I missed my Freshman Assembly. I spent the first Saturday morning of my time at Yale in a small chapel instead, praying; rather than the splendor of Woolsey Hall, I opted for a small bright room where I sang in Hebrew. While my freshman peers donned dresses and blazers to hear President Salovey speak, I wrapped myself in a prayer shawl and listened to the words of the Torah chanted aloud.

As a traditionally observant Jew, I observe Shabbat, the sabbath, from dusk on Friday to nightfall on Saturday each week. My Freshman Assembly conflicted with Shabbat morning prayers. Shabbat for many Jews is a time of rest and reflection, but for Jews like me who consider themselves bound to halakha, the formal system of Jewish law, Shabbat also means a specific set of restrictions. On Shabbat, I don’t write, cook, travel or use any electricity, which includes putting away my phone and computer. The category of work I don’t do on Shabbat is called melakha.

“Melakha, as I understand it, is the prohibition on engaging in creative labor,” explains Chana Zuckier LAW ’17, a first-year law student and co-director of the Orthodox Union’s Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus.

“The word is often translated [as] ‘work,’ but I think that’s inaccurate,” Zuckier says. “I think halakhically, melakha refers to things that either utilize or symbolize human creativity, and I think the idea is that six days a week we’re expected to maximize our human creativity to the best of our ability, to improve the world, and one day a week there’s a day that we stop and recognize that ultimately our ability to be creative is derived from God.”

Today, it is largely uncomplicated to observe Shabbat at Yale. My suitemates are accommodating of my practice of not flipping light switches and my unresponsiveness to texts on Friday nights and Saturdays. And because swiping an electronic key card falls into the category of forbidden labor, Yale provides me, like they do for any interested student, a manual key that opens one of the gates in their residential college, or, for freshmen, a manual key to Old Campus. To receive the key, all I had to do was fill out a form. Marc Fanelli, who works at the Yale University Lock Shop, estimates that there are 23 students this year who were given Shabbat keys.

The ease with which I acquired this key, however, is not something I take for granted.

During the 1994–95 school year, Yale announced a plan to put electric locks on all campus buildings. The plan was formed in response to a wave of crime in the area, in an attempt to reassure parents that it was safe to send their children to school in New Haven. It caused a bit of a panic — Yale was among the first universities to introduce electronic lock systems, and there was no model for how to accommodate observant Jewish students.

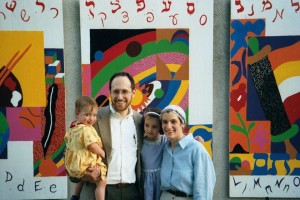

At the time, my dad, Eric Halpern ’95, was a senior and president of Yale’s Undergraduate Orthodox Community.

He remembers, “We went to lots of meetings with administrators and did not get far at all. We tried to make the case … that we needed to have physical keys, and the administration was pretty adamant that it would compromise security and so they were not really open to the idea.”

My dad describes meetings in which Yale administrators attempted to convince Rabbi Michael Whitman, who served as the spiritual advisor to Yale’s Orthodox community at the time, to change his opinion on Jewish law.

As the meetings dragged on, he says, the conversation reached a low point “when we pointed out that if the University did not make some form of accommodation, the university would be really unattractive to Orthodox Jewish prospective students.”

One administrator in particular, he remembers, accused them of blackmailing Yale by “saying if we didn’t get our way we would badmouth the University to Orthodox Jewish high schoolers.”

“At that point,” he says, “when it was interpreted as a threat rather than a concern, it really seemed there wasn’t any way to make progress on it, and that was the point at which students started expressing their concerns to their masters.”

My dad and another student were then invited to present their argument to the Council of Masters. He recalls mentioning in the course of the meeting that one student had joked that her only recourse was to knock on her master’s door to be let into her college. “One of the masters stood up and said how proud he would be to give students keys to his house and have students walk through his living room if that’s what it took,” he remembers.

After the masters took an interest in the issue, they worked with the administration to quickly resolve it. When key cards were introduced, Shabbat-observant students were provided with manual keys.

Today, not only does Yale accommodate students who observe Shabbat, but many traditionally observant students also choose to come to Yale specifically because of the quality of the Shabbat-observant community here.

Isabel Singer ’16, a senior in Morse who observes Shabbat, says that before she decided to apply early action to Yale, she visited to make sure it would be a Shabbat-friendly environment.

Singer explains that there were three reasons she came to Yale: “really awesome academics, really good music community and great Jewish community that was really strong, had a lot of observant people in it, but wasn’t exclusively Orthodox.”

Like me, Singer identifies as a halakhic egalitarian Jew: bound to traditional Jewish law but viewing women as equal citizens in religious citizenship and obligation, especially in prayer contexts. When I was exploring my college options, it was a priority for me to find a Jewish community where all students who observed Shabbat were part of a unified community, not divided based on who prayed in which settings.

Shabbat at Yale is sometimes similar to Yalies’ Shabbat practices at home, sometimes not. Evan Risch ’18, a sophomore in Trumbull, observed Shabbat before coming to Yale but cites a different “energy” in the community at Yale. “My community at home is small … the Shabbat experience there is very laid-back, not very energetic, so I was looking for that sort of energy component,” he says. “[At Yale] people are very into Jewish things like singing and davening [prayer] in addition to the social aspect.”

For Nate Swetlitz ’17, a junior in Silliman, Yale provided the opportunity to shift his Shabbat practice in a more traditional direction. Swetlitz did not grow up in a community that observed Shabbat according to Jewish law. For example, his family would drive cars on Shabbat. “When I came to Yale I definitely wanted more of a community,” he says. “I realized that since I was able to walk around everywhere and that sort of thing — that sort of changed my observance levels and now when I go home I also don’t drive.”

The community Swetlitz was seeking thrives at Yale. Risch, who is a co-coordinator of Orthodox prayer services at the Slifka Center, says that he was seeking “something active, in which I could have an active role, which usually meant a smaller community — that’s why Yale is a good fit.”

Yale is not unique in having a strong Shabbat-centered community of observant Jews. Shabbat at Princeton and Harvard, both of which have observant Jewish communities similar in size to Yale, closely resembles Shabbat at Yale: the community eats meals together, and spends time singing, playing board games, going on walks and spending unstructured time together unmediated by technology. At Penn and Columbia, both of which have a large religiously observant population, students often host smaller meals in their dorm rooms or off-campus apartments.

Penn, Princeton and Harvard all provide their students with manual keys for use on Shabbat. At Columbia, where students must sign in when entering dorm buildings that are not theirs, simply telling the guard that one is Sabbath-observant circumvents this requirement.

Dartmouth, however, has a worse reputation among Shabbat-observant Jews.

“There were certain schools that I really was not thinking about seriously because I had seen that they really weren’t Shabbat-friendly environments,” Singer says, citing Dartmouth in particular.

Dartmouth was initially unresponsive last year to my friend Cameron Isen’s request for a manual key for his freshman dorm building. Cam, who I met on a teen Israel program, began observing Shabbat shortly before he arrived at college. When asked how accommodating Dartmouth has been to his Shabbat-related needs, Isen chuckles and says, “I laugh because it’s kind of hilarious.”

When he requested a key, he says, “Initially I got a really offensive response from the school, where the Office of Pluralism and Leadership — whose job it is to advocate for minority students on campus — told me I had three options: get an exemption from my rabbi, which I took to mean ask him to change halakha [Jewish law], wait outside for somebody to let me in, or move off campus.”

Dartmouth’s Office of Pluralism and Leadership did not respond to request for comment.

Similar to my dad’s solution to resistance from leadership at Yale in 1994, Cam eventually decided to contact his dean of Residential Housing. The issue was resolved over his winter break that same year, and he now has a manual key to use on Shabbat and on holidays with similar restrictions. Cam is currently embroiled in another conflict with Dartmouth’s administration, though, over their refusal to provide students with dining options that adhere strictly to kosher standards.

I feel fortunate to be at Yale at a time when, unlike my dad or Cam at Dartmouth, I can be a fully religious person and also a Yale student.

Observant Jewish Yalies have a tradition of singing the football fight song immediately following the “Grace After Meals” on Shabbat. The tunes are very similar, and sitting in the kosher dining hall, we sing praises to God and then move seamlessly into “Bulldog.”

This is Shabbat on campus: song and tradition, for God and for Yale.