Kimberly Tighe’s ex-husband died on Jan. 7, but she still came to work like it was any other day. It was the same day she realized she might lose her job. Two weeks later, she was laid off.

Tighe had worked as a technical assistant with Yale’s Information Technology Services for 15 years. Her daughter, who worked for Yale’s Campus Technology Services, was also laid off at the same time.

ITS, which employs hundreds of Yale’s over 9,000 administrative staff, is responsible for manning the University’s IT Help Desk, managing Yale email addresses and taking care of the University’s software and hardware. But in recent weeks, according to union leadership, the University has implemented the latest in a series of administrative layoffs, drawing frustration and resentment from employees and union members.

“In order to further close our budget gap, some involuntary layoffs have taken place,” Yale Chief Information Officer Len Peters wrote in an email to ITS staff last Thursday. “Moving forward, we will continue to look for ways to be more cost-effective and agile with our services.”

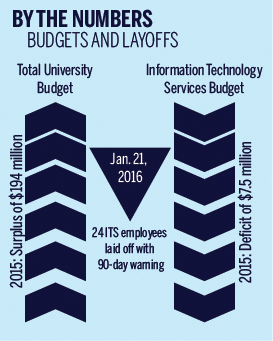

University spokesman Tom Conroy did not specify how many employees are being laid off. But Laurie Kennington, president of Local 34, one of Yale’s unions, said the number is 24.

Four years ago, ITS’s budget deficit was around $4 million. Since then it has ballooned to around $7 million, according to Tighe. But Tighe, who said her department makes a surplus each year, does not know why money is being lost.

“It just makes no sense to me, I guess. Where is this deficit?” Tighe asked. “I don’t think anyone saw it coming as fast as it came.”

The laid-off staff will receive 90 days’ full pay and benefits before they must leave, Conroy said. After that period, Conroy said, the staff will receive some compensation based on the type of work they were doing and how long they had been working at Yale. They will not, however, receive their retirement benefits. Conroy added that out of “deference to the staff who are being laid off,” their names and departments are not being identified.

For Tighe, the process began at a Jan. 7 meeting, where her bosses asked her to think of ways to restructure and streamline her department in an effort to lower costs, she said. Last Thursday, Tighe was called into another meeting. At the table sat two co-workers, her director and a representative from Human Resources. No union representatives were present. Tighe is a member of Local 34.

Realizing what was going on, Tighe said, she rose from her chair and stormed out of the room, demanding the presence of a union representative. There were none immediately available, and the meeting proceeded.

“We were completely blindsided. We felt ambushed,” Tighe said.

Now, Tighe said she does not know what she will do. If Yale does not rescind the layoffs by April 19, the end of the 90-day period, she will apply for another job at Yale.

“I just want to retire with my benefits,” Tighe said, speculating that the layoffs targeted employees with better, more expensive benefit packages.

Kennington said that of the approximately two dozen employees who were laid off, 10 were Local 34 members. Kennington said that justifying the layoffs by claiming a need to cut costs does not make sense.

“The University has announced a $196 million surplus, but ITS is claiming a $7 million deficit. It doesn’t add up,” Kennington said.

When asked to give specifics about Yale’s cost-cutting measures with regard to ITS, Conroy said ITS needs to find ways to balance its budget “as part of an overall balanced Yale budget that funds new initiatives and reflects evolving research and teaching priorities.”

Peters said in his email to ITS staff that the layoffs were part of “required cost reductions” that include reducing services, finding cheaper hardware contracts and providing “voluntary layoff incentives” to reduce the size of the staff.

According to Vice President for Human Resources and Administration Michael Peel, the University has asked administrative departments to “find 1 percent productivity each year from their budgets.” Furthermore, Peel said Yale laid off fewer people this year than it has done since before the 2008 financial crisis, although he noted that Yale should keep spending levels low to avoid finding itself in a “major budget crisis which causes painful layoffs and other urgent cost-cutting.”

Yale’s endowment dropped by 25 percent overnight after the financial crisis, Peel said. Even after the crisis, Yale’s spending had to be kept down. Only recently has Yale been able to spend more money on initiatives that grow the University, he added.

“Yale had to significantly reduce its budgets to live with the reduced amount of money coming from the endowment and other funding sources,” Peel said.

But despite the endowment’s strong returns over the past few years — Yale’s endowment saw an 11.5 percent return last year, one of the highest in the Ivy League — Peel said the endowment is not back to where it was before the crisis when adjusted for inflation. Additionally, he said, salaries, benefits, operating costs and the like have risen over the past seven years, creating a $400 million spike in the University’s total operating costs. As a result, Yale is still reducing the budget of every area of the University, from Science Park to central campus. Yale currently has around 9,490 administrative staff, and while this number has increased by about 200 positions in the past four years, this growth is slower than the growth of the University as a whole.

“Each of these actions help to lower our annual expenses,” Peters wrote in his email.

These layoffs may affect the University’s contract negotiations with its unions. Kennington said job security will be Local 34’s number-one concern during negotiations prior to the union’s contract expiration in January 2017.

Kennington called the layoffs “an unacceptable way for the biggest employer in town to save money.”

Furthermore, Kennington said, the layoffs both demoralize the staff who remain employed and create an undue burden for them as they must compensate for the work of their co-workers who have been laid off.

Although Jo-Ann Dziuba, an ITS employee of 28 years and a member of Local 34, was not laid off, she said she is fighting for those who were, through her work as a union representative.

“I am trying to help them because we want our jobs,” Dziuba said. “We know technology is changing, and we want to change with it. Don’t just cut us off.”

Anxiety persists among some of Yale’s administrative staff members, as worries over job security create an atmosphere of fear and suspicion. Of 22 administrative staff members in ITS contacted for this article, all but Tighe declined to speak on the record because they said they feared losing their jobs.

“I’m not comfortable doing an interview. Anything is possible,” said one employee in Information Technology Services. “I don’t want to get caught up in something.”

While some administrative staff are members of Locals 34 and 35, which collectively represent nearly 5,000 blue-, pink- and white-collar Yale employees, staff without the protection of a union said they do not have the same degree of job security as union members.

An administrative employee, who asked to remain anonymous because she feared retribution, said the culture among the administrative staff has changed during her time here.

“Ten years ago, people talked about ‘the University.’ Now people talk about ‘the Corporation,’” the employee said. “People understand that we have to be cost-conscious, but there’s a feeling that everything is being done for the dollar instead of being done for the good.”