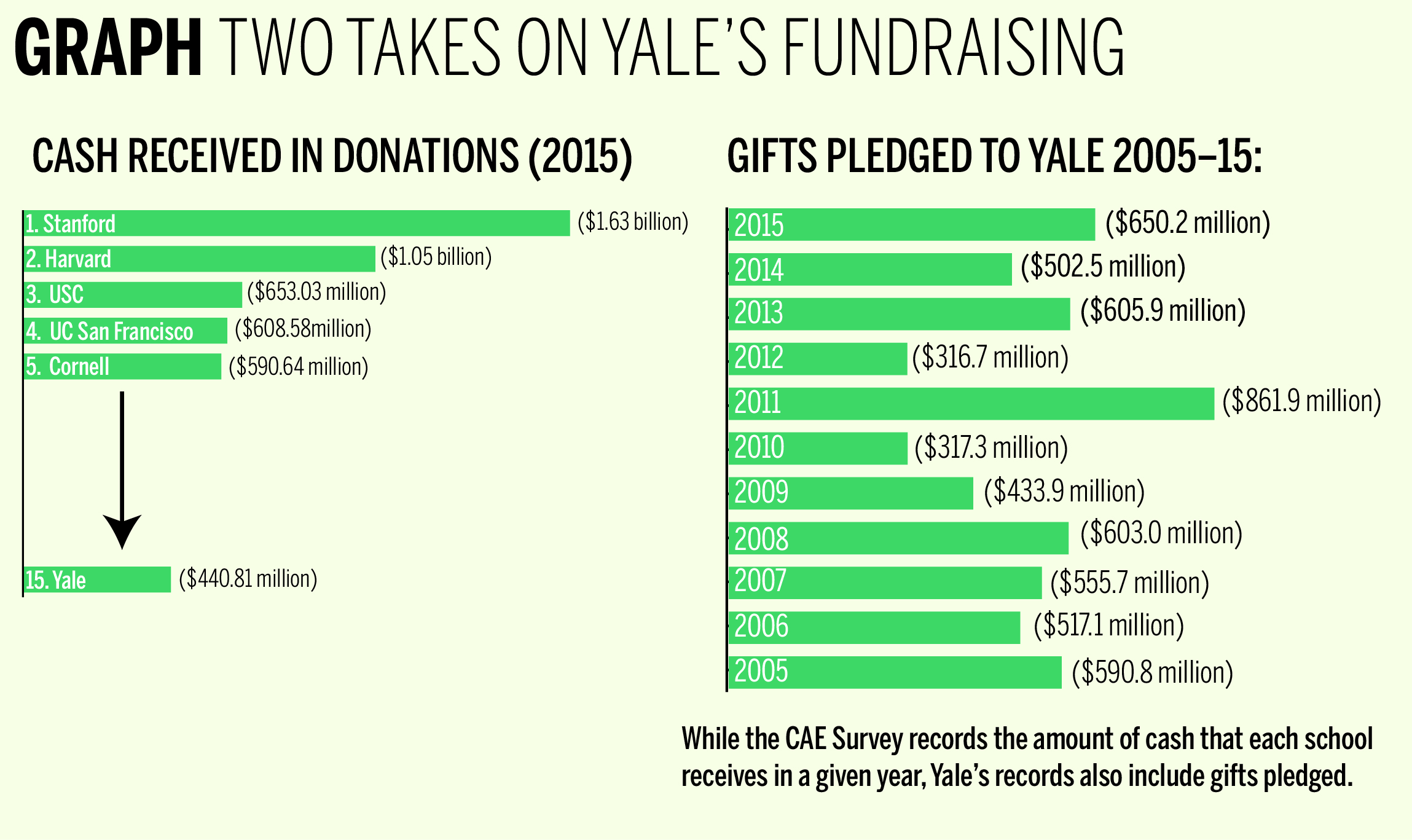

Yale ranked 15th in a list of charitable contributions made to universities nationwide last year, the same as the year before, according to a survey released last week. But top administrators say the results are not indicative of Yale’s fundraising strength, noting that the survey did not account for pledges promised for future years — which, if considered, would bring Yale’s fundraising in fiscal year 2015 to its second-highest ever.

According to an annual survey by the Council for Aid to Education, an organization that collects data on university fundraising, Yale collected $440 million in funds in fiscal year 2015, a jump of $10 million from the year prior. Still, in the past few years, Yale’s fundraising totals have fallen behind other schools like Stanford — which topped the list with a staggering $1.63 billion in 2015 — and Harvard, which came in second place with $1.05 billion. But University President Peter Salovey, who told the News that he takes the responsibility of fundraising for Yale “very seriously,” said the survey results paint an unfair portrait of the University’s current fundraising efforts. In figures Salovey sent to the News that summarize the amount of money committed to the University each year, rather than actually given, Yale’s financial picture is more optimistic.

“In the year ending June 30, 2015, Yale received more than $650 million in pledges for new gifts. This is the second-highest total in Yale’s history, exceeded only by the final year of the last [capital] campaign — and we are not in a campaign at present,” Salovey said.

Yale has fallen considerably in the CAE rankings since fiscal year 2012, when the University finished in third place nationally with around $544 million under then-University President Richard Levin. Vice President for Alumni Affairs and Development Joan O’Neill said Yale finished its last capital campaign in 2011 and that the University is currently planning its next one.

O’Neill added that the results of the CAE survey focus on current cash payments rather than taking into account the future financial well-being of the University, which includes promised donations.

“Our results this year are consistent with our level over the last few years,” she said. “CAE does not look at commitments which represent pledges and new gifts, and yet that is the figure that reflects the pipeline of future cash to come to the University.”

Salovey said donors often fulfill their pledges to Yale over five years. So in focusing on cash received, he said, the CAE’s 2015 numbers are delayed because they partly reflect old pledges.

O’Neill said the University is confident its relative standing will improve in future years. She said Yale has received $304 million in commitments as of December 2015 for this fiscal year — $79 million more than it had at this time last year. She also said recent big pledges made to the University will be paid out over several years, so they will be reflected in future CAE numbers.

The president of Yale has traditionally played a large role in fundraising for the University, and Salovey said he spends much of his time fulfilling that role.

“In general, when I am not in New Haven, I am on the road visiting with alumni, parents, friends and corporations encouraging them to provide financial support to the University,” Salovey said.

Salovey said that schools like Harvard and Stanford are able to draw on a larger alumni pool than Yale, a factor that contributes to their relative success. Yale enrolls just over 12,300 graduate and undergraduate students, compared to about 16,000 at Stanford and 21,000 at Harvard.

Yale traditionally raises a higher percentage of funds from alumni than from non-alumni, O’Neill said, noting that alumni gave 58.6 percent of total cash and 70.5 percent of total pledges last year. O’Neill added that many of Yale’s peer institutions have had success in getting donations from non-alumni, and that while Yale has made strides in this area, the University will focus more attention on soliciting non-alumni, such as the parents of students, for donations.

Yale’s relative performance also is impacted by its location, O’Neill said.

“The fact that we are not located in a major city and that we do not own our hospital makes us very different than many schools who perform especially well in this area,” O’Neill said. “But we still feel there is room for considerable growth.”

Ann Kaplan, director of the CAE’s annual survey, said there was a drop of almost $4 billion in contributions to educational institutions following the 2008 financial crisis. It took until 2013 before contributions had returned to pre-recession levels. Fiscal year 2015 was the highest year on record for gifts at $40.3 billion.

The CAE survey counts any gift or donation that must be claimed on a tax form toward a school’s annual total fundraising, she said. For example, valuable artwork and bequeathals for future construction are monitored by the CAE. According to the survey results, Stanford has topped the list every year but one in the past decade.

But drawing conclusions about a school’s spending power from the CAE data can be misleading, Kaplan said. For example, donations are often “restricted” by their donors, which means schools cannot spend the money however they please. In 2015, 7 percent of all gifts to schools were unrestricted.

Last year, Yale collected $41.1 million in unrestricted dollars, which went toward the University’s operating budget, O’Neill said.

Furthermore, Kaplan pointed out that schools are more than just academic institutions. Thus, a better metric of a school’s financial health might be to measure how much it fundraises relative to how much it spends annually, she said.

“You’re not just running an educational institution, you’re running a multipurpose nonprofit,” Kaplan said.

O’Neill said a recent analysis conducted by the University reveals that Yale’s cost per dollar raised — based on spending University-wide for alumni affairs and development — is lower than all of its peers.

The CAE survey was first conducted in 1957.