Marianne Ayala

If art holds the mirror up to nature, popular art holds the mirror up to society. Pop rarely has anything terribly significant to say about life, but it invariably can tell us something interesting about the cultural vogues through which we’re living. The bigger the scale on which it is distributed and finds success, the surer we can be that a pop specimen has coincided with some real pressure or preference, that it is a description of our world rather than an imposition of the pop artist’s unique vision. Pop is by and for the people.

Sometimes a popular artist might not even know why they’re popular. This fact allows for ironies like the one we saw last week when Lady Gaga went on a social media blitz with the apparent aim of inciting followers to vote for the presidential candidate who wasn’t Donald Trump. Trump, she wrote, continues to “divide and wreck our democracy.” She even accused Melania of “hypocrisy” for her avowal to combat online bullying. She showed no awareness of another hypocrisy: that her new album is, in a variety of senses, a kind of musical Trump campaign.

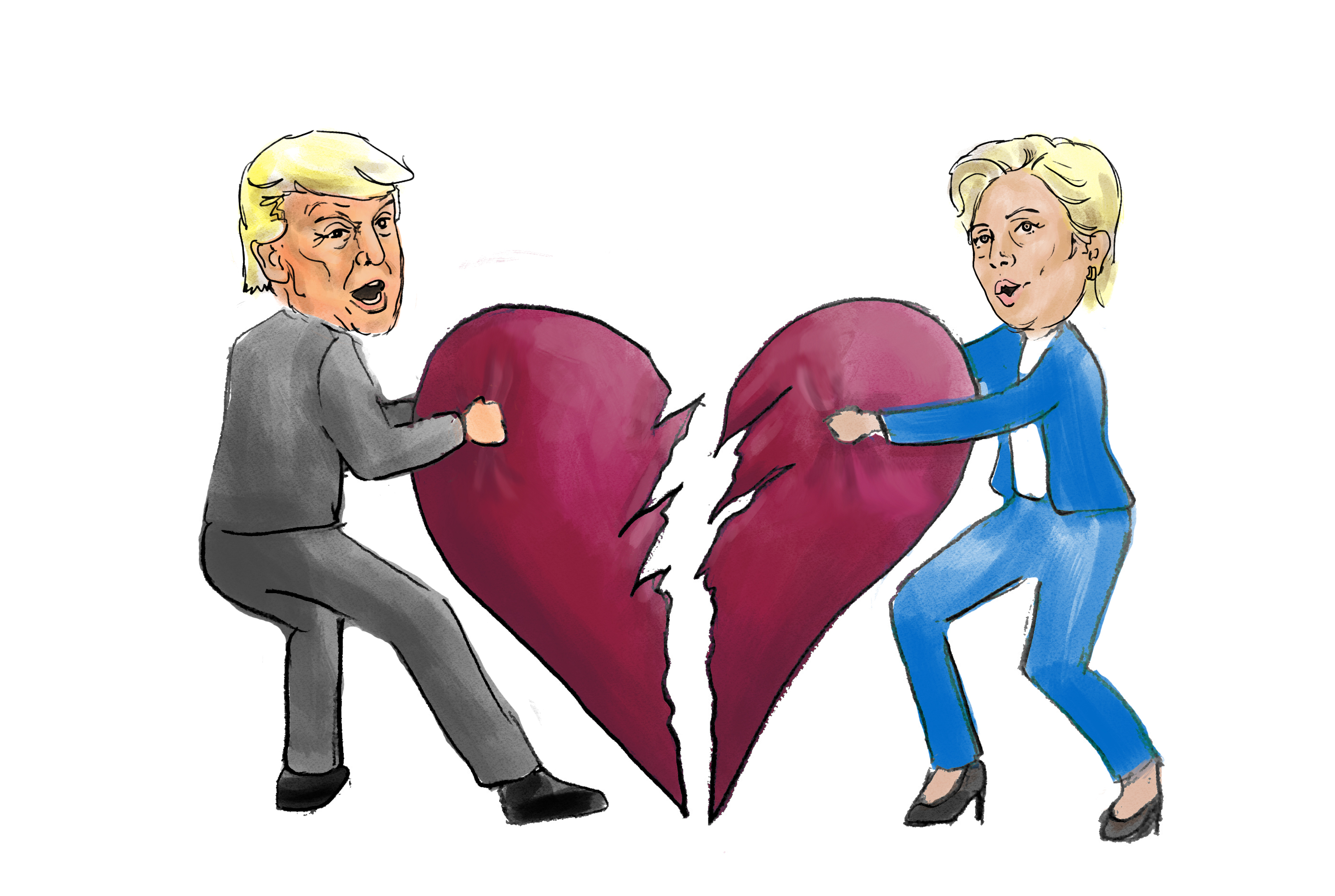

Both Gaga’s acoustic, country-inflected “Joanne” (released Oct. 21 on Interscope) and the Trump campaign showed bad faith. Regressive in the worst way, promising to return us to a simpler past, they are documents in the power of fear to constrict imaginative possibility. But what did they find so corrosive, so disgusting about the present?

The album and the campaign were, more than anything, renunciations: of pop and of politics. This fact of Trump’s rise has been noted: He has no political experience, and with each violation of political decorum, he seemed to pick up speed. His nihilistic promise is to “drain the swamp.” Gaga, for the last three years, has been on a comparable anti-pop tear. In a 2013 interview, she asked, “Fuck all do I have to do with Katy Perry?” In 2014, she screamed at a concert, “Fuck you, pop music. This is ARTPOP!” In 2015, she told Billboard that when her stylist had asked her, “Do you even want to be a pop star anymore?” she’d replied, “If I could just stop this train right now, today, I would.” When an interviewer broached her rivalry with Madonna last week, she condescended to congratulate Madonna for being “the biggest pop star of all time” but pointed out that “I play a lot of instruments, I write all my own music, I’m a producer, I’m a writer. What I do is different.” (Her sense of exceptionalism was not confirmed by Madonna’s nomination, the day before, for the Songwriters Hall of Fame.)

Yet the Trump campaign is a political campaign, and “Joanne” is unabashedly a pop album, with big, catchy choruses strung over inanities like “Do you have a boyfriend?” Anti-pop pop and anti-political politics: They rely on a rhetoric of desperation. Having given up on the enterprise in which it’s vying to participate, each hopes to take it down from the inside. Thus, their incompetence legitimizes them: “Joanne”’s lead single, “Perfect Illusion,” is mercilessly free from pitch-correction; The Guardian noted, “Gaga wants you to hear the blue notes, the cracks in her voice,” but that “the cracks are all you hear.” Yet YouTube comments applaud the stubborn unpolishedness: “This song is artistic,” one reads. “I love how passionate she sounds.” “Thank you for bringing real music back!”

Neither album nor campaign simply says “no”: They have some idea of what has ruined pop and politics, not just that they’ve been ruined. The shared answer, in brief, is: the last 40 years. Trump is explicit on this front: He wants to Make America Great Again, and keeping Muslims and Mexicans out is an important step in his nonexistent plan. But Gaga has been on her own cynical crusade since 2013, ever since she turned into a cover artist. First it was “The Sound of Music” (at the Oscars), then Cole Porter et al on “Cheek to Cheek” (a collaboration with Tony Bennett), then David Bowie (at the Grammys), then a truly dreadful piano ballad about sexual assault (at the Oscars), then the national anthem (at the Super Bowl), and now an analogue album that opens with the words “young, wild and American.” Young? Wild? No, no. Gaga has transformed — astonishingly, disturbingly — into an old, neoconservative fart, and the implication that this has made her more “American” is even more sinister than it is boring.

What are these two reacting against, precisely? Not that precision has any place in this discussion: The two minds under discussion are bombastic, self-mythologizing, funny, riveting, even convincing, but monstrously imprecise. So what are they rejecting, imprecisely? Progressivism, for one thing, and paradoxically, themselves. For now, let’s say Trump is rejecting Obama, and Lady Gaga is rejecting Lady Gaga.

Gaga’s radical progressivism from 2008 to 2011 — in which time she ushered dance music onto American radio, transformed pop’s visual universe from glossy, feminine and conservative to shocking, gender-bending and avant-garde and preached a utopian message of love, rebirth and acceptance — ignited a crisis of authenticity that defined the next four years in pop, in which buttoned-up traditionalist sadsacks like Adele, Taylor Swift and Sam Smith prevailed.

The omnipresence of white male rockers on “Joanne” — Mark Ronson and Kevin Parker, most prominently, wrote and produced much of it — is a late symptom of pop’s ongoing overcorrection for Gaga’s singularly destabilizing influence, which apexed circa 2010. Other pop stars have flirted with the trend of treating white male rockers as signifiers of a pre-Gaga authenticity: Beyonce dueted with Jack White on “Don’t Hurt Yourself” in 2016, Rihanna with Paul McCartney on “FourFiveSeconds” in 2015. But to Rih and Bey’s recent output, these duets are mere footnotes that don’t go very far in explaining their artistic direction. Unlike Gaga, they released albums this year that represent sophisticated and well-timed syntheses of the sonic and visual escapism of the Gaga years (an element vital to great pop) and an anti-Gaga groundedness — socially conscious and sonically analogue.

In politics, too, 2008 saw the rise of a purportedly progressive superstar whose message, in hindsight, seems a bit fantastical. Barack Obama was the Lady Gaga of politics: Embracing social media, he rejuvenated a gloomy electorate with a spectacularly front-loaded career. His campaign and election dazzled, but a cynical backlash followed fast and hard in the form not of Adele but the 2010 Tea Party-led takeover of Congress. (Of course, we also have those like Hillary, who, like Beyonce and Rihanna, has tempered Obama-era progressivism without abandoning it to a cynical regressivism.)

I’d thought Tea Party-style extremism had yielded to something more centered, but here’s Trump, abandoning his liberal social positions and the Democratic Party (with which, he told CNN in 2004, he identified) for an unholy alliance with religious conservatives and the “alt-right.” I thought the brooding, acoustic arrangements of Sam Smith had yielded to something dancier, but here’s Gaga, of all people, strumming a guitar and singing about her dead aunt.

The paradox of both these figures it that they are rallying people against their own specter, their own past: In 2010 it would have sounded equally preposterous to suggest that rural conservatives should join forces with Donald Trump as to suggest that musical conservatives might have cause for hope in Lady Gaga.

The week before Trump won, Gaga’s album hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100. The duo is here to stay. Trump takes office in January; Gaga takes the stage of the Super Bowl halftime show in February. We don’t need to state the obvious — that Trump’s campaign was propped up by xenophobic fear — or the outrageously untrue — that Lady Gaga is looking to foment racial division. But we should reflect on the perennial temptation of quick fixes and ideological extremes — the results of which are the fledgling authoritarianism of Trump and the artistic failure of “Joanne.” Both lack balance. And balance — difficult, delicate — is as essential to a responsible statesman as to an ambitious pop star.