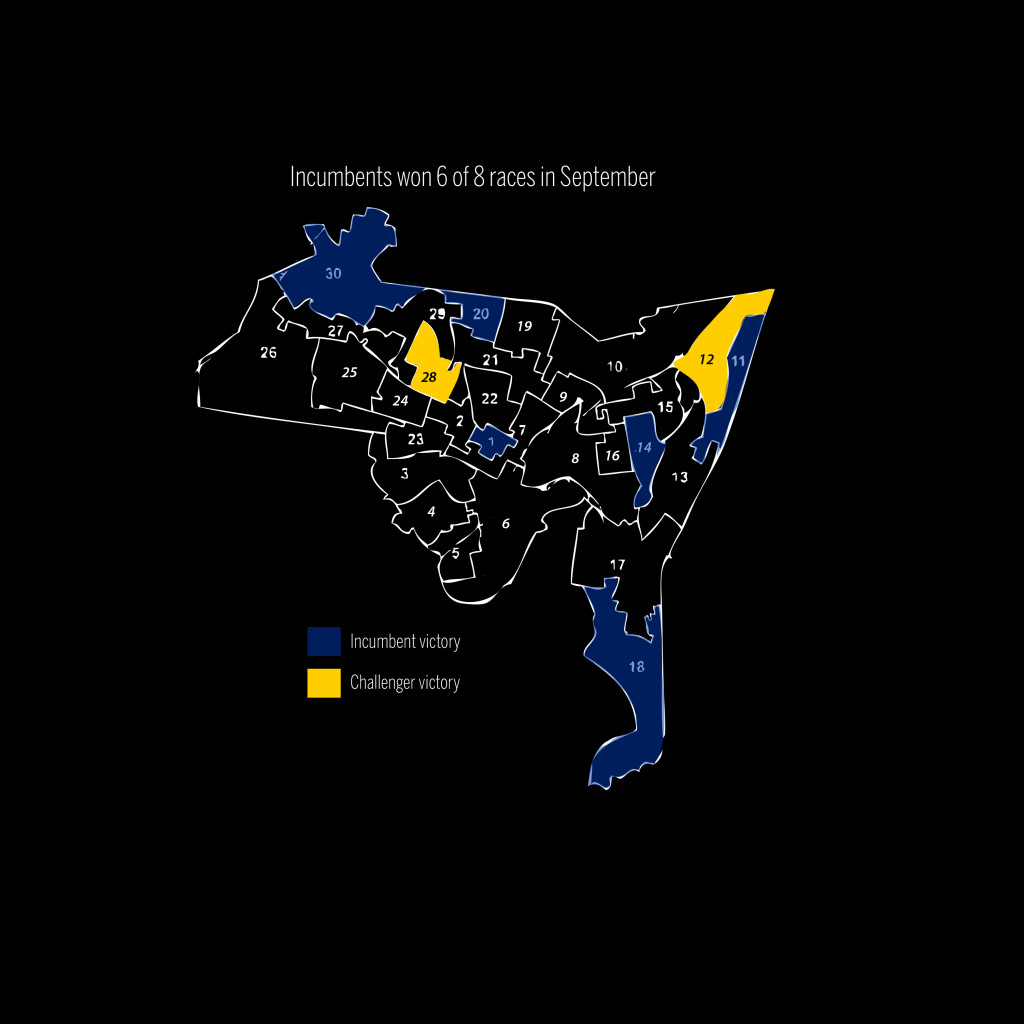

In a ritual of late-summer politics, residents of eight New Haven wards went to the polls in mid-September to vote for the Democratic candidates for alder. Eight incumbents ran; six incumbents won.

The results of the election mean that in its new term, set to begin in January, the Board of Alders will likely look much the same as it has for the past two years. This is hardly abnormal. Looking back through the records of past alders who have sat on the board, one sees many of the same names persisting throughout its history.

Those long-serving alders are often the beneficiaries of the incumbency effect, the political phenomenon wherein incumbents possess certain advantages over challengers. In New Haven, though, the traditional models don’t always hold. New Haven politics operates under a unique blend of labor unions and a Democratic machine, a model that few other American cities still espouse. As a result, local incumbents find themselves specially vulnerable nearly as often as they find themselves specially advantaged.

EXPERIENCE, FOR BETTER OR FOR WORSE

Just after 8 p.m. on Sept. 16, Fish Stark’s ’17 campaign team sat assembled in a private room in Wall Street Pizza. The polls in the Democratic primary for Ward 1 alder had closed minutes earlier, and soon the moderator would read the tallies from the voting machine. Some 10 minutes later, the results arrived via text message: Sarah Eidelson ’12 had won with 310 votes to Stark’s 175, a margin of nearly two to one. The incumbent had prevailed yet again.

That incumbency confers a significant advantage upon a candidate running for re-election is a general maxim of political science. Studies of congressional and presidential elections consistently demonstrate an advantage for incumbents, said David Cameron, a professor of political science.

Among the benefits of incumbency are name recognition, previous victories in the district, better funding, and an already-established familiarity with running a campaign, Cameron said.

Incumbency also plays two crucial roles in procuring endorsements, a hugely important factor in New Haven elections. For one, Mayor Toni Harp maintained a blanket policy of endorsing all Democratic incumbents in contested races this year. And having already served in the elected position means the incumbent has established relationships with members of the city — relationships that can be leveraged once it comes to receiving endorsements.

Both factors played a role in the Ward 1 Democratic primary. As the incumbent, Eidelson received the endorsements of a host of local dignitaries: Harp, state Sen. Martin Looney and a majority of the Board of Alders, among others. Stark, meanwhile, boasted a much smaller slate: only six alders, nearly all affiliated with the now-defunct anti-union “People’s Caucus.” Despite some prominent figures coming out in his favor — including state Sen. Gary Winfield and former mayoral candidate Justin Elicker FES ’10 SOM ’10 — Stark proved unable to match Eidelson’s backing.

And Eidelson’s campaign ensured that voters heard about her endorsements. As Eidelson stood outside the polls at the New Haven Free Public Library talking to voters on election day, she was joined by many of the alders who had backed her. Alders Jeanette Morrison, Frank Douglass and Dolores Colón ’91, as well as board president Tyisha Walker, joined Eidelson throughout the day.

These endorsements proved influential for voters. After voting, Frederick Van Duyne ’19 told the News that Eidelson’s public support from 19 of the 30 alders pushed him to cast his ballot for her.

“As an incumbent, she has a rapport with Yale and with New Haven, and with the dialogue between the two communities,” Van Duyne said. He added that Eidelson’s continued presence in the city over three years after graduating demonstrates her commitment to New Haven.

Sweyn Venderbush ’18 echoed that sentiment. He said he voted for Eidelson based on her “proven track record in the city.”

Van Duyne’s remark reflects a political reality in Ward 1 that rarely applies in the rest of the city. Outside Ward 1, a candidate’s commitment to staying in the city is rarely, if ever, challenged, while Ward 1 candidates largely belong to a demographic — Yale students and alumni — that does not often remain in New Haven after graduation. A candidate’s professed commitment to the city is a common subject of discussion, with students speculating on whether the candidate is running out of genuine interest in New Haven or for personal gain. Long-term incumbency in the ward after graduating seems to indicate a candidate’s genuine desire to serve Ward 1 and New Haven.

For Stark, the incumbency effect was a real and important factor in the primary. He noted that there is an innate challenge in opposing Eidelson, who can point to her record in the city as evidence of her abilities.

And Eidelson’s record is not inconsiderable. As chair of the Youth Services Committee, she coordinated the creation of the New Haven Youth Map, an online resource that catalogues youth programs across the city. Eidelson also played a leading role in establishing the first student elections to the Board of Education in June. Earlier this year, she was elected the third officer of the Board of Alders, making her the first Ward 1 alder in at least a decade to attain a board leadership position.

“I think [the incumbency effect] is the ability to point to things that you may or may not have done in office, to point to titles that you may have,” Stark said. “People who voted for her on the basis of experience were certainly voting for her for the right reasons.”

In some ways, the September primary was atypical. Normally, incumbents enjoy higher name recognition and stronger funding networks than do challengers, according to political science lecturer Cynthia Horan, who teaches a seminar on urban politics. But over the course of the campaign, Stark raised 10 times the amount of money that Eidelson did. And two surveys in the News over the past year have indicated poor name recognition for Eidelson — an April survey found that only four of 37 students could name her as their alder.

At the same time, though, Horan said scholarship indicates that incumbents often benefit from low turnout: a notable advantage in September’s primary, in which only about 10 percent of Ward 1 residents voted. If this model holds, poor turnout may have been one of the keys to Eidelson’s success.

And as Eidelson heads into the general election against Republican Ugonna Eze ’16, her incumbency will likely influence voters once again. She said her record has proved an important benefit to her campaign. Having a history of success in the city, she said, gives her a strong base to stand on during her conversations with students.

“I definitely think it’s helpful, when I’m talking with students, that I’m able to talk about what I have actually done since they elected me,” Eidelson said. “There’s less speculation that voters need to do about whether or not I’ll be effective, about whether or not I’ll follow through on my commitments.”

Eidelson added that having a strong record can eliminate much of the uncertainty present in elections, where candidates often make promises without any way to guarantee they will reach fruition. Her four years in office, she said, prove that she has the ability to deliver her goals if elected to a third term.

Eze acknowledged that he will have to grapple with Eidelson’s record during his campaign, which he said makes standing against her all the more difficult. Still, he expressed confidence about his chances. He called incumbency a “double-edged sword,” explaining that while incumbents can take credit for the progress made during their term, they must also bear responsibility for their failures. He suggested that Eidelson’s perceived disengagement with campus, for example, will hurt her in November.

Eze dismissed the idea that Eidelson’s plethora of endorsements will swing the scale in her favor. Though as a Republican he anticipates receiving few, if any, endorsements from city officials, he said his campaign is all about challenging the status quo.

“I think voters at the end of the day are picking between two candidates, not the people who may or may not come out and endorse them,” he said. “What matters is your ability to mobilize and inspire people to vote for you in Ward 1.”

GETTING OUT THE VOTE

Outside the boundaries of Yale’s campus, too, the issue of incumbency casts a long shadow. In the 2013 aldermanic elections, for instance, all seven incumbent alders who faced challengers prevailed; in the citywide primaries in September, six of eight incumbents emerged victorious.

One of the victorious incumbents in 2013 was Ward 22 Alder Jeanette Morrison, whose constituency encompasses much of the Dixwell neighborhood as well as four Yale residential colleges. Morrison, who herself won her seat two years earlier by defeating the incumbent Greg Morehead, said incumbency can prove invaluable for candidates.

Morrison explained that alders are often judged by their records — alders with good records, then, can be difficult to beat. In her first term, she said, she gave her constituents reason to trust her as a community leader by making sure to respond to calls and emails. Morrison also pushed for popular neighborhood initiatives during her first term, including the long-delayed reopening of the Q House, a shuttered neighborhood community center. Though the Q House has yet to reopen, the issue has helped Morrison — along with other alders, including Eidelson — rally a base of support in the city.

But incumbency isn’t always advantageous, Morrison added; a poor record can come back to haunt you.

“If you’re an incumbent who’s been doing your job, it’s going to make it hard for the challenger,” Morrison said. A record of incompetence, on the other hand, will cause greater hardship for incumbents than would a blank slate. In those cases, she argued, “it’s going to take some courageous conversations to talk with constituents about your role.”

Darnell Goldson, a former Ward 30 alder and current candidate for one of two newly created elected seats on the Board of Education, echoed Morrison’s ideas, adding that a candidate’s legislative record in office is less important than his record as a community figure. Politics is all about personal relationships, he said: an alder must be constantly present in the ward for incumbency to augment his or her chances of re-election.

But Goldson said the most important factor in an election is a candidate’s ability to get out the vote. He attributed his 2011 defeat, in which he lost as an incumbent to challenger and current alder Carlton Staggers, to his opponent’s superior efforts to mobilize voters.

Indeed, Goldson suggested that incumbents may actually have a harder time getting out their vote than do challengers — pushing back against Horan’s evaluation of the scholarship surrounding incumbency. A false sense of security, or a belief that the incumbent already has the election in the bag, can cause voters who would normally cast their ballots for the incumbent to skip the polling place altogether, he said. Voters who support a challenger, meanwhile, have a greater competitive impetus to go to the polls. Part of the difficulty he faced in rallying voters in 2011 should be ascribed to this phenomenon, Goldson said.

Ward 12 Alder Richard Spears, who lost his primary in September but has vowed to run as an independent in the general election, expressed similar views. As alder, Spears has had one of the lowest meeting attendance rates on the board, a record which critics have latched onto during his re-election campaign.

Spears rejected the idea that an incumbent’s legislative record is — or should be — the determining factor during an election. He said that an alder’s job extends beyond City Hall, and voters should consider all parts of the alder’s performance, especially his or her presence as a community figure in the ward.

“You can always count attendance, but you can’t count [the] phone calls and deaths and shootings that I’ve had to address,” he said.

UNIONS: AN ELECTORAL JUGGERNAUT

At the center of New Haven politics lies an institution fairly distinctive to the city: the UNITE HERE union coalition. The unions hold enormous sway over the city’s political process in a system that, for some, seems a vestige of a past age.

“The Democratic Town Committee has 1960 policies for the 21st century,” Spears said. In 1960, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s Democratic machine orchestrated a monumental vote-pulling operation that played a major role in John Kennedy’s victory over Richard Nixon. Spears suggested with this parallel that the unions’ role in New Haven might not be so far off from that model of machine politics.

Though historical records suggest that incumbents do enjoy a certain advantage in re-election campaigns, New Haven’s 2011 elections departed from the norm. Of the 12 alders who faced challengers in their bids for re-election that year, eight lost. Seven of those eight opposed union-backed challengers, and the four victorious incumbents were union-backed. Ward 23 Alder Yusuf Shah planned to run as an independent after the Democratic Party endorsed his challenger. He later decided to drop out as a result of the amount of union money spent on his opponent’s — Tyisha Walker, the current president of the Board of Alders — campaign.

The union successes in the 2011 election are made all the more remarkable in light of the fact that City Hall had backed many of the defeated incumbents. The re-election of then-Mayor John DeStefano Jr. showed that City Hall certainly retained some sway over city politics, but other election results proved that union power had made City Hall’s influence subordinate. With the 2011 landslide, UNITE HERE came to control a large majority of the Board of Alders.

To some participants in New Haven politics, the union coalition possesses strength enough to counteract the incumbency effect.

“[UNITE HERE] is a powerful organizing force, and I think they’ve proven that they’re able to mobilize and win elections in a way that I think is stronger than incumbency,” Stark said.

He added that the only unsuccessful union-backed campaign he could recall was Ella Wood’s ’15 in Ward 7, where she suffered a heavy defeat to then-sitting alder Doug Hausladen ’04 amid controversy surrounding Wood’s residency in the ward.

Stark said the 2011 sweep and the victories of union-backed candidates Jill Marks and Gerald Antunes over incumbents in September demonstrate the power of the union coalition. According to Stark, union power exceeds the influence of incumbency.

Union influence flows from several sources. UNITE HERE has proven extraordinarily adept in recent years at mobilizing a network of volunteers to bring residents out to the polls. Unions also wield considerable fundraising power. Further, union-backed candidates can typically enjoy the endorsements of the union-backed alders already sitting on the board.

Spears, who fell to Antunes by an 82–18 margin in September, echoed Stark’s sentiments. Spears said the Local 34 union, a member of the UNITE HERE coalition, pervades the political process. Democratic ward committee chairs, he said, are “dominated” by Local 34; he added that the union will not hesitate to endorse a challenger if they believe the incumbent is not aligned with their own interests.

“If [incumbents] aren’t practicing the policy that’s backed by the unions, they don’t get a bankroll,” Spears said. “I had a committee of three people on the campaign. They had 20.”

Ward 28 Alder Claudette Robinson-Thorpe’s campaign, Stark said, illustrates union influence in the electoral process. Robinson-Thorpe came to power in Ward 28 in 2009, and retained her seat as a union-backed candidate in 2011 and 2013. But in January 2014, she joined with six other alders to form the People’s Caucus, aiming to counter union influence on the Board of Alders. Days later, a union-backed challenger, Ward 6 Alder Dolores Colón ’91, unseated Robinson-Thorpe as chair of the alders’ Black and Hispanic Caucus by a vote of 10–4.

In the 2015 primary campaign, 18 months after Robinson-Thorpe split with the union, the coalition supported challenger Jill Marks, the wife of Rev. Scott Marks, co-founder of the Connecticut Center for a New Economy, a powerful union-affiliated group. Despite receiving endorsements from Mayor Harp, state Rep. Robyn Porter and the AFSCME union, Robinson-Thorpe fell to Marks by a 55–45 margin.

In an interview with the News, Robinson-Thorpe emphasized the political importance of an on-the-ground organizational effort. She said she had no access to the kind of vast resources that Marks could easily tap.

“They had 100 people walking my ward trying to dethrone me,” she said. “You’ve got to have troops on the doors. They had the whole union behind them, and I didn’t have that many people. If you [have] 300 to one, of course you’re going to win.”

Many of Marks’ campaign volunteers, Robinson-Thorpe said, didn’t live in the ward, or in New Haven at all, instead hailing from outlying towns and suburbs like Guilford, Branford and East Haven. With those volunteers, Marks was able to blanket the ward in a way that Robinson-Thorpe couldn’t. Personal factors played a role, too: shortly before the primary, Robinson-Thorpe broke her leg and ankle, rendering her unable to complete a careful canvassing of the ward. Had she been fully mobile, Robinson-Thorpe said, she would have prevailed.

Robinson-Thorpe said Marks’ superior ground strength, a product of her union backing, delivered her victory in the primary. Robinson-Thorpe has yet to decide whether she will run as a petitioning candidate in the November general election. If she does, she will face a formidable challenge.

***

Now that the Ward 1 primary is over, the prospect of a three-way race — which would have been a real possibility had Stark bested Eidelson in the primary — has dissipated. Eze has now set his sights on the general election. He said that he will focus on exploiting Eidelson’s weaknesses, particularly what he called her disengagement on campus. Eze aims to maintain an active presence on campus, and to that end plans to attend Yale football games and has hosted events to discuss policy proposals and his vision for the Ward 1 alder’s role in the city.

But Eze faces an uphill battle. Incumbency and union backing have proven their strength in recent years, and they are all the more powerful when they coincide, as they do for Eidelson. Eze may well prevail — his connections on campus and anti-status quo message could win over enough voters to overwhelm Eidelson. A victory for Eze, though, seems unlikely in a city where incumbency and union backing each play their crucial role in determining the power structures that dominate city government.

Still, Eze’s very campaign predicates itself on its outsider status. As unlikely as a Republican, non-union-backed, non-incumbent’s victory in New Haven might seem, Eze — armed with dozens of enthusiastic volunteers and a reformist zeal — says he is ready for the challenge.