My room felt smaller with Kevin in it.

We were watching Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and I couldn’t focus because Kevin’s nearness scrambled my senses. First the walls began encroaching on me. Then everything dissolved into fragments. The cold edge of my desk jutting into my knees. Tinny soundtrack emerging from my laptop speakers. Kevin beside me, not touching but close enough that I could feel the heat emanating from his arm.

It was December 2014. I’d known Kevin for six years and he’d been flirting with me for a month and a half. He had sleepy eyes and feathery hair and our conversations were as bland and sticky as sugar water. I did not believe at first that he had been flirting, despite all the obvious signs: the smiles in the hallway, the way he seemed to show up at the library every time I was tutoring. I was not that sort of girl, the sort who knew what it was like to be wanted.

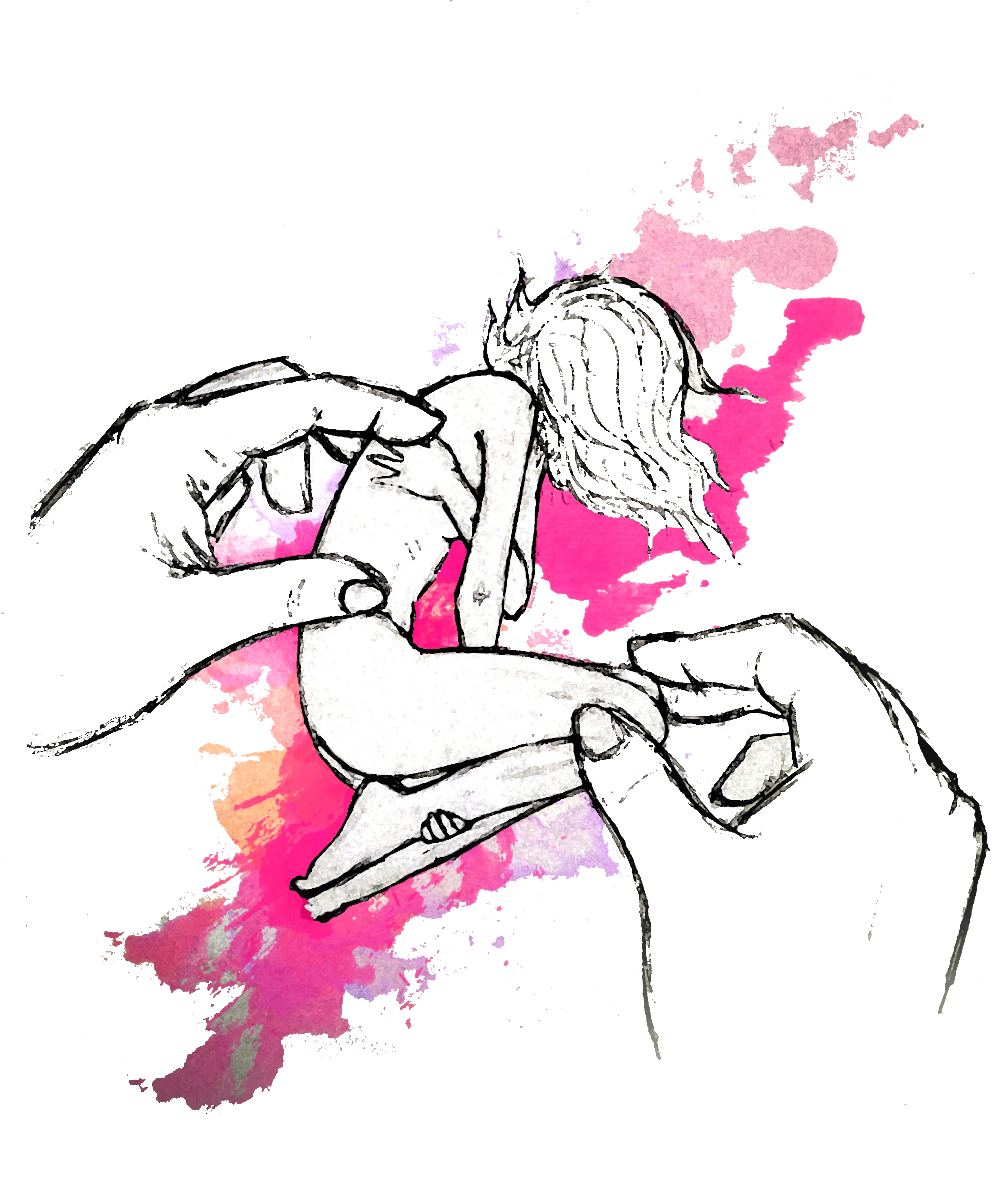

Yet here he was, at my desk, his glasses fogging up a little. Here we were. I could see his hands twitching — he was thinking, I imagined, about reaching out for mine. I wondered what his hands would feel like: whether they would be soft or callused, whether they would be bigger than my hands and by how much. I felt inescapably aware of him next to me, of his arm ghosting mine, his breath rattling in and out of his mouth. I felt inescapably aware of my own body.

I tucked my feet onto the chair, and suddenly — for the first time — I wanted to be small. My legs seemed too long, too incompressible, my shoulders too thick. I wondered if I took up too much space.

—

I know I am not the first girl to have felt the desire to shrink. By shrink, I mean in every sense of the word — not just physically or mentally, but expressively, socially. “I asked five questions in genetics class today and all of them began with the word, ‘sorry,’” proclaims Lily Myers in her slam poem “Shrinking Women,” which has almost 5 million views on YouTube.

Start looking and the phenomenon pops up everywhere you turn. Diet pills. Photoshop. Corsets. Bound feet. The current fad seems to be sadness: the glorification of sad girls, girls who emotionally pull themselves out of the camera frame. Girls who cry, prettily. (“I’ll wait for you, babe / Don’t come through, babe, you never do / Because I’m pretty when I cry,” croons Lana Del Rey in her 2014 album.) How much critical acclaim did Jeffrey Eugenides garner for The Virgin Suicides, again? Sad girls represent the mythologized, enigmatic feminine essence — but only if they don’t share their suffering. Only if their sadness is internalized. Only if their sadness is an act of retraction.

For weeks after I watched the movie with Kevin, I kept revisiting that moment of wanting to be consumed, of wanting to be containable. Walking home from school, I watched my shadow stretching ahead of me and felt oddly pleased when the sun struck me at an angle that made it appear paper-thin. I wanted to be something that could be taken in. That could fit entirely in the seat of my chair. I wanted to be subsumed, and it disturbed me that I could want such a thing, that I could want my presence to be an absence.

In her essay “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” novelist and essayist Leslie Jamison describes a memoir about anorexia written by Caroline Knapp, who undresses before her mother in the hopes that exposing her thin bones will be a sufficient cry for help. But her mother doesn’t notice. “I feel like I’ve heard it before,” Jamison writes. “The author is still nostalgic for the belief that starving could render angst articulate.”

Artist Audrey Wollen, who developed “sad girl theory” in 2014, posits that this historical “starving” by women — manifested in hunger strikes — is in fact a method of female empowerment. In Wollen’s view, shrinkage can be vocal, and retraction can speak for us. We want people to care whether we’ve lost weight, to comment on the fact that we don’t spend so much time with them anymore, to ask why we seem upset, to say “Are you okay?” If we shrink, people reach out to us. They fill in the places we make for them.

—

Soon after Kevin and I watched the movie, he asked me out via a Facebook message. The day after, I went to the Museum of Modern Art. I wandered alone through an exhibit of Robert Gober’s works from the 1980s: a sculpture of cheese with hair, long wax legs in a fireplace, black wallpaper covered with drawings of genitalia. Gober made me feel surreal, out of body. I had postponed my answer to Kevin.

One friend told me I was being ridiculous and that dating Kevin didn’t mean anything serious. Another told me to do what felt right for me. Another told me Kevin was a creep. I couldn’t stop remembering his hand twitching as we watched Joel chase after Clementine in the corridors of memory. Where did desire stop and flattery begin? One friend said, “If you like him, then date him. If you don’t, then don’t,” like it was that simple, like I could so easily separate what I wanted from what I thought I wanted.

Kevin never forced me to agree to anything, never suggested I needed to empty myself for him. But if he had taken my hand that afternoon, perhaps I would have said yes. If he had put his arm around my shoulder, perhaps I would have leaned into him. If he hadn’t given me the chance to reclaim my space, perhaps I wouldn’t have tried to reclaim it. I wondered how I could give myself over so easily. I wondered why I felt he deserved my spaces more than I deserved them. I wondered — and then I turned him down.

I don’t mean to suggest that I am any sort of model of feminine empowerment. After all, I am certainly not the first girl to say no to a guy. But I did arrive at an understanding. An understanding of the ways in which we — as girls, as women — permit others to mold us and then pour themselves into the newly made hollowed-out space. An understanding of why we grant anyone the permission to encroach on us at all. An understanding of why we expect our shrinkage to be an act of empowerment, when it is anything but — when it does nothing but push us into smaller and smaller containers, when it does nothing to speak for us but does everything to erase what we have to say.

Why is shrinkage still the way we expect to be heard? Why do we apologize before we ask our questions? Why are we polite to people who harass us? Why do we elevate boys and call them “men” yet diminish women and call them “girls”?

That December afternoon I wanted to be small enough that Kevin could — would — put his arm around my shoulder. I wanted to fit into his negative space. Shrinkage in that moment had become my habit: no natural defect but impressed, absorbed, ingrained. But it shouldn’t be. Must not be.

Perhaps what I mean by all this is that we must learn to occupy our own spaces. My body was not in Kevin’s space that day we watched Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. That space was mine.