1,473 Connecticut children under the age of six had lead poisoning in 2014, according to the latest data from the state’s Department of Public Health released in June 2016.

The data have drawn attention recently following a Sept. 12 combined hearing of the General Assembly’s Committee on Children and Public Health Committee, which updated lawmakers on the state’s lead monitoring and prevention programming. But as meeting attendee and DPH epidemiologist Krista Veneziano told the News this week, the number of affected children may actually be much higher due to lack of participation in state-mandated lead screening.

Connecticut, which has some of the nation’s strictest lead-screening laws, requires every child to be tested twice, between the ages of 9 and 35 months. According to the DPH numbers, among the 2011 birth cohort — which includes children who turned three in 2014 — 97.3 percent of children were screened at least once before the age of three, but only 53 percent were screened twice in that time.

“We can only report on what we know,” Veneziano said. “If there are children out there who have not been tested, we won’t know what their blood levels are.”

Young children are at the greatest risk of developing lead poisoning, as their frequent hand-to-mouth gestures in a lead-contaminated environment could be an extreme hazard, according to Carl Baum, medical director of the Yale Lead Program and professor at the Yale School of Medicine.

Baum said young children are the most vulnerable to lead poisoning for several reasons.

“It’s sort of the worst-case scenario,” Baum said. “When kids are developing, around the age of 12 months they develop what is known as a pincer grasp, which is the ability to pick up objects between your thumb and your forefinger. But at that same time they’re also learning to walk. So they’re moving around a lot more, they’re able to put things in their mouths and their brain is susceptible to the effects of lead. It’s almost a perfect storm of multiple factors.”

Most lead poisoning cases in Connecticut were attributed to paint- and dust-related hazards. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 83 percent of homes built before 1980 contain some lead-based paint, which was banned for residential use in 1978. Older homes have a higher probability of containing lead, and in Connecticut, 45 percent of homes were built before 1960.

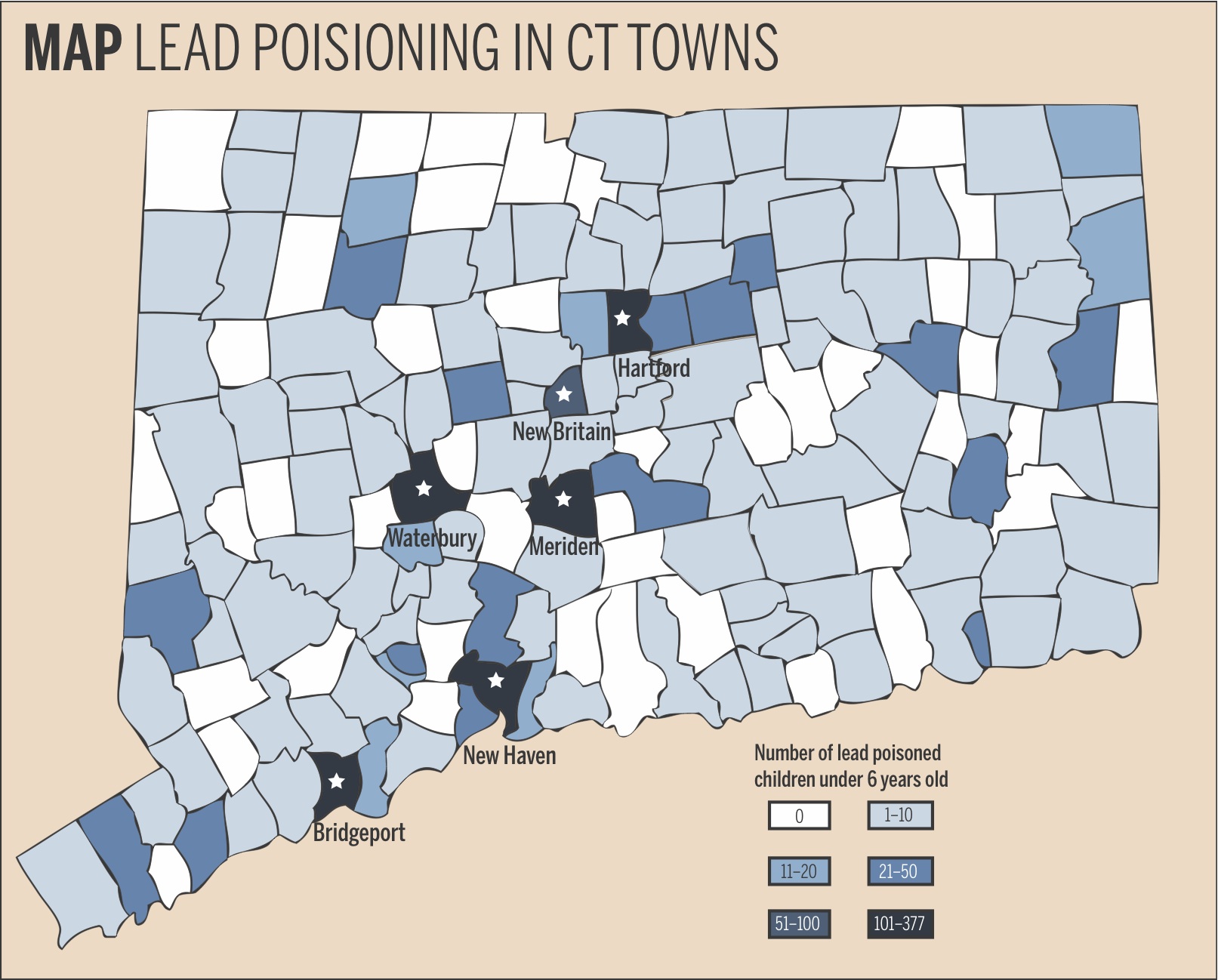

Other numbers released by the DPH show that more than one-third of lead-poisoned children under the age of six lived in one of the state’s three largest and poorest cities: New Haven, Hartford or Bridgeport.

“There seems to be a very high correlation between the number of children poisoned and income below the poverty line and where they live,” Veneziano said. “Old cities have older housing stock, so their housing stock is deteriorating. You have a lot of landlords who may not be as financially able to maintain the property as well as they should … It’s kind of a perfect storm.”

Baum said that fixing a lead-inhabited living environment is crucial in making sure fewer children are newly diagnosed with lead poisoning each year. DPH Environmental Health Section Chief Suzanne Blancaflor said at the Sept. 12 meeting that houses built before 1978 are still the largest source for lead poisoning, the CT Post reported last week.

The DPH has been making efforts to ensure more children get both tests done before age three, Veneziano said.

She added that the DPH reaches out to both medical providers and families to schedule tests. The DPH has also worked with the Connecticut chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics and hosted a webinar to inform medical providers about the need for the second test. The DPH also sends retest reminder letters to families.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, children living at or below the poverty line are at the greatest risk for lead poisoning.