Since arriving at Yale in 1985, Chief Investment Officer David Swensen GRD ’80 has raised the University’s endowment from $1.3 billion to its largest size ever, $25.6 billion. But this success is difficult to imitate.

Economists and financial commentators are fond of using Swensen’s successful investment strategies as a model for private investment, recommending that individuals imitate Yale to grow their own wealth. A Nov. 20 article titled “Three Lessons from Yale’s Endowment Fund” by John Rekenthaler, vice president of research at the investment management firm Morningstar, is the latest in a sequence of articles translating Yale’s strategies to the general public. But Swensen has argued repeatedly in articles and books that imitating Yale’s methods may not yield the best results for private investors who have less money and less time to wait for returns than Yale does. Even as the public continues looking to Yale for the secret to financial success, some analysts recommend that investors look elsewhere for guidance and take investment into their own hands, rather than relying on external models.

“Nothing succeeds like success,” said William Jarvis ’77, managing director of the Commonfund Institute, an institutional investment firm. “People look at Yale and want to have some of that for themselves. But the issue is that many people don’t understand how challenging it can be to manage the risks.”

In 2000, Swensen published “Pioneering Portfolio Management,” a book about how large institutions should invest their money. Across the country, thousands of institutions, including hundreds of colleges, began adopting similar versions of the methods outlined in Swensen’s book. But few saw the same success Yale did, according to a 2012 Forbes article titled “The Curse of the Yale Model.”

Five years later, Swensen wrote a second book aimed at individual investors rather than institutions. In the book, called “Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment,” Swensen casts the individual investor in stark contrast to Yale. Whereas Yale has access to a network of intelligent and connected investment managers, the individual investor has much less expertise to guide investment, he wrote. Institutions like Yale also have long “event horizons,” meaning they can invest with the view of making money over hundreds of years, an ability that individual investors lack.

The managers of Yale’s resources have an obligation to make some of those resources available to the current generation of scholars and students while preserving resources for future generations, said University Chief Financial Officer and Vice President for Finance Stephen Murphy ’87. Delaying maintenance on campus buildings or accelerating spending from the endowment might give Yale more short-term money to spend, but Murphy said such practices could lead to long-term negative consequences for future generations of students.

However, managing money is a different ballgame for a private investor. As Jarvis pointed out, a private investor might, in an emergency, need cash quickly. Part of Yale’s method is investing in “illiquid” stocks that cannot be quickly turned into cash, a practice that is more difficult for a private investor. Since Yale only needs around 5 percent of its endowment in cash each year for its operating budget, it can afford to have fewer liquid investments than the average investor.

“As Swensen correctly writes, Yale’s situation differs substantially from that of his readers,” Rekenthaler wrote in his Nov. 20 piece.

But Rekenthaler acknowledged that some concepts in the “Yale Model” do indeed translate to private investors — an idea that Swensen has also noted in his own writings. According to Swensen, having a diverse portfolio is advantageous to both Yale and to the investor, as is investment in equity, which is stock in a firm or a company. Neither investors nor institutions should try to predict when the market will fluctuate, as Swensen has said this can be futile and can lead to poor investment choices.

Still, some economists are adamant that mimicking Yale is misguided. Jarvis said any institution or individual lacking Yale’s resources should not emulate the Yale model. School of Management professor Roger Ibbotson said that if individuals tried to imitate the Yale model they would bear unnecessary costs and fees associated with investing in the kinds of asset classes in which Yale invests.

“It’s greed and overconfidence,” Ibbotson said. “People think they know more than they do. These individuals are not connected to the markets enough to recognize good deals from bad deals.”

Ibbotson went on to say that Swensen wrote his second book in part to warn private investors against copying Yale’s methods and recommend better investment strategies for the individual investor. Private investors are more likely to be caught up in investment schemes that are ill advised, Ibbotson added.

In a 2011 New York Times op-ed, Swensen wrote that investors naively trust their stockbrokers and financial advisers. He cited sites like Morningstar — which, in addition to managing investments, also provides a service that measures and rates the investment performance of stocks — as a poor way for private investors to predict the success of certain markets.

“Individual investors should take control of their financial destinies,” Swensen wrote. “The rating system merely identifies funds that performed well in the past; it provides no help in finding future winners.”

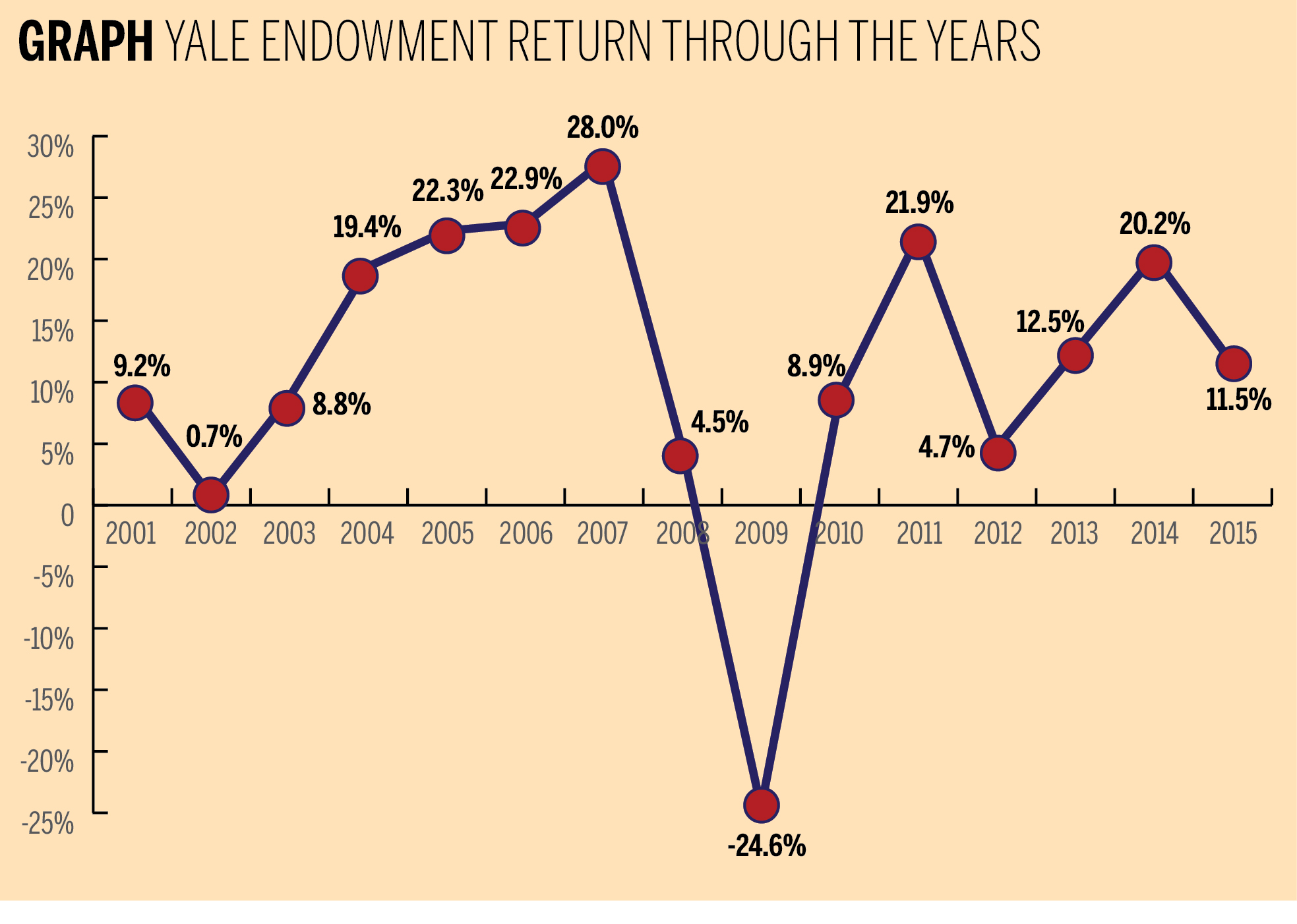

The average return on Yale’s endowment over the past 20 years is 13.7 percent.