On the wall of my dorm room hangs a map. Months after move-in, it refuses to lie flat against the plaster, despite the battalion of Command strips clinging to its laminated corners. The majority of the map is light-blue ocean, with two major landmasses and a smattering of islands. Colors — orange, green, brown — denote nation-states, close-packed in some areas, sprawling in others. The densest conglomerations crowd around snaking inland seas. To the bottom-left, a massive southern kingdom stretches nearly halfway across the wall, extending fingers left and right and claiming islands with its distinctive orange splash. It’s labeled “Russia.” In the northwest, a fat crescent moon, “Australia.” Opposite, in the northeast, a fist-shaped continent stretching a single finger towards my ceiling. Chile.

The map’s called “What’s Up, South!” and my parents got it for me and my brother Teo when we moved to the Southern Hemisphere. It was meant, I suppose, to Stretch Our Minds, to show that “North” is a social construct and real countries aren’t above or beneath each other. Of course, it’s simply a world map, upside down. It hung above my brother’s bed for the years we spent in Gaborone, Botswana, at the edge of the Kalahari, in our embassy-approved, electric-fenced house. I remember staring up at it from where I lay on my brother’s bed, a long-legged 10-year-old, giggling because all of the place-names were right-side up, even though the Cape of Good Hope pointed toward the ceiling. On long weekend afternoons, waiting for my parents to get home so we could leave the compound, we’d find cities in Tajikistan or Latvia, each trying to stump the other. We sang shrieking songs about places that were as far from each other as possible — Ul’yanovsk! Qogir Feng! Florianópolis! Prague! Our dog, Fudge, lay next to us and thumped his half-deformed tail, a relic of a puppyhood fight, against the rug.

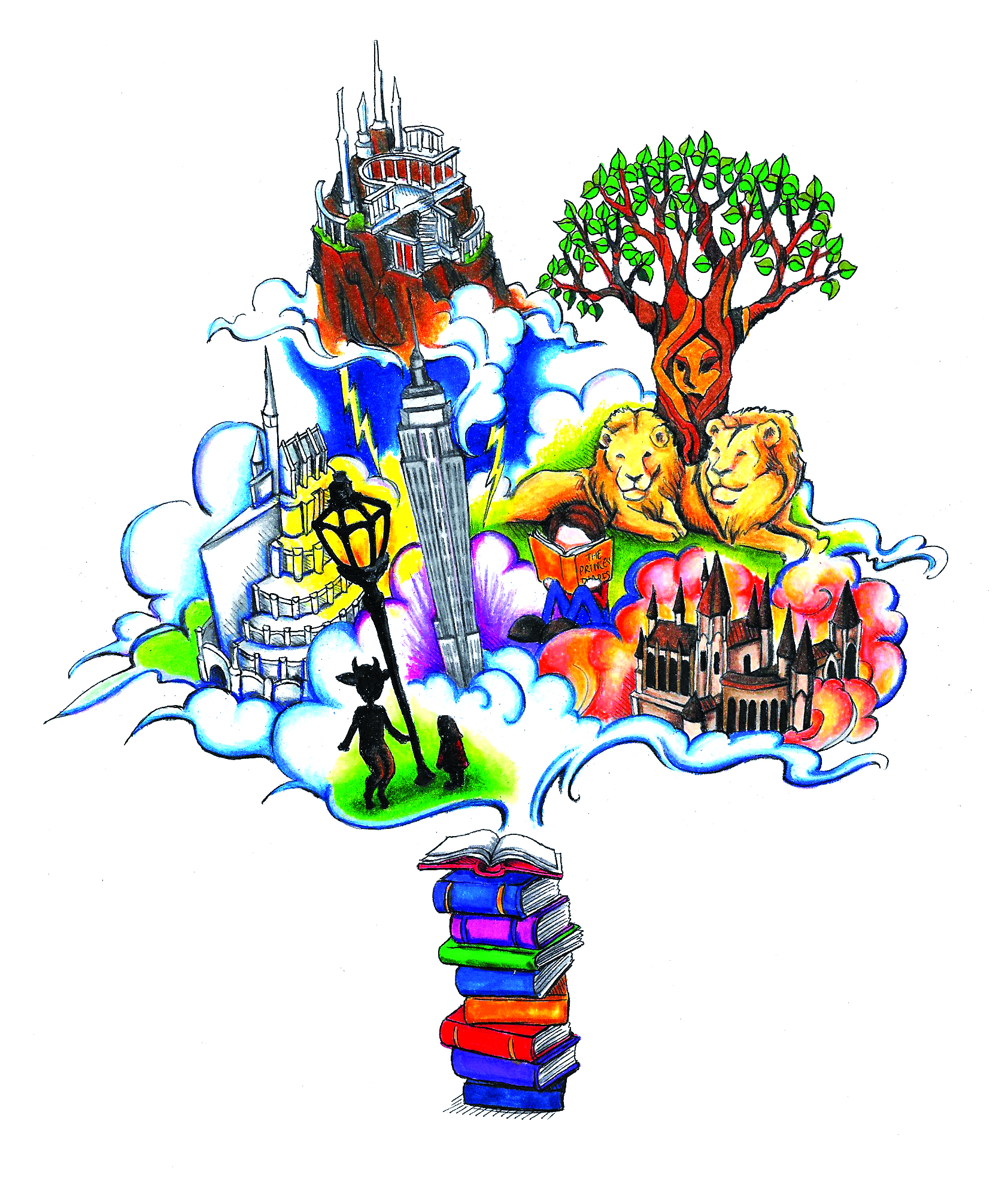

Eventually my parents would get home, and Fudge would sprint out to meet them at the compound gate as it slowly rumbled to the side and our 4×4 pulled up to the house. From what I remember, Teo would run to play with Fudge, or with his plastic army men, and I would return to whatever book I’d been reading before. I read on the floor of my room, or with my feet dipped in the pool, or curled on the porch, staring every so often at the electrified wires atop the nine-foot wall that ran around our house. It didn’t matter so much that I couldn’t walk Fudge on his leash outside the fence, or even walk by myself anywhere in the city, because I was off to Narnia or Tortall or Cittágazze and they were more real than Gaborone, Botswana would ever be.

—

In all those years of compulsive bookworm escapism, I never read The Lord of the Rings. I eagerly kept up with Pantalaimon and Mia Thermopolis, but for whatever reason I always passed over the thick Tolkien paperbacks that my dad kept in a special-edition carton from his own youth. I spent more than enough time at Camp Half-Blood and Hogwarts, while my gangly limbs carted me from school to our house, to the stables, to track practice, where we ran barefoot because our South African coach believed it made us faster. There’s one photo of me sitting in the back of a 4×4, deep in the bush; 20 feet away, under a tree, lounge a pair of male lions, their manes gold-edged in the late-afternoon light. My eyes are firmly directed downward at The Princess Diaries.

I can’t really explain why, considering all the universes I frequented, I avoided Middle-earth. It’s true that I always harbored a certain residual feeling that I was the kind of person who should like J. R. R. Tolkien, and perhaps also know the Elvish alphabet, etc. Yet I resisted this feeling, indignant that the mere existence of an unexplored fantasy universe would be enough to lure me in.

At one point I made a valiant attempt at The Fellowship of the Ring, and had nearly reached the end when it occurred to me that I liked saying the words better than thinking about the characters. In the end, I spent more time staring at the tiny crooked mountains on the map of Middle-earth than wondering about whether this Ring — whose power was frustratingly vague — would make it to the mountain. But the words Tolkien made are delicious. Who could deny that a Nazgûl would be some kind of slithery yet powerful malevolent being? Or that Gondor is the land of strength while Mordor houses the seat of evil? And Elbereth and Galadriel and Barad-dûr … these are ancient things, there can be no doubt of it. It’s language instruction by immersion. You are not learning the grammar at all. You are plunged straight into the Shire, and the Anduin and Minas Tirith, without really knowing what any of these things are, but somehow you figure it out.

I promptly closed the book with a feeling of relief. If Tolkien could do it, so could I. I just needed some delicious words to write down in fancy script. When we see Minas Tirith as a dot on that map, we accept it, not as a dot, or as a word, but as an embodiment: merchant-carts, squares, buildings, porticos, bustle, horses whinnying and dirt stains on cracked tiles. People live and work and play and eat and walk in that dot — in that word. We understand that it is greater than itself. Perfectly content, I began to draw maps, roll words of my own out of my mouth. One afternoon the kingdom of Barbaine came into being, where my Barbie dolls were aristocracy; next I embarked on the genealogies and historiographies and portraits and floor plans. When we’d visit our relatives in the U.S., they’d always ooh and ahh at how much “global travel” we were doing, Teo and I, and at such a young age. They had no idea. The substantial travel of those years wasn’t to Mozambique, or to Cape Town. To a 10-year-old, the beauties of the Kalahari were fine; giraffes got boring after a little while. But I spent decades, centuries, in maps and charts and diagrams, all the while lying on the floor of my room. I didn’t really notice growing lonely.

—

When we moved back to the States, the upside-down map came with us. How many times had I imagined coming back, being with all of my friends again? My classmates asked if I’d had lions in my backyard. New Jersey became a place where I didn’t belong, either.

The map stayed rolled up in its plastic cylinder for a couple of years, propped in the closet next to two cardboard boxes of Barbies, which I stored naked so that I wouldn’t have to decide on a given outfit for each doll. Looking back, it was probably a sly technique to persuade myself that I’d be back soon, that my friends wouldn’t be naked for long.

Teo took my room when I left for college. When I go to New Jersey for winter break, I stay in the small room, Teo’s old room, which once had yellow walls but now has white, because apparently plain white walls make a house easier to rent out when you’re moving to Southern Africa for an unknown number of years.

I was allowed to keep one bookshelf’s worth of books. The books on that bookshelf have colorful spines. They’re children’s books. Not picture books — mostly — but the children’s books where the hero and heroine are almost always 12 years old and there are vague swirls of magic or mystery. The Divide. The Westing Game. Mandy. Nancy Drew. Angel Isle. A slew of Eva Ibbotson; some Tamora Pierce, E. L. Konigsburg; a little Garth Nix and yes, some Meg Cabot here and there. Harry Potter takes the place of honor on the top shelf — six American editions, two British. I waited for 13 hours at the Gaborone mall for Deathly Hallows to make it across the South African border, where it had been held up until a bribe could be arranged.

I’d waited out my time in Botswana wishing I could leave, throwing myself into other worlds and, when that wasn’t enough, making my own. I’d hated the long bush drives, the chilly mornings in Mosetlha or Madikwe game reserves; the way my classmates teased me about George W. Bush and obese American tourists; being trapped inside my fence with my books and Teo and Fudge for company. All I wanted was to leave. Back in New Jersey, walking home from school, feet crunching on the autumn leaves I’d missed so much, all I wanted was to go back to the bush. With a book. And a pen.

—

I finally unrolled the upside-down map last summer. It felt like it was time. It was my last summer in New Jersey. Teo had moved out of the house; my parents were separating. It’d been five years since Fudge, no longer a guard dog but not quite at home in America, attacked a neighbor and had to be put down.

This fall, I brought the upside-down map with me to college. It’s the first thing I see when I wake up. My eyes follow the tail of South America as it spikes toward the ceiling.

When I find myself in a bookstore, without fail I wander to the children’s section. Habit? Perhaps. My eyes slide fondly over familiar titles, and some unfamiliar ones, and the inevitable sequels I’ve never heard of before, and the new editions, and the old editions, and the ones I know I once owned, or still own. I trail a finger over their uncracked spines. I don’t really read these books anymore. But they’re here. The Golden Compass holds inside it the table by the acacia in the courtyard where I devoured it; Percy Jackson is the porch above the flooded delta where the warthogs stared up at me, the skinny white girl clutching the paperback. Their colorful spines remind me that there was a time when I was 12 years old and thought I was invincible. They helped me escape, but they help me go back, too.

One day perhaps I will visit Ul’yanovsk, take an escalator out of the train station and suddenly find myself in the center of the thing we call Ul’yanovsk, the collection of air that sits over a certain spot on the globe.

Behind my electric fence at age 10, I know I wanted nothing more than to take a highway exit marked Gondor. I liked the feel of the word, the earthy roundness of Gon and the throaty epic of Dor. I wanted to say, “I’m from Gondor,” instead of “I’m of New Jersey,” or, at my international school, “I’m from America.” In a way I still wish I could. But the real world is made of words, too, and now I live in a word called Nuheiven that dings off the front of the tongue.