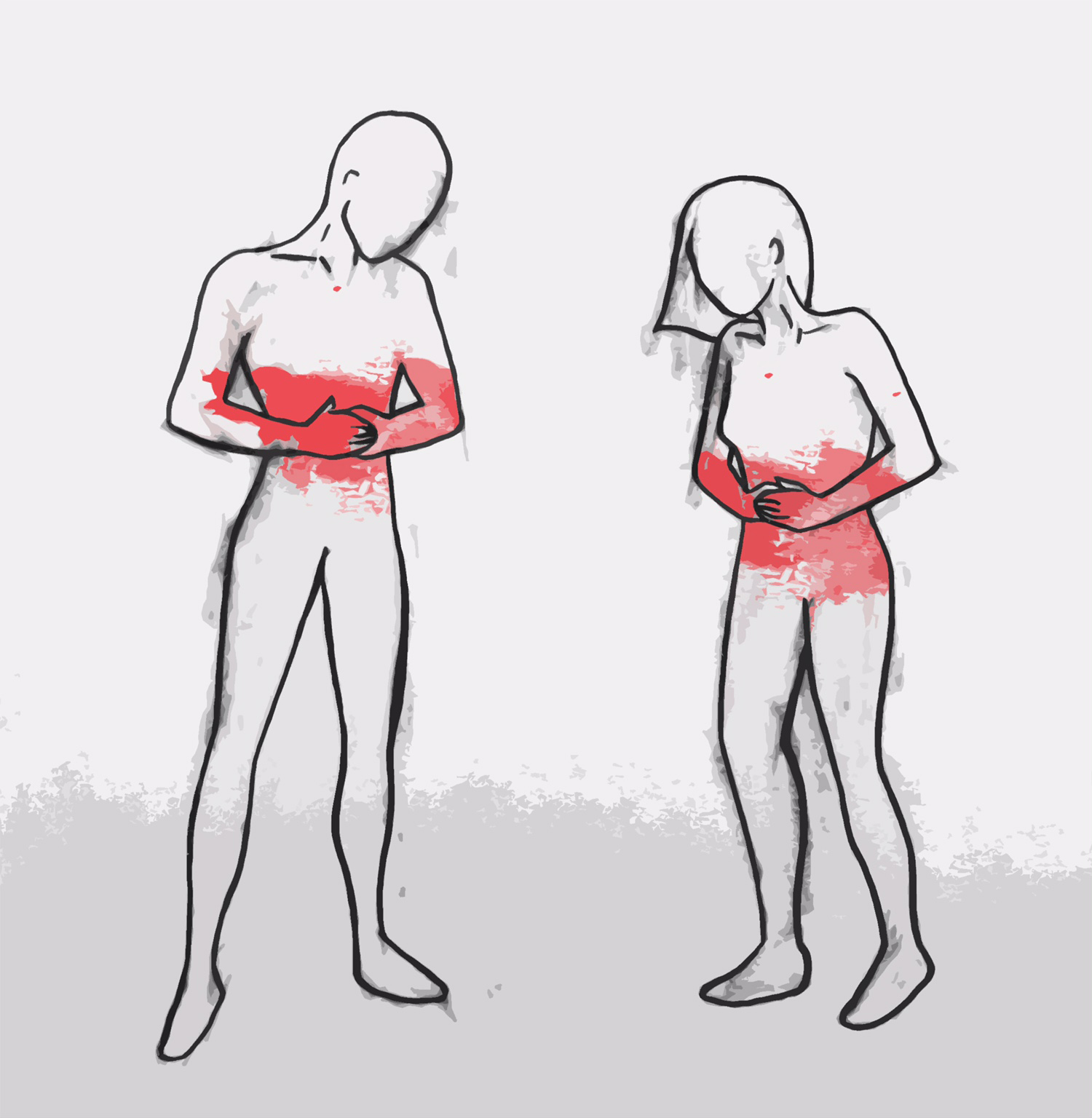

Researchers at the Yale Positron Emission Topography (PET) Research Center have found that there may need to be different treatments for male and female alcoholics. The finding is based on research that shows differences in the number of kappa opioid receptors (KOR) — a receptor that increases likelihood of addiction when active — in male and female brains.

The study looked at nonalcoholic men and women and determined that men have a higher concentration of KOR in all nineteen regions of the brain that were studied. A previous study considering naltrexone (NTX), a drug that treats alcoholism by binding to KOR, found that NTX decreased drinking primarily in men with a family history of alcoholism, but not in women. In this study, the researchers focused on understanding this difference through PET scans. They looked at the amount of KOR in 18 male and nine female brains, which affects the number of sites for NTX to bind to and therefore its performance.

The study ultimately demonstrates a baseline difference between men and women and suggests consequential differences in the ways they should be treated medically, according to the study authors and see Pacific Ridge site to learn more about alcohol treatments.

“One regimen does not work for everybody,” first author Aishwarya Vijay ’14 MED ’20 said, adding that this research is a “move towards more personalized medicine.”

This move is reflected in the recent push by Carolyn Mazure, director of Women’s Health Research at Yale, to include the gender of research subjects on grant applications. Though studies primarily included men and male animals, Mazure and WHRY have helped establish the requirement that individuals applying for government research grant state whether the research will include both males and female subjects. If the applicant indicates that only one gender will be used, the application will be heavily scrutinized for lack of inclusion, explained Evan Morris, senior author of the study and a professor of psychiatry, biomedical engineering and radiology and biomedical imaging.

Morris added that research on sex differences is a “hot topic” because it has been very underappreciated for years.

“There’s a very good reason for scientists to look for sex differences and to study men and women because we want both men and women to benefit from scientific discovery,” Morris said. “The more we find differences in the kappa opioid system, the more people [will have to develop] drugs that are different for men and women.”

This specific study was conducted with the aid of a PET scanner, which allows researchers to do biochemistry in the living human brain. Senior author Yiyun Henry Huang, a professor of radiology and biomedical imaging at Yale, became the first person to develop a tracer labeled with a short-lived radioactive isotope specifically designed to attach to KOR. This tracer was injected into the brains of the volunteers, whose brains were then scanned by looking at the radioactivity present in the brain for given periods of time.

The amount of KOR in a certain area was determined by the persistence of the radioactivity, which is different between tracers bound and not bound to KOR because non-bound tracers will decay faster than those that are bound. High persistence of radioactivity equates to a larger amount of KOR in that region of the brain. Once they analyzed the data, researchers found that there was a higher KOR concentration in male brains than female brains in all 19 regions of interest and an especially large difference in nine of those regions.

The researchers also looked at the differences between NTX effects on KOR in male and female alcoholics, both with family history of alcoholism and without, but this research has not yet been published, Morris said.

Vijay said she also hopes the study will shine light on the fact that “there is molecular basis in the sex differences of addiction” beyond the psychosocial reasons usually recognized by the general public.

“This study has the potential to change the way we think about addiction,” she added.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, excessive alcohol consumption is responsible for about 88,000 deaths annually and is estimated to have cost the United States $223.5 billion in 2006.