“Ask not what you can do for your country. Ask what’s for lunch.”

—Orson Welles

The man rattled off his order to the woman behind the register without pausing for breath or second thought: “Chopped-up, fried, crispy chicken wings.” She ladled a few wings out of the bubbling vat behind her, then brought a thick blade down through the crunch of bones, tossing the mutilated chunks into a Styrofoam box alongside some french fries crimped like accordions. While the first man migrated to the ketchup and hot sauce bottles at the edge of the counter, another one shuffled up. “Can I have a mustard?” he asked.

A dozen more customers passed in and out. Some ate their orders at one of four lacquered-top tables, but most took their food to go. More chicken got chopped. After 45 minutes, the place cleared out, leaving just the woman at the counter, the hiss of a frying pan and the viscous odors of grease and sweat. The woman glanced into the corner where I had camped out to observe every interaction like an overeager teacher’s pet. She looked amused. “I told you, there’s nothing to write about here,” she said in Mandarin. “My story is just like the story of any other Chinese restaurant.”

—

Lin Zheng* owns China King, a nondescript takeout joint in downtown New Haven that looks a bit as if it just went out of business. The tall capital letters spelling its name above the door are a dull burgundy, like the unplugged neon lights of an abandoned casino. A banner in the window displaying the restaurant’s phone number, upon closer inspection, is three pieces of taped-together computer paper. A fold-out sign on the sidewalk advertises that “Chinese Food” is sold inside, but the marker is faded, lending the announcement an air of exhaustion. Less than a block away are the redbrick turrets and dignified arches of Yale University; I doubt many students know that China King exists.

China King attracts a different crowd. Between opening at 11 a.m. and closing 12 hours later, the restaurant’s fluorescently lit, pink-tiled interior is filled with people in Chipotle and Subway uniforms barking orders at Lin for chicken wings, chopped up — and fast, because their break is almost up. “I ain’t got time! That’s why I called ahead!” a man in a Metro-North jacket exclaimed one night in frustration.

By my admittedly unscientific calculations, China King produces at least half a dozen orders of chicken wings and fries an hour. Lin, a short woman with soft, childlike features and an apron the color of sweet-and-sour sauce, says the most popular order is General Tso’s chicken, and there’s an enormous rice cooker five times the size of my head in the kitchen. But it’s the fried chicken vat that sits closest to the register, and it’s the fried chicken vat whose depths I see most customers plunder. There are 207 items on the menu — a dizzying directory of lo mein, egg foo young and moo shu shrimp — but “fried chicken wings (4)” occupies a place of honor second from the top, right under “fried half chicken.”

It makes sense, I suppose, that the top spot doesn’t belong to the green pepper steak or the bean curd with garlic sauce, two offerings that sound most like something my mother might make at home. During two months of weekly visits to China King, I counted only 10 Chinese customers other than myself, and seven of them were part of the same lunch group. Almost everyone on the brightly lit, northern side of the counter is black or Latino. (“Camarones fritos y arroz con puerco,” one customer instructed a confused Lin over the phone.)

On the southern side of the counter — an L-shaped fake marble slab stacked with paper menus, the ketchup and hot sauce bottles, and a persistently empty tip jar — is another world, or maybe just another country. In the dim, corridorlike, stainless steel kitchen, Lin and her husband, Chun, who cooks, call orders in Fuzhou dialect, a variation of Mandarin that is spoken in Fujian province on the southeast coast of China. When the restaurant is empty, the two other cooks watch Chinese game shows on their phones, the host’s theatrically exuberant tones rising above the hum of the industrial-size freezer. At mealtime, surrounded by pots of wonton soup and boats of goopy sauce the color of Maraschino cherries, the staff crouch on overturned buckets to sneak quick bites of white rice and stir-fried vegetables, sharing a platter of steamed whole fish, glossy eyeballs still intact.

Then the bells over the door jingle, a customer walks in, and Lin is back at the counter. She stands on one side. Her customers stand on the other. If she represents Fujian and they represent New Haven, the distance between is wider than any ocean.

—

To carry the cliche to its natural end, China King should be the bridge. Chinese takeout, after all, is an American institution. There are 40,000 Chinese restaurants in the United States, nearly three times more than the number of McDonald’s restaurants. Throw a dart at a map of America and you’re more likely to hit a wok full of beef and broccoli than a griddle lined with Big Macs.

The earliest Chinese restaurants in America would have been unrecognizable to today’s drunk college students, harried soccer moms and Jews in search of Christmas Day kung pao chicken. Opened in California in the mid-1800s by Chinese laborers, the first “chow chows” — Cantonese slang for “anything edible” — were run specifically for hungry Chinese. Some were holes in the wall, filled with poor railroad workers. Others were appointed with expensive porcelain and elaborately painted decorative screens, catering to wealthy Chinese merchants visiting San Francisco. All served food as close to that of the restaurateurs’ hometowns as possible. Early menus included options like shark’s fin, bird’s nest soup and fish sinews.

But restaurant owners soon realized that they had to appeal to a non-Chinese audience too, and apparently 19th-century Americans weren’t lining up for exotic animal appendages. So the menus quickly evolved. Not only did the Chinese offerings become sweeter and meatier — traditional Chinese cooking prizes vegetables — but they were also joined by classic American options, too, like mutton chops or steak Hollandaise. This new watered-down, Westernized menu, an ode to cornstarch and deep-fryers, spread rapidly around the country. Americans may not have loved Chinese people (see the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act) but they sure loved chop suey. Today, Chinese takeout menus across America feature virtually identical set lists of greatest hits, from suburban Chicago to rural Louisiana to downtown New Haven.

—

In red capital letters on the cover of China King’s takeout menu, beneath the restaurant’s name and above a sketch of an imperial palace, is a taxonomic declaration: “SZECHUAN, HUNAN AND MANDARIN CUISINE.” Szechuan and Hunan are landlocked provinces in central China famed for their red-hot, stomach-punishing cuisine; when I visited relatives in Hunan several years ago, I had to sneak out to McDonald’s after dinner because I couldn’t eat what my grandmother had prepared. Mandarin cuisine is another name for food from Beijing, which uses dark, sweet and salty sauces over wheat staples like noodles and dumplings.

Lin is from Fujian, a seaside province directly across the sea from Taiwan. Fujianese cooking, along with Hunanese and Sichuanese, is regarded as one of the eight great cuisines of China, but it couldn’t be more different in terms of taste. For every tongue-numbing Sichuanese peppercorn, there is a lightly battered Fujianese oyster cake; for every hearty dumpling in Beijing, a delicately braised seafood stew.

There’s nothing Fujianese on China King’s menu (not that there’s anything exactly Sichuanese or Hunanese either). At slow moments in the kitchen, Lin and her staff stir-fry snails and sip duck soup, but that food never crosses the counter. When I asked Lin if she had ever thought about introducing some of her native dishes to the menu, she looked at me like I had asked for spaghetti and meatballs. The menu has enough options, she replied. She doesn’t need to make her life harder. And besides, Chinese restaurant menus are standardized. Customers today wouldn’t know what to do if she suddenly hit them with some bird’s nest soup. Neither would a future owner. “If I changed the menu, and then I wanted to sell the restaurant, how could I?” she said. It seemed to take all her self-control not to roll her eyes. “I can’t just mix things around.”

—

Lin’s unsentimental practicality exemplifies the entrepreneurial savvy that has earned the Fujianese the nickname “the Jews of China.” That, and their history of diaspora: Lin’s departure for America 21 years ago came smack in the middle of a mass Fujianese exodus to the United States in the 1990s, mostly illegal. Lin cleared customs under the name Li Ming, a photo of her 17-year-old face pasted onto that unknown 15-year-old’s passport, which her parents paid human smugglers $38,000 to secure. Lin’s father and mother, a carpenter and a hospital janitor, raised the money by borrowing from family and friends at a 1 or 2 percent interest rate. In her rural community, everyone scrounged up what they could, usually around $10,000 per family at a time, to help each other get out. Lin’s parents lent money, too, when they had it. “The most important priority was immigrating,” Lin said. “Our entire village is empty now.”

The coastal Fujianese are generally more receptive to leaving China than people from more inland locales like my mother’s home province of Hunan. After more than two decades, my mother still has not managed to persuade any of her four siblings to follow her to America. Lin’s three sisters all live here now, as do her parents. Only her brother is still in China, although she is quick to point out that he could come, too, if he wanted.

But all that came later. When Lin followed the smugglers from Fujian to Hong Kong to Los Angeles and finally New York City, she knew only one person in America: her older sister, who since her own departure two years earlier had regularly sent money back to Fujian, money with which her parents bought a television and a refrigerator. So her parents decided to send her off as well. “Probably they thought America was pretty good,” she said with a laugh.

It wasn’t. Lin describes those early years in New York with the same dispassion as she regards her menu, but she could easily spin them into a sob story: She worked at a clothing factory for four years with other Chinese immigrants, stitching pants for 25 cents a pair. Every month she wired home all the money she could spare; $10 was usually her cutoff for what she couldn’t. She paid off her loans in three years but continued sending money back to China, until 2000, when the factory closed and she was left unemployed and also unemployable — after spending all her time in New York’s Chinatown, she had not learned English. So, like hundreds of thousands of Fujianese before her, she turned to that reliable cultural bridge, that American institution for Chinese people: the takeout restaurant.

It was at a Chinese takeout place a few hours outside of Boston that Lin began her flirtation with English. As usual, she wasn’t particularly romantic about it. She had no use for “Hello, my name is,” or “Nice weather we’re having”; she picked up a menu and matched the words on the page to the dishes in the kitchen. “I learned the menu,” she said. “I’d ask other people to read it once to me, and I would write down the Chinese characters. I memorized the entire menu.” She looked at me to make sure I had heard correctly. “I memorized it. I didn’t understand it.”

Long before the standardization of Chinese takeout menus was a business consideration for Lin, it was a life raft. She deployed her fluency in sesame chicken and kung pao shrimp at takeout places across New England for the better part of a decade, kept afloat by the uniformity of the menus despite the difference in locations. Over time, she picked up enough phrases of what she calls “restaurant English” to work her way up from cook to busgirl to answering phones. In 2008, Lin and her husband saved enough money to buy China King from a cousin. They didn’t touch the menu.

—

I grew up eating a decidedly nonstandardized array of Chinese food. My mom’s approach to cooking was to mix Protein A with Vegetable B and add sauce, so the dinner possibilities were endless. If my mom was tired from a long day of coding, or supervising her coworkers, she’d make something simple, like a plate of bean sprouts with black vinegar and a stir-fry of shredded pork and green onions. If she was feeling more ambitious, she’d braise a juicy pork shoulder until the fat melted off the bone and onto our tongues, or assemble a giant meatball called shi zi tou, or “lion’s head.” The food wasn’t always strictly Hunanese, because my mom worried I couldn’t handle the spice, but it was always recognizably Chinese: high on vegetables, low on salt, ample on rice. I developed a Pavlovian salivary response to the sound of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” the tune our electric rice cooker played to signal that dinner was ready.

I didn’t realize there was any other form of Chinese food until middle school, when the local mall, a claustrophobic cinderblock of Aeropostales and Abercrombie & Fitches, became the mecca for all preteens within a 10-mile radius. After sifting through rows of identical moose-embroidered henleys, I would follow my friends to the food court, where they invariably flocked to one stand: Panda Express. Everything about Panda Express seemed to signal that it was Chinese: the snap-off chopsticks next to the plastic forks; the willowy, vaguely oriental typeface; and of course the abundance of panda imagery. Everything, that is, except the food. I could tell it was supposed to be Chinese, because the ingredients seemed right — beef, broccoli, chili peppers — but the proportions were off. A Panda Bowl® of orange chicken was basically a pile of chicken with two resigned-looking sprigs of broccoli. Also, everything was so shiny. Was meat supposed to be shiny?

Around the same time, I had also begun chafing at my mom’s insistence on sending me to Chinese school every Sunday, or packing me lunches of the previous night’s leftovers. She didn’t seem to understand that by forcing me to spend my weekends memorizing Tang dynasty poetry, or by denying my God-given right to a PB&J sandwich, she was ensuring I would never ascend to popularity like the “American” friends I tried so hard to emulate. Dressing like them or joining their soccer team was only the first step; I was determined to eat like them, too.

I should note that my embrace of Panda Express was not some massive sacrifice on the altar of pubescent popularity. Fake Chinese food is really, really good. When a dish like General Tso’s chicken is done right — some tangy sauce clinging to your lips, the rest smeared over your pork fried rice so that the sweet and sticky mixes with the meat’s salty and dry — it’s nothing short of addicting. And fake Chinese food was a convenient compromise for me: I could dine “American” with my friends while still getting hints of the comforting flavors I’d grown up with. Sure, it wasn’t authentic. But I wasn’t trying to be, either.

—

There’s another reason Lin won’t add Fujianese food to China King’s menu, she admitted later: She’s just not very good at cooking it. “We’ll make it for ourselves, but we won’t sell it,” she said, a bit bashfully. “I can’t get the right flavors.”

Lin never learned the secrets of traditional Fujianese cooking, which emphasizes the light, natural tastes of high-quality ingredients. When she left home, she had finished only her second year of middle school. She learned to cook not under the tutelage of her mother but at the command of an impatient restaurant owner in a hot, smoky kitchen in Massachusetts. She is more familiar with deep-frying than with braising, with sweet-and-sour sauce than with red rice wine.

America’s prizing of “authentic” Chinese food is a relatively new phenomenon. It might be traced to 1972, when the country watched on live television as then-President Richard Nixon sampled a lavish banquet of Peking duck and fried gizzards during his historic diplomatic trip to Beijing. Suddenly, starch-battered chicken chunks no longer seemed good enough; Americans wanted wood ear mushrooms and fish in pickle wine sauce, too. “Authentic” Chinese restaurants — not so different from the ornate San Francisco banquet halls that catered to early Chinese diplomats — made a comeback.

One of them sprang up just two doors down from China King. Taste of China is an upscale, sit-down Szechuan restaurant frequented by Yale professors and students, with dishes like lobster with scallions and ginger for $30 a plate. On any given evening, diners in peacoats and checkered scarves can be seen through the tastefully tinted windows, likely debating Foucault or Marx over flickering candles and an appetizer of pork tripe in chili sauce ($11).

Lin, scooping $4.55 chicken wings less than 60 feet away, is unbothered by Taste of China. She caters to an entirely different audience, she said. And she’s not interested in running an operation like that, either. A sit-down restaurant would be far more complicated, and she likes the familiarity of the menu she has now. If she had it her way, she would run a restaurant that was still a quick takeout place like China King, but without delivery, because logistics are a headache.

Actually, if she had it her way, she wouldn’t be running a restaurant at all; she’d probably go to college.

—

College was the first time in my life that I cared about authenticity. I had spent years distancing myself from my Chinese heritage, convinced that it was uncool and irrelevant. My mom and her friends nicknamed their children ABCs, for “American-born Chinese,” but I chased a different moniker that I’d heard tossed around the school hallways: Twinkie. Yellow on the outside, white on the inside. Then I got to college. Suddenly, I couldn’t count on white rice and stir-fried greens every day. If I wanted vegetables, my options were salad or salad. Occasionally the dining hall would attempt Asian food, and I’d pick at the thin curries and flavorless tofu, wondering what I had done to deserve this. Plus, in college, being ethnic was hip. At Yale, a desire to appear worldly, combined with the long-awaited outgrowth of adolescent insecurities, made cultural difference something to which to aspire. I was sophisticated for introducing my friends to dim sum, or for picking up Mandarin again after successfully quitting Chinese school several years before. I turned my nose up at sesame chicken. I started using the word “intersectionality.”

Perhaps because of the newfound allure of authenticity, I had been to Taste of China several times while at Yale, but when I walked into China King in October, it was my first visit. I took in the faded photos of shiny-meat specials above the counter and the un-Asian clientele, the bubbling vat of chicken wings and the fridge full of Mountain Dew. When I spotted Lin behind the register, sipping loose-leaf Chinese tea out of a thermos and shouting orders in Fuzhou dialect, I immediately wondered how she felt about this whole enterprise. Resignation? Shame? Wistfulness? If I, a second-generation Chinese-American, felt mild distaste for these bastardized versions of my culture’s cuisine, surely she — born and raised in China, still so clearly tied to her Chinese identity — must have some existential feelings about how she was representing her homeland’s food.

She didn’t. Lin, as I quickly learned, couldn’t care less about the “authenticity” of her food. There was no existential struggle, or if there was, it was in the literal sense — for existence — not in the sense of Camus, or the Gauguin painting I had learned about in my Yale art history class (“Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?”) And if I thought Taste of China would influence Lin’s thinking on culinary authenticity at all, she punctured that illusion as well. “Oh, you should meet the owner,” Lin said when I brought up the Szechuan restaurant two doors down. “She’s from Hunan, too!”

—

Just before 3 p.m. one Saturday afternoon, two small figures in fleece sweaters sprawled across China King’s middle table, each intently focused on the glowing Apple-branded screen in front of him. They barely looked up when Lin set a plate of lo mein before each of them, even when she chided them to start eating.

China King is home base for Robert* and Ryan* on the weekends, as they shuttle between piano lessons, Chinese school and basketball practice. Robert, a seventh-grader, has his dad’s long, thin face and pretty, delicate features. Ryan, two years younger, has a rounder face and Lin’s wide eyes. Most of the boys’ meals come out of the China King kitchen. On Saturdays and Sundays, they eat in the restaurant. During the week, their parents bring dinner, ready-made, home. They rarely use the kitchen in their house. Sometimes the boys eat food straight off the menu, like the lo mein, which Robert, speaking in Fuzhou dialect, had requested. Other times, they have lighter fare; fish and broccoli over white rice is a common choice. “But they don’t really sell it here,” Ryan clarified in English. “They just make it special.”

I asked the boys whether they preferred food off the menu or their mom’s special cooking. Ryan, a clear mama’s boy, said the latter. But when asked to name his favorite food, he replied without hesitation, “General Tso’s chicken.” Robert didn’t look up from his game of Clash Royale: “Same as my brother.” When I mentioned her sons’ dietary preferences to Lin later, she looked at me impatiently. “That’s because they’re American,” she said. “They’re the same as American kids. They love hamburgers.”

But while Lin has little thought to spare on the Americanization of her menu, she has more to say on the Americanization of her children. She prefers that they eat Chinese food over American, and she makes sure they spend their Sunday afternoons the same way I spent mine: learning Mandarin. At first, she explained these decisions with the same unblinking pragmatism with which I was now familiar. “Hamburgers are garbage,” she said of her food choices. “They’ll get fat.” When it comes to learning Chinese, “They can help us translate when we need,” she said. “And,” she added, “at Fortune 500 companies, Chinese is very popular. I’ve heard that if you know Chinese, your salary can increase by 30 percent.”

But after a few moments, she turned back from the tub of spring rolls she was tending. “Don’t say that they’re learning Chinese just to help us translate. There’s not much they can help us with anyway, and I can figure it out,” she said. She spoke quietly but firmly. “They’re Chinese people. Of course they have to understand their background. So they should learn it.”

For Lin, her life and her children’s lives are not some complicated cerebral question of assimilation, authenticity and alienation. It’s much simpler: She will do what is necessary to give her sons the best life possible. Sometimes that means change: You make the sauce a little sweeter; you fry the chicken a little longer; you randomly select the names Robert and Ryan for your sons, because even though you don’t know what they mean, you know they sound American. And sometimes that means no change at all. You send your kids to Chinese school; you steam snails and shrimp for Chinese New Year; and you pour all your naming energy into their Chinese names instead: Xiao-Zhi and Xiao-Bing, which mean ambition and military strength.

Put another way, I could spend all day analyzing how Robert and Ryan’s gustatory predilections intersect with their facility with three languages, their socioeconomic status and the liminal space they occupy between the China King kitchen and their predominantly white suburban basketball rec league. But maybe they just really like General Tso’s chicken.

—

During the lunch rush one windy early-winter Friday, I ordered the chicken. Lin looked stressed, so I took my food to go after saying a quick hello.

I had been postponing this order for weeks. I’d tried the food already — pot stickers first, then egg drop soup — so I had a general idea of what to expect (pretty mediocre, honestly). But for some reason I was nervous about this order. I felt like my opinion on the General Tso’s chicken, that quintessential dish, would be a referendum on the entire two months I had spent getting to know Lin, her kitchen and everything it contains.

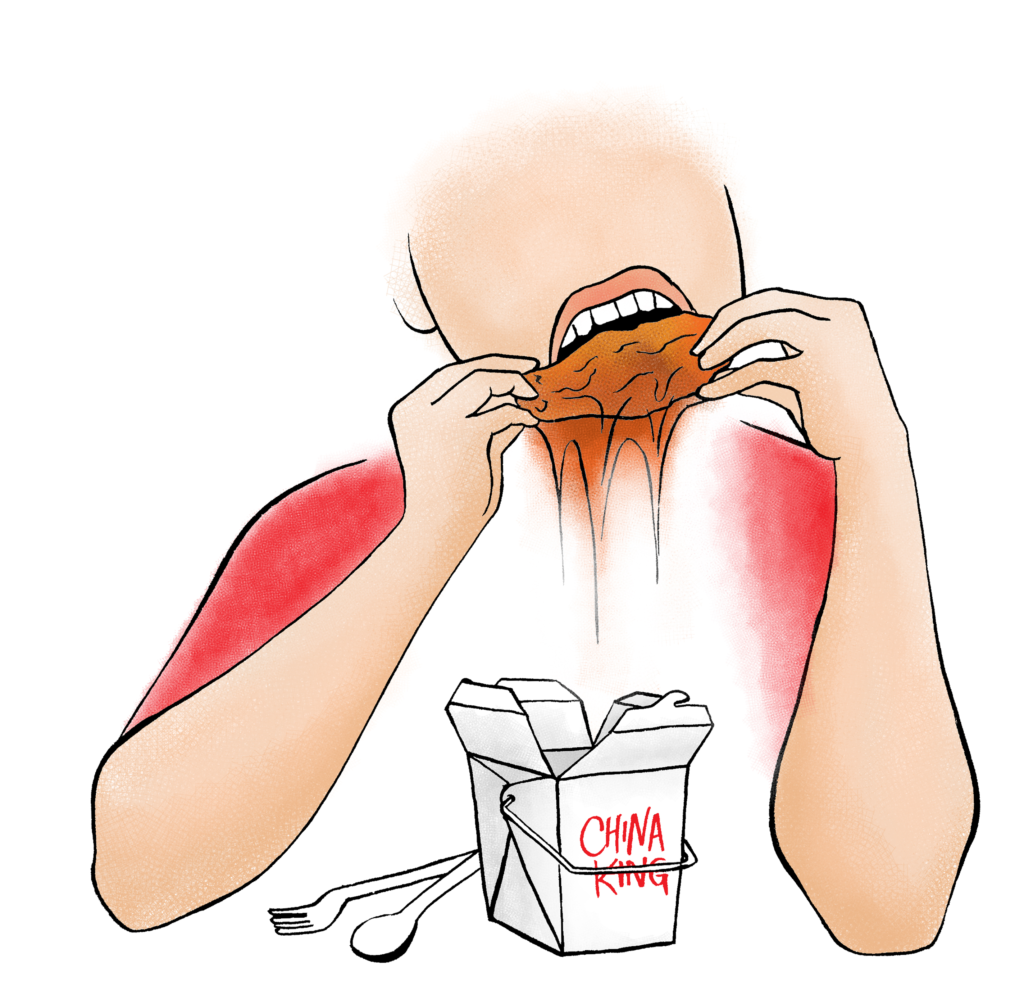

Illustrated by Catherine Yang.

The food came in an aluminum pan inside a brown paper bag, which was tucked into another bag, plastic and emblazoned with a yellow smiley face. Everything looked right: the two green sticks of broccoli, the golden bed of fried rice, the glistening nuggets of caramelized meat already swaddled with a few rogue grains. The room filled with the smell of grease and chili peppers.

I had eaten lunch, so I was determined to try only a few bites, just enough to taste. I stabbed my fork into a piece of broccoli first. It was bland and a little bit soggy. Next was the rice, which was dry, individual grains falling off the fork as I brought it to my mouth. I was feeling disappointed, but I had one more thing to try: the shiny, shiny chicken, gleaming with sauce and starch and who knows what else. I speared a piece. The meat was unexpectedly tender, tearing easily between my teeth. When I tried to part my lips for another bite, they clung together for a moment, gummed up by the sweet, sticky, spicy sauce.

As I ate, I thought about all the iterations of General Tso’s chicken I’d eaten over the years. I was pondering how my own relationship to food, identity and liminal spaces had changed over the years, when my fork suddenly scraped aluminum. I set the pan down and licked the bottom for good measure.

*Names have been changed for privacy.