After a Feb. 22 town hall meeting about the diversity of Yale’s staff, employees and administrators continue to debate the degree to which the University promotes an inclusive workplace.

At the town hall, which was hosted by administrators including Deputy Provost for Faculty Development and Diversity Richard Bribiescas, Director of the Office for Equal Opportunity Programs Valarie Stanley and Office of LGBTQ Resources Director Maria Trumpler GRD ’92, staff members underscored unique and persistent problems with inclusion among Yale’s employees. They also noted that staff are often excluded from campuswide conversations about diversity, which often focus on faculty and students. While staff members interviewed said they were glad the University seems to be turning its eye toward inclusion among its over 9,400 staff members, they also reported inconsistent experiences with diversity on campus, with some saying Yale has made great strides in recent years and others still seeing much room for improvement.

Staff members also suggested initial steps the University could take to diversity its staff. In particular, they noted a lack of record keeping with regard to Yale’s LGBTQ staff, as well as a perceived administrative bias against staff. Elysa Bryant, an assistant administrator of human resources at the Law School, said staff members are often viewed as less important than other groups at Yale.

“In all truth, I’ve never heard anyone explore the reasons that we tend toward less diversity,” Bryant said. “The staff are left out of conversations because they are not considered equals to faculty and students.”

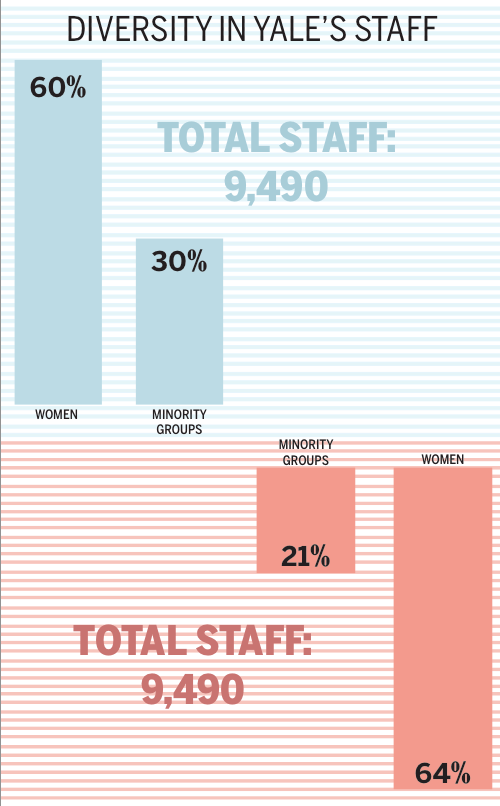

Minorities are underrepresented in Yale’s managerial staff, which includes 4,200 employees. 30 percent of Yale’s staff is from minority groups, but minorities represent only 21 percent of managerial staff, according to Vice President for Human Resources and Administration Michael Peel. Women managers, on the other hand, are overrepresented relative to the total staff population, as they represent 64 percent of managerial staff, compared to 60 percent of total staff. Peel acknowledged that these minority discrepancies were problematic.

“The greatest remaining diversity challenge we face with our staff is having more minority and female role models and mentors at the very top of our organization,” he said. “We have made great progress in recent years, but we are still not where we would like to be.”

Still, staff members and administrators disagreed on how much Yale needs to improve its staff diversity.

Trumpler said she does not see a problem with the staff’s diversity. She said she thinks campus affinity groups, like those for LGBTQ people, have already addressed the difficult questions.

Trumpler also said staff members’ experiences differ greatly depending on where they work. While some staff may have opportunities to engage in campus discussions about diversity through opportunities like administrative committees, other departments at Yale offer fewer outlets. There is no norm for staff engagement at Yale, she said, and while some schools at Yale have committees with staff, student and faculty representation, other schools do not.

But Trumpler also noted that because many staff members are private about their LGBTQ identities, and Yale lacks any method to compile diversity statistics, the University does not have accurate statistics about how diverse it really is or whether it is truly meeting its staff’s needs. Yale should collect better information about its staff in order to tackle diversity, she said.

The University has taken first steps toward promoting workplace inclusivity: the LGBTQ Staff, Faculty and Postdoc Affinity Group, run through Yale’s LGBTQ Network, has targeted LGBTQ candidates at Yale’s job fairs by offering information about what working at Yale is like for LGBTQ individuals, Trumpler said. Once hired, openly LGBTQ staff have one-on-one meetings with new employees who sign up for the affinity group.

Peel said that after a decade of diversity work, Yale’s staff is more diverse than it has ever been. Yale’s staff diversity is also better than schools both in and outside the Ivy League, he added.

One of Yale’s strategies for finding more diverse staff members, Peel said, is to hold available positions open for longer and wait to hire more diverse candidates. Yale must exhibit care and discipline when selecting the candidate pools it draws its staff from, he added. Expanding the candidate pool over the last three to five years has been especially effective in diversifying the staff, Peel said.

Different sections of Yale’s staff have dealt with increasing diversity in different ways. The medical school, for example, has made efforts to expand resources for people with disabilities. Medical School professor Carl Baum, who chairs the provostial advisory committee on disability resources, said the committee has collaborated with many different staff members, from architects and human resources to Information Technology Services and librarians, to make Yale more inclusive.

But Bryant said the intimidating public persona the University exudes, with its prestige and traditions, may discourage staff participation in conversations about inclusion. If Yale is to improve its diversity, she said, it must change the staff’s perspective by being less scary and more welcoming.

If staff feel intimidated by the University itself, there are other places where they can feel more comfortable engaging with Yale on diversity. Laurie Kennington, president of the union Local 34, pointed out that the union offers some staff members a space to negotiate and discuss issues of diversity along with the rest of the Yale community.

Staff diversity has been a priority for Local 34, which was integral in Yale’s recent commitment to hire 500 staff from New Haven’s poorest neighborhoods. Kennington said that if Yale follows through on this commitment, it could help improve the racial diversity of the staff, since those neighborhoods are predominantly black.

Still, Kennington acknowledged that Local 34 does not reflect the racial diversity of the city. Kennington said her neighborhood, Fair Haven, is predominantly Latino, while Local 34 is only around 3 percent Latino.

“We were proud to be a part of the protest that the undergraduates led, and we’ll follow their lead in this discussion,” Kennington said, referring to student activism last semester surrounding racial justice.

In fall 2014, Yale employed 1,168 service and maintenance staff.