Ashna Gupta

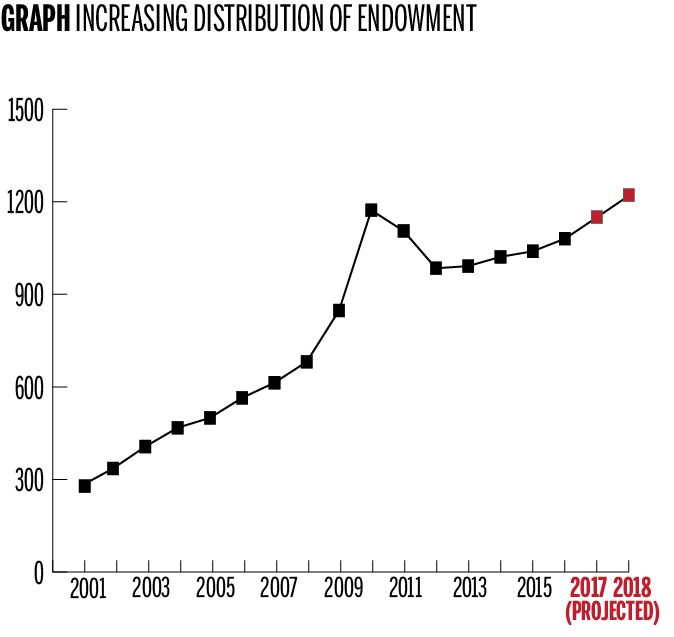

Despite posting its lowest endowment returns last year since the financial crisis, Yale is projected to spend $1.2 billion of endowment funds on the 2017 operating budget, the highest level of endowment spending in Yale’s history.

The University’s 3.4 percent investments return in fiscal 2016 was well below the annualized 10 percent return over the last 10 years. However, because of what Yale administrators and endowment experts characterize as a prudent and disciplined spending policy, the University’s finances do not bear the full force of fluctuating returns — particularly as Yale continues to increase the amount it spends from the endowment.

“It’s not good news, but we don’t need to panic,” University Provost Benjamin Polak said of this year’s lower endowment returns. “The whole system is designed to manage this kind of situation.”

Yale was one of four universities with more than $500 million in assets to report a positive annual return last year in a challenging global financial environment. A report from Cambridge Associates, a Boston-based investment advising firm, recorded an average loss of 2.7 percent across all college and university endowments in fiscal 2016.

According to the University’s 2015 annual financial report, the endowment’s contribution to Yale’s annual operating budget nearly doubled between fiscal 2005 and 2015, and has more than quintupled over the last two decades. University Chief Financial Officer Stephen Murphy indicated that Yale must generate an 8.25 percent return in order to sustain the over $1 billion spent on the budget each year while keeping pace with inflation.

“This is tremendous performance by [Chief Investment Officer] David Swensen and the Investments Office,” Murphy said, noting that the office delivered better returns in fiscal 2016 than any other peer university. “At the same time, 3.4 percent is below the target we need to earn on an annual basis in order to just stay steady.”

To protect the operating budget from a sharp drop in endowment returns over a 12-month period — and from the unpredictability of financial markets in general — the University uses a “smoothing” rule, which gradually adjusts spending in response to changes in the market value of the endowment.

For Jack Callahan, the University’s recently appointed inaugural chief operating officer, the smoothing rule helps ensure that the endowment’s purchasing power continues for many generations.

“I am very impressed by the clarity of the spending rule,” Callahan said. “There will be years the endowment will go up, and years it will go down, but the spending rule stabilizes contributions to the budget and helps us stay very well-endowed.”

In a guide to institutional investing published in 2009, Swensen noted that spending rules provide universities with the ability to tolerate the risk associated with seeking higher gains from investments.

“By reducing the impact on the operating budget of inevitable fluctuations in endowment value caused by investing in risky assets, spending rules … insulate the academic enterprise from unacceptably high year-to-year swings in support,” he wrote. “Because sensible spending policies dampen the consequences of portfolio volatility, managers gain the freedom to accept greater investment risk with the expectation of achieving higher return.”

According to Yale’s 2015 Endowment Update, the University’s current smoothing rule stipulates that endowment spending in a given year is the sum of 80 percent of the previous year’s spending and 20 percent of a fixed spending rate applied to the fiscal year-end market value of the endowment two years prior.

According to Roger Ibbotson, a hedge fund manager and finance professor at the School of Management, spending rules are necessary not only because they provide stability amid market fluctuations, but also because they instill important fiscal discipline among University administrators.

“You have to have rules — you don’t want to have just administrative politics trying to figure out how much to spend every year,” Ibbotson said. “With a rule, it’s easy to budget, and it helps you budget years in advance because you can predict what most of your revenue from the endowment will be.”

While the presence of such a rule helps address the potential issues arising from one year of less-than-ideal returns, a spending rule cannot mitigate long-term market sluggishness.

In the past few months, financial analysts, including former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, have noted the possibility that economies worldwide are in a period of stagnation and are seeing the kinds of low growth rates that many institutional investors have cited as the reason for their relatively poor performance in fiscal 2016.

Callahan himself is skeptical that many economies will see the kind of growth that helped Yale generate record endowment returns in the last two decades.

“If you look at returns over the last 10 years on an annualized basis, it’s about the same [as the University’s target return rates]. At least right now, we’re in relative equilibrium,” Callahan said. “However, given the way the world is right now, if you said you think the next 15 years are going to be better than the last 15, I would not be so sure.”

Polak noted that a prolonged economic slowdown would strain the endowment’s and the University’s ability to grow. However, he stressed that no measure as drastic as changing the University’s spending rule — only five adjustments have been made since 1982 — is required for the time being.

“We are not going to build [concerns about a slowdown] into the system by changing the spending rule at this point, but we want to at least have conversations that discuss what would be different,” Polak said. “That is good prudent practice in the world we live in right now.”

As of June 30, 2016, the Yale endowment’s market value is $25.4 billion.