Commuters along the East Coast have long complained of Amtrak’s poor service and spotty on-time record. Two months after the Federal Railroad Administration released a slate of potential new plans to revolutionize Amtrak’s service in the Northeast Corridor, Connecticut residents continue to question the plans’ potential for impact, while stressing the need for updated mass-transit options in the Nutmeg State.

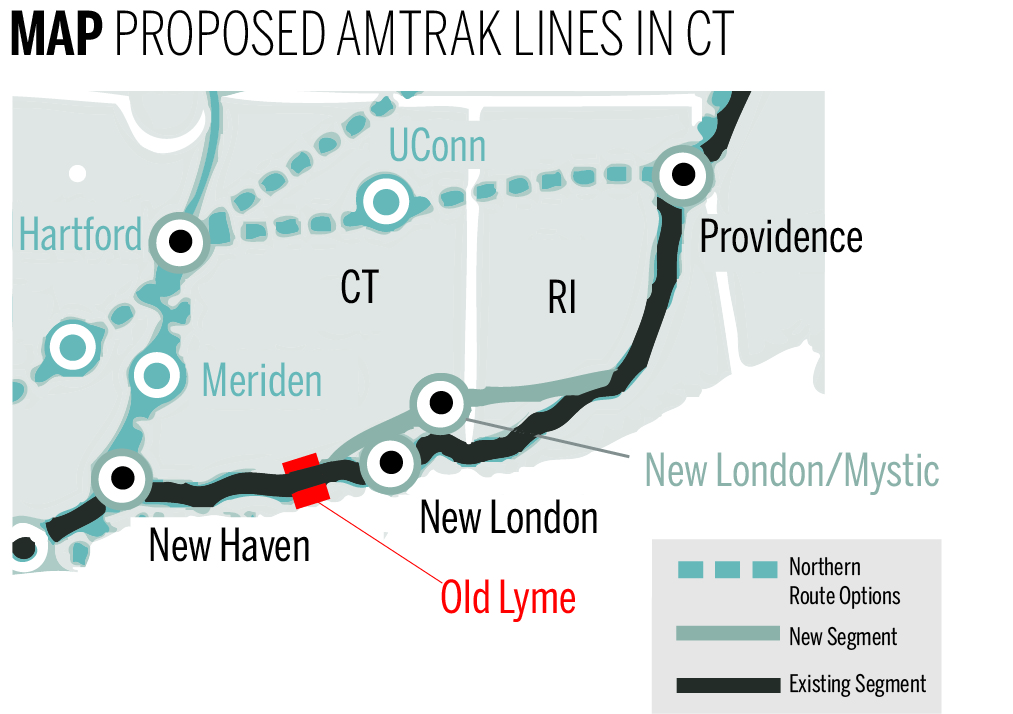

In November, the Federal Railroad Administration presented four possible visions for the future of rail travel in the Northeast Corridor. The most far-reaching option would involve transforming rail lines in the Northeast. In addition to adding new stations in Philadelphia and Baltimore, the plan would open the door to a line running under the Long Island Sound on its way from New York to Hartford, or dozens of miles of tunneling in a route north of New York City running from Danbury to Storrs, Connecticut. Another plan involves a new route in eastern Connecticut and three new tunnels, one in Baltimore and two under the Hudson River.

Connecticut residents from across the state aired their opinions at a public hearing held in Hartford last Wednesday with representatives from the Federal Railroad Administration. Many attendees expressed concern that a proposed section of new track running from Old Saybrook, Connecticut to Kenyon, Rhode Island might have a negative impact on the environment and the region’s historic town centers. Other attendees, however, were enthusiastic about the proposals that might establish a high-speed rail line running from Boston to Washington, D.C. They said access to mass transit is important for millennials across the state.

“Our companies are leaving Connecticut for Boston,” Old Lyme resident Daniel Warren said at the Hartford hearing, referring to General Electric’s recent announcement that it will leave its Fairfield headquarters. “It’s not just because of taxes — it’s because [Boston] is a town where people want to live. A strong rail connection, I think, is the future for our area … we need to make a bold, strong statement.”

Donna Farvard, an organizer for the Storrs chapter of the student-directed advocacy group ConnPIRG, agreed. She said offering alternative transportation options to cars — including trains and bikes — would make young professionals want to stay in the Northeast instead of moving to more transit-friendly cities elsewhere in the country.

But some residents are more concerned about the possibility that a new rail line proposed in one of the four plans might disrupt eastern Connecticut. Bonnie Reemsnyder, the first selectwoman in Old Lyme, said a new line might unalterably change the fabric of her town.

“This plan would decimate the heart of our community,” Reemsnyder said. “We are a small town with little central community area, and what we do have is extremely important to our history, economy, character and sense of community. This plan would impact our only commercial area.”

Toni Gold, a Hartford resident, said railroad routes should be chosen with particular care and that none should go through the center of towns and cities. A poorly placed route, she said, might destroy the “small-scale pastoral, rural towns” that comprise much of the state.

Multiple attendees spoke on the importance of “multimodal” transportation that allows commuters to combine two forms of transportation into one trip, allowing commuters increased flexibility. Bruce Donald, chair of the Connecticut Greenways Council, said Amtrak should work to provide bicycle racks on trains.

Steve Mitchell — a board member from the East Coast Greenway Alliance, a body that oversees the administration and construction of a proposed Maine-to-Florida bike path — also spoke at the hearing. Mitchell said allowing bicycles on trains might help Connecticut attract young professionals, as millennials favor to bicycle-friendly cities like Boston.

Joseph McGee, vice president of public policy and programs for the Business Council of Fairfield County, was skeptical of both ideas, which involve substantial amounts of potentially costly tunneling in Connecticut. He told the News that devoting those funds to improving the current four-track line running between New Haven and New York might be more efficient.

“We think it’d be much cheaper, and it’s reinforcing the historic commitment to these growth corridors that have existed for 150 years linking New Haven and New York,” McGee said. “You’re proposing enormous environmental challenges, when for far less money and far less disruption, you may be able to accomplish similar things with existing rail lines.”

McGee also cast doubt on the wisdom of pursuing high-speed intercity travel rather than what he described as a more urgently needed high-speed commuter rail system connecting New York to New Haven and other towns in Connecticut. The prospect of reaching Boston in 90 minutes from New Haven sounds exciting, he said, but a 60-minute travel time between New Haven and New York offers greater opportunities for economic growth.

Attempts at transportation reform have occurred at the state level, too. Gov. Dannel Malloy is currently pushing for a $100 billion “transportation lockbox” to be enshrined in the state constitution, though the proposal failed to pass in the General Assembly’s December special

Correction, Wednesday, Jan. 20: The NEC Future plans were in fact released by the Federal Railroad Administration, not Amtrak. The FRA and Amtrak are separate organizations.