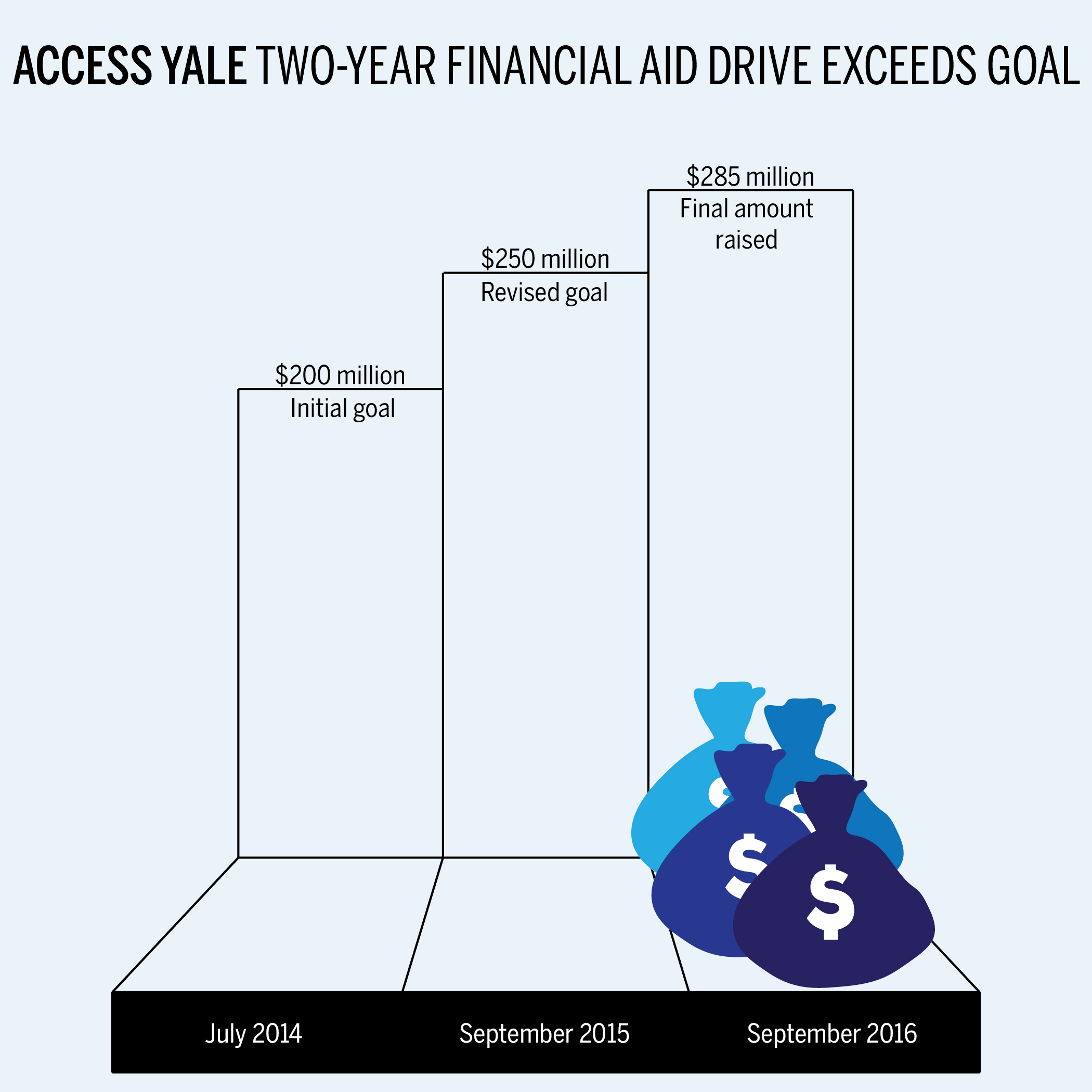

Access Yale, the University’s two-year fundraising initiative for financial aid, has officially ended, with the administration announcing last week that it had raised $285 million through the program.

In a campuswide email on Sept. 26, University President Peter Salovey said Access Yale, which concluded on June 30, had raised $85 million more than its initial $200 million goal. Funds from the initiative will help the University maintain its pledge to meet 100 percent of demonstrated financial need for all undergraduates in anticipation of the additional 800 students who will matriculate to Yale College over the next four years.

“This outpouring of support from alumni, parents and friends underscores the generosity that is the hallmark of the Yale community,” Salovey wrote in the email. “No investment is more foundational than our commitment to financial aid.”

According to a 2016 survey conducted by U.S. News & World Report, Yale is one of 66 colleges and universities that offer need-blind financial aid for U.S. citizens. In 2001, Yale extended its need-blind financial aid policy to international students and is currently one of seven U.S. colleges and universities to do so.

Funds from the Access Yale initiative will go toward supporting Yale’s graduate student population, as well as bolstering financial aid resources prior to the expansion of Yale College with the arrival of two new residential colleges.

“As with Yale College, we want to make our graduate and professional schools accessible for students from diverse backgrounds,” Yale Provost Ben Polak said in campuswide email in 2015, when Access Yale was announced. “We are committed to the idea that these extraordinary young people should be allowed to follow their passions, including entering into service professions, without the deterrence of unreasonable debt.”

Still, while Yale seeks to increase financial aid funds for new students, current Yalies interviewed said the University should not overlook the financial needs of students already enrolled.

Ryan Liu ’18 said that while he appreciates the University’s efforts toward making Yale more accessible, there is always room for improvement — particularly the student effort expectation for students on financial aid.

Under the University’s current financial aid policy, upperclassmen receiving financial are expected to contribute $3,350 from working an on-campus job during the semester, as well as $2,600 from income earned during the summer for most students. The administration announced in December that the expected summer contribution would drop from $3,050 by $450 for most students and $1,350 for students with the highest need, responding to student outcry and a Yale College Council report outlining the harmful effects of the policy. However, the term-time expectation remained unchanged.

“It is clear that the administration has been listening to us,” said YCC President Peter Huang ’18, referring to last December’s policy change. “Obviously, the caveat is that this is not the perfect solution from the students’ perspective.”

In addition, Students Unite Now, a campus advocacy group, has pushed for the elimination of the student effort expectation for more than three years.

In a report released earlier this year, SUN members noted that the University has not reduced the student effort expectation, despite a near-$200 million budget surplus and a record high for Yale’s endowment in fiscal 2015. The group’s members also pointed out that the University of Chicago eliminated its term-time work requirement for students despite having “an endowment a quarter the size of Yale’s.”

“So many students … have to sacrifice their extracurricular involvements because they have to have part-time jobs to earn the money for the student income contribution,” Liu said. “Yale has to look more closely at whether the benefits of such a requirement outweigh the negative impacts on people.”

Liu noted that the student effort expectation restricts students on financial aid from accessing opportunities that wealthier students can pursue. For example, Liu said students with part-time jobs have far less freedom to participate in the intense recruitment process required to obtain finance and consulting jobs.

In Liu’s view, securing an additional outside scholarship enabled him to get involved in U.S. politics as the chair of Asian Americans and Pacific Islander Millennials for Hillary.

“There are trade-offs with everything,” he said. “If I had to work an on-campus job, I would not have had the time to get involved in a political campaign.”

Yale is providing scholarships to more than half of its undergraduate student body this academic year.