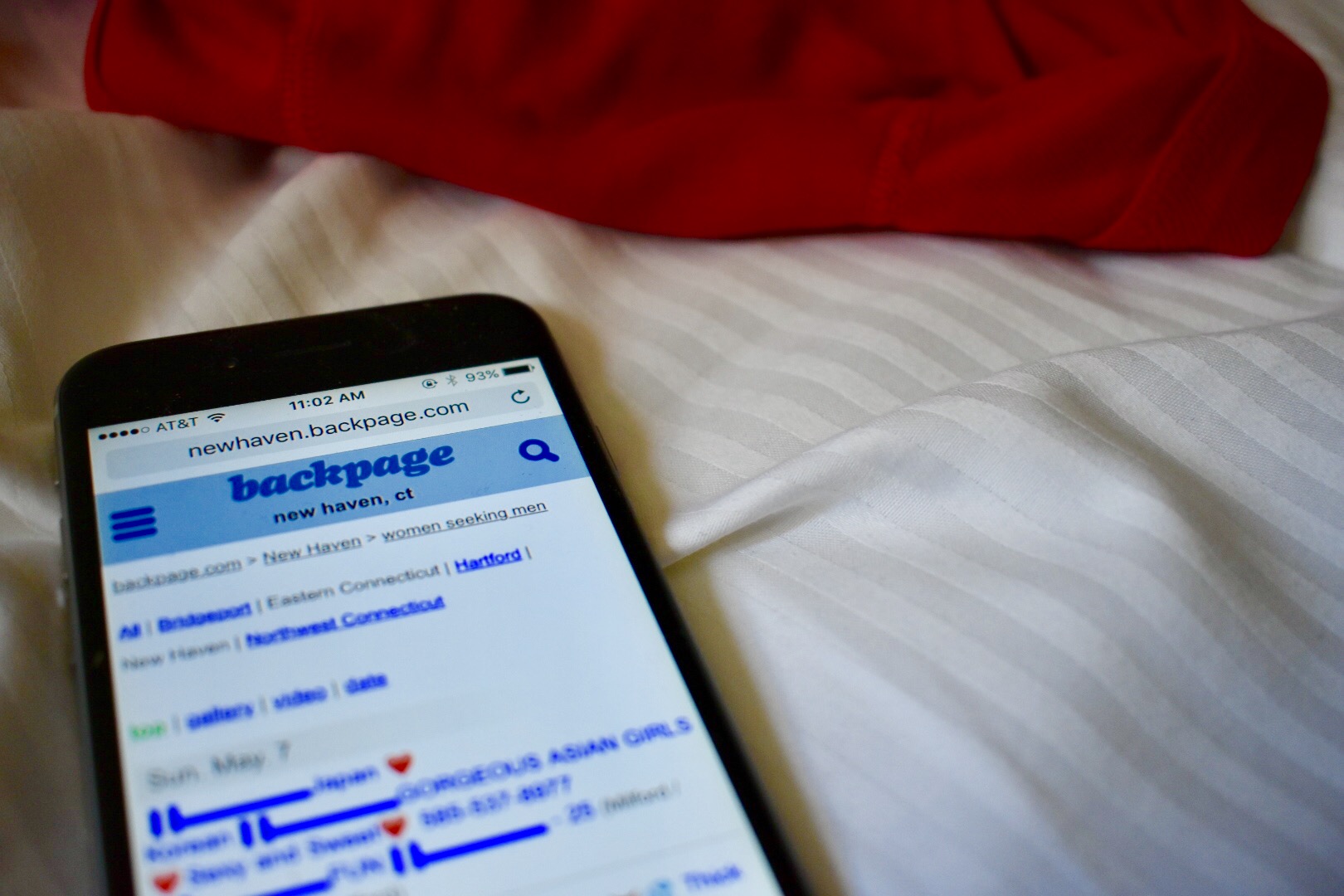

It was the first time that Kaitlin revealed that she was an addict, had a pimp and was selling her body online via Backpage, a website notorious for advertising sex with prostitutes and children.

Kaitlin’s coach said she had to move out of the hotel where she was prostituting. She had to get away from the pimp as soon as possible. “But that didn’t work so well,” she said. The pimp was vigilant, and often violent, in controlling her.

One day, Kaitlin recalled, she went to the hotel to pack up her things, but the pimp followed her.

As we spoke, she lifted up her shirt and exposed a two-inch scar on her stomach: “He stabbed me twice,” she said, pointing to the scar. “See here?”

Kaitlin dropped out of school soon after the conversation and descended back into “the game,” though she remembers the impact her coach had on her.

“Someone loved me,” she said.

“It’s very rare that someone comes in my life that believes in me and loves me for me and doesn’t look at me like the junkie, the prostitute the — you know — all those bad things I think I am.”

“So the support I got — I never took advantage of the support — and I think that is where I ran into problems because I would always brush it off. I was never open to letting somebody love me, and I think if I was and let him in more … I think I would have went down a different road.”

—

While reporting this story, I spoke with the director of women’s basketball administration at Kaitlin’s university, who spoke with the head coach.

“In simple terms,” the director responded in an email, “the situation you described did not occur.”

Kaitlin’s real name was not in the school’s internal database, according to an official in the registrar’s office. Neither was her name listed on the basketball team’s roster. Kaitlin does not appear in the team picture.

Other parts of Kaitlin’s story could not be confirmed or denied.

I asked her about the apparent discrepancy between this part of her story and my findings. Janet, the executive director of the women’s center, asked me to approach this topic very lightly for fear of bursting a psychological bubble that Kaitlin may have constructed due to the trauma. Janet asked not to be involved because she did not want to undermine the trust that she and Kaitlin have built over the past few years.

Kaitlin doubled down on her claim that she played basketball at the university and then added in a text that the head coach had been her “trick” — a customer — for two years.

She responded, “Why would I tell you something that you could easily look up?” She also sent me her former address from an off-campus apartment near the university.

The women’s center monitored Kaitlin carefully after I spoke with her. Based on my last conversation with Janet, Kaitlin has not shown any signs of relapse.

Sex trafficking victims often undergo prolonged trauma that can last for years. Joormann explained that victims of long-term trauma can suffer from many psychological issues, ranging from post-traumatic stress disorder to delusions. A victim may pick out something that they’ve heard on the news, or something that is on their minds, and make it their own.

On Kaitlin’s apparent belief in her story, Joormann said, “In her mind, it may be real.”

—

In March 2016, the Trafficking in Persons Council hosted a two-hour roundtable. Some of the state’s top policy makers, senators, federal and state prosecutors were present to discuss why no convictions had occurred since the felony charge was enacted in 2006. (After the meeting, there were two convictions in 2016.)

The problem, Chief State’s Attorney Kevin Kane said at the meeting, is that Connecticut has to begin making “cases that don’t entirely depend on the victim’s testimony.”

Connecticut does not have a traditional grand jury system. Therefore, the state has a much harder time obtaining evidence like financial records or phone call records than federal prosecutors or prosecutors in other jurisdictions who can get access easily through the grand jury subpoena power.

Sometimes, Kane added, Connecticut state law enforcement does not even have enough probable cause for a search warrant, further impeding the state’s case against the trafficker.

On the other hand, the federal system uses a grand jury and has subpoena power. According to former federal prosecutor Patel, this allows prosecutors to corroborate evidence that can fill the gaps in a victim’s testimony like motel records, GPS locations and cell phone and Internet data.

Since 1983, Connecticut has charged crimes through “complaint or information” rather than a grand jury indictment. While a trafficking in persons charge falls under the purview of the investigatory jury, sources said this option has never been used. A search could not confirm this.

If law enforcement is able to build enough evidence for a case, victims still may prove unreliable. Gilchrest said the outcome of the cases often depends on the victim.

“Often the youth are so traumatized that they are not seen as a good witness,” she said.

The system, according to Kane, “makes the victim extremely vulnerable, especially when the defendant realizes the case rises and falls on the testimony of this one victim.”

He added, “if [traffickers] can take the victim out of the case — one way or the other — there’s no case against them.”

For the first time in more than a decade, according to Austin, a grand jury-reform bill has passed the Connecticut House Judiciary Committee. Austin said subpoena power would open up a new set of tools that prosecutors could use in child trafficking cases.

The evidence that law enforcement could access may alleviate the pressure that victims feel to make their own cases. This is especially useful when many of the children do not see prosecutors and police officers as trustworthy and do not cooperate.

However, in a written testimony opposing the bill, David McGuire, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut, wrote that the bill grants overly broad powers to law enforcement and would “practically invite constitutional violations of the Fourth Amendment …”

According to a spokesperson for State Rep. William Tong, D-147th District, who sponsored the bill, it can go to a vote in the House of Representatives any time.

—

Kaitlin is 32 years old now, and she’s doing much better than ever before. She has not been raped for many years and is more than 17-months clean, her longest period of sobriety since she became a “full-blown junkie” at the age of 15. Every day she wrestles with the pain that she endured in Connecticut’s sex trafficking underworld and is scared of what the future might bring.

“I am dealing with my trauma. There are days I want to give up,” she said. “I don’t want to go back to heroin and sleeping with these guys.”

People are listening to Kaitlin now, too. In April, she told a packed room of more than 600 people at a fundraiser for the women’s recovery center how her mother Diane had trafficked her out of a Hartford hotel room for heroin money when she was just 13 years old.

She told me that, as a teenager, she tried to reach out for help — to find someone who could stop the rapes. No one believed what was happening to her: not her grandfather, not her mother’s “sugar daddy,” not the Connecticut Department of Children and Families.

“I just think people didn’t expect a mother to do that to their child,” she said.

Kaitlin said she is not sure what happened to “Juicy,” her former pimp from college. He went to jail for some time, but she lost track of him and hopes never to see him again. As for Diane, Kaitlin said she was found dead on the side of a Connecticut road roughly three years ago.

Kaitlin is trying to put the pieces of her life back together. She wants to get married and start her own landscaping company someday. For now, she lives moment by moment, focusing on her recovery.

This time, Kaitlin said, things are different. Her old life is behind her, and she’s cautiously optimistic for the future.

What has changed? For the first time, she said, she’s letting people care about her. She’s not going to push people away as she has in the past.

She has also started putting her faith in God, whom she once hated. “This is a big thing for me,” she said.

Kaitlin believed in God, but she “hated Him, held resentment for Him.” She said she didn’t understand why God put her through the life she had.

But this past year, she finally let Him back into her life.

“I let it all go and put it in the hands of Him,” she said before pausing. “It has been nothing but good.”

*Names have been changed or modified for privacy reasons.

Correction, May 22: A previous version of this article misstated that Tammy Sneed’s Human Anti-trafficking Response Team set up the “Careline.” In fact, the “Careline” had already been in place.