The Obama administration proposed an executive action last week that would require companies with over 100 employees, including universities like Yale, to report to the federal government how much they pay their employees by race, gender and ethnicity.

On Jan. 29, the White House — in partnership with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Labor — proposed additions to the 2009 Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, legislation that aimed to make it easier for workers to challenge unequal pay. If Obama’s proposal takes effect in 2017, Yale would be legally required to release information it currently keeps to itself. Yale professors and equal pay advocates showed support for the action, stating that all institutions, including the University, should be more transparent about how much employees are being paid.

“It’s a step that could improve fairness for women and underrepresented groups in academic medicine,” medical school professor Barbara Burtness, who is also a member of Yale’s Committee on the Status of Women in Medicine, said. “There will undoubtedly continue to be bias in the ways in which academic work is evaluated, but I see this ruling as a very constructive step.”

Obama’s proposal rose out of an April 2014 recommendation from the National Equal Pay Task Force, and would bring to light the salary information of more than 63 million Americans. The EEOC released a report last week in conjunction with Obama’s executive action, stating that the data will help the commission better identify possible pay discrimination and help employers promote equal pay in their workplaces.

Transparency is especially important in the private sector at places like Yale, Burtness said, because many government-sector jobs already report salary data and have narrower gender pay gaps than the private sector.

Burtness also called into question historical explanations for the pay gap, which assume that women make different choices about their work-life balance or devote more time to their families than men do, leading to fewer promotions and lower salaries among women. Recent studies in academic medicine have put these assumptions in doubt, and reveal that even after adjusting for productivity, women are still less likely to be promoted than their male colleagues, Burtness said.

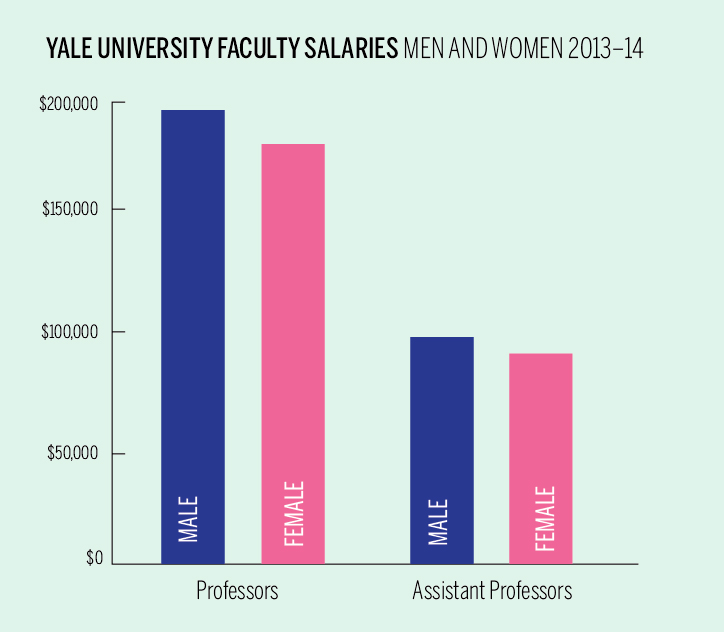

An October 2015 report released by The Chronicle of Higher Education found that male faculty at Yale earn on average $12,564 more than women. Still, the data — which was collected from 531 Yale professors — also shows that Yale’s gender pay gap is $400 smaller than the gap at the average four-year private college.

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Tamar Gendler said the FAS does not have a gender salary gap when controlling for a faculty member’s level of job experience or years since he or she received a Ph.D.

“Male and female faculty in the FAS who have the same level of job experience, who work in the same fields, earn equivalent salaries,” she said.

FAS Dean of Academic Affairs John Dovidio, who runs the FAS faculty salary process, acknowledged an “illusory difference” in pay between men and women in the FAS, but he said that difference was due to fewer women with advanced ranks and experience in the FAS, not to any institutional inequality in salary. Dovidio added that this illusory difference will disappear over time as women enter academic administration in higher numbers and as departments become more evenly distributed by gender.

But Allison Tait LAW ’11, a former postdoctoral associate in the Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Department who sat on the Women Faculty Forum while she was at Yale, said she was skeptical about the administration’s claim that women and men earn the same amount after accounting for years since their Ph.D.

“It seems unlikely that there’s perfect gender equality in the pay, even accounting for time [since one’s Ph.D.],” she said. “I’m pretty sure no institution has perfect pay equity. It seems like a pretty large claim.”

According to Tait, Yale faculty receive some information about the University’s “pay ranges,” but that data is not broken down by race, gender or even department. Gendler and Dovidio did not respond to a request for data on University salaries.

Tait said that although Yale keeps salary information very private, the FAS administration has been working diligently, using internal salary reviews, to get better pay equity among the faculty.

“Institutions would prefer minimal levels of transparency on salary,” she said. Nonetheless, she emphasized that salary transparency is “a good bargaining tool for everybody. It’s vital information to be a better negotiator.”

Similar governmental reporting programs exist outside the United States, Tait said. In Switzerland, for instance, Swiss government contractors must not only disclose their pay gaps, but they also are not permitted to have more than a certain level of pay inequality.

Public health and economics professor Jody Sindelar urged caution in analyzing any statistics that may emerge as a result of the executive action, noting that breaking down paychecks by race, gender and ethnicity could create a misleading picture of pay equity at Yale. If Obama’s action requires companies to report average salaries by race and gender — as opposed to controlling for factors like faculty rank, years since Ph.D. and department — Sindelar said, “the story will be very different.”

“There are many factors critical to understanding the data,” she said. Because some departments like Economics and Engineering have far fewer women, she added, the data could be skewed.

Women Faculty Forum Chair and School of Medicine professor Paula Kavathas said that although accountability and transparency are important, disparities by department can make reporting salaries by gender complicated.

Obama signed the executive action on the seventh anniversary of the Lilly Ledbetter Act’s enactment.