Yale graduate students seeking unionization may look with interest and expectation at two cases currently before the National Labor Relations Board whose rulings could upend decades of labor law precedent surrounding graduate student employment.

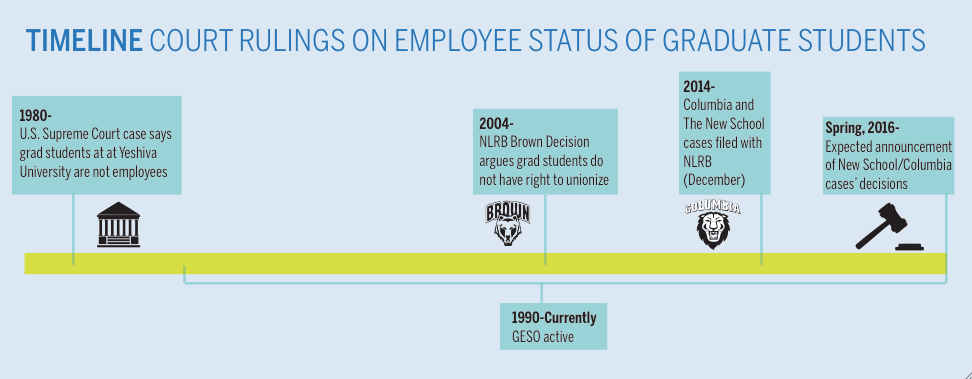

On Dec. 16, the American Council on Education — a higher-education organization with around 1,700 members, including Yale — weighed in on a pending NLRB court case between The New School, a university in New York City, and its student employees. In a friend-of-the-court brief — a document filed by an interested party that is not actually involved in the suit — the council argued that graduate students should not be treated as employees, but rather as students. The New School case, along with a similar case at Columbia University, could determine the fate of Yale’s Graduate Employees and Students Organization, a group of graduate students formed in 1990 that has held four demonstrations in the past 18 months while attempting to form a union and obtain bargaining power in its negotiations with the University. The New School and Columbia cases were filed with the NLRB in December 2014, and the NLRB is expected to make a decision by mid-March or early April of this year.

The New School case has the potential to overturn a 2004 NLRB decision at Brown University in which the board decided that Brown’s graduate students did not meet the NLRB’s definition of employee in the National Labor Relations Act and thus could not unionize. If the Brown decision were overturned, Yale — which has historically opposed graduate student unionization — and other private universities would be affected by the ruling, said Jonathan Clune ’74 LAW ’79, senior associate general counsel at Yale’s Office of General Counsel.

“The faculty supervising the [teaching assistants] in courses … would become the supervisors of those students. So the NLRB would look at that [relationship] as a supervisor-employee relationship,” Clune said. “For labor-law purposes, graduate students who are working [would] be treated as employees for those purposes, for that aspect of their work.”

The ACE’s brief argues that the Brown case was correctly decided and that graduate students’ relationship with a university is fundamentally one of “student-teacher,” not “master-servant.” The brief further states that teaching and research assignments cannot be used for collective-bargaining purposes without infringing upon the “predominantly academic character” of the graduate student-university relationship.

“Such a reversal will adversely impact fundamental, core aspects of the manner in which higher-education institutions across the country structure and deliver graduate education,” the brief continues. “It will intrude unnecessarily upon academic freedom and the relationship among our nation’s universities, professors and their graduate students.”

Yale’s administration worries that such changes could hurt Yale academically. Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Tamar Gendler said Yale shares the same concerns voiced in the ACE brief. Gendler was adamant that the teacher-student relationship is of central importance to Yale’s academic mission, and voiced concern over the future of graduate student-faculty interactions at Yale in the event of a pro-union NLRB ruling.

“I am concerned that this relationship would become less productive and rewarding under a formal collective-bargaining regime in which professors would be ‘supervisors’ and their graduate students ‘employees,’” Gendler said, adding that Yale administrators welcome “a full, robust debate about graduate-student unionization on the Yale campus.”

The NLRB could decide any number of ways, and lawyers involved with the case said there is no way of anticipating the board’s eventual ruling. The NLRB, whose five governing members are appointed by the president of the United States, has been known to swing pro-union during Democratic presidencies and align with corporations during Republican ones. The Brown case was decided after George W. Bush ’68 appointed right-leaning members to the NLRB, but the New School and Columbia cases come after Barack Obama has appointed several members more sympathetic to unions. Vice President and General Counsel of the ACE Peter McDonough said the court may either write decisions for both the Columbia and New School cases, or write a substantive decision in one case and simply refer to it in resolving the other one.

Furthermore, McDonough said, the NLRB must contend with a 1980 U.S. Supreme Court decision involving graduate students at Yeshiva University. The Supreme Court said that corporate and business workplace environments differ fundamentally from the academic world, in which the distinctions between graduate students’ responsibilities are less clearly defined.

“In the NLRB’s decision in Brown, the board said that the relationship between the graduate students’ assisting [through teaching], and pursuing a Ph.D., are inextricably linked,” McDonough said.

While labor laws may define employment one way, other definitions, like those for tax purposes, view employment in a different light, Clune said. As a result, graduate students do not always fit smoothly into a single definition of employment.

GESO Chair Aaron Greenberg GRD ’18 did not directly answer questions about the New School case, but said that over 70,000 graduate teachers and researchers are already in unions at public universities and that GESO is part of a push to bring unions to private universities like Yale.

There are approximately 3,000 graduate students at both Yale and at Columbia.