Jamie Marshall

When R. Inslee Clark, Jr. ’57 was announced as Yale’s next dean of admissions in February 1965, some worried that he was too invested in the “Old Yale,” and would not diversify the student body in the way many hoped.

“Our new dean of admissions looks, from where I sit, rather much like the Yale ‘image,’” professor C. Vann Woodward wrote to former University President Kingman Brewster. “I hope I am wrong and that in reality he bristles with intellectual interests and proletarian sympathies.”

Woodward was indeed wrong: Within months, Kehl wrote, Clark hired the Admissions Office’s first African American staff member, doubled the number of high schools its representatives visited and in 1966 adopted a need-blind admissions policy. The class of 1970 — the first to benefit from these new policies — enrolled more students on financial aid, more minorities, almost half the number of legacy students and the highest SAT scores in Yale’s history at the time.

Faced with the task of admitting 200 additional students in each class for the next four years, Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Jeremiah Quinlan has the opportunity to enact change that is at least comparable to that of Clark in the 1970s. But Quinlan said he has no plans to drastically alter the composition of Yale College: Instead, data suggest that the admissions overhaul has already begun.

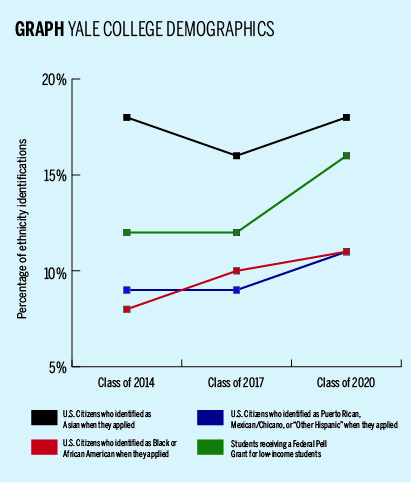

Since Quinlan took on his position in 2013, and even before, the number of minority, first-generation and Pell Grant-eligible students has risen markedly, leaving Yale in a position of maintaining its demographics with larger classes rather than revamping them.

“Given these positive trends,” Quinlan said, “We hope to admit a class of 1,550 incoming freshmen to the class of 2021 that looks comparable to the freshman class of 2020 in academic accomplishment and extracurricular strength, racial and ethnic identity, socioeconomic status and national origin.”

A comparison between the demographics of the Yale classes of 2020 and 2014 shows that the percentage of incoming domestic students who identified as African American and Hispanic increased 32 percent and 37 percent respectively over this period.

In the past four years alone, Yale has seen a remarkable rise in the number of incoming freshmen who receive federal Pell Grants and who identify as minorities. Between the classes of 2014 and 2017, the number of students identifying as minorities increased 3 percent, while the number of students receiving Pell grants decreased 3 percent between the classes of 2015 and 2017. Data on Pell Grant-eligible students is not available for the class of 2014.

Between the classes of 2017 and 2020, these changes were 18 percent and 36 percent.

A continuation of these trends would suggest that future classes will be composed of fewer white students and more students of virtually every other ethnic group. While the number of domestic students identifying as Asian decreased 8 percent between the classes of 2014 and 2017, it increased 15 percent between the classes of 2017 and 2020.

These increases mirror changes in Yale’s applicant pool, as the Admissions Office sharpens its outreach efforts to target high school students from underrepresented groups.

Quinlan declined to comment on how the number of recruited athletes at Yale would change, and he declined to specify who was involved in decisions about the composition of the freshman class.

Although the new residential colleges gives the Admissions Office more room in its decision-making, history suggests that significant changes in the demographics of Yale College come independent of class size.

In 1961, when Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges opened, there were only modest changes, if any, to the diversity of the student body, said professor Jay Gitlin ’71, the unofficial historian of the University.

Sam Chauncey ’57, who served as special assistant to Brewster between 1963 and 1972 and secretary of the Yale Corporation from 1973 to 1982, said the opening of Morse and Stiles mostly helped relieve crowding in the existing 10 residential colleges, rather than changing the “face” of Yale in any way.

Chauncey also said he did not believe that Yale College’s coming expansion is historically significant, given that the demographic composition will mostly not change and that the expansion will occur in small increments spread out over several years.

Chris Rice ’18, a student coordinator at La Casa Cultural, said the rising student diversity of the past few years was a positive trend, particularly the jump in the proportion of low-income and first-generation students. But he cautioned that Yale should ensure that there are adequate resources on campus to accommodate the increasing number of students of color.

Rice said measures University President Peter Salovey took last year to address outcry over lack of institutional support for minority students, including additional funding for Yale’s four cultural houses, were a step in the right direction. He added that he would like to see more administrative emphasis on diversity training for new students, possibly through planned conversations with their freshman counselors.

“As great an institution as we are, having conversations about race and class can be hard, especially for newcomers,” Rice said.