As the nation focuses its attention on campus sexual misconduct, students, administrators and activists alike turn to data for answers. But low reporting rates mean most stories go untold — leaving universities largely unguided in their efforts to address a widespread yet simultaneously highly particular problem.

On Dec. 2, 2014, thousands of students, faculty and staff in Woolsey Hall burst into applause as former United States President Jimmy Carter confronted University President Peter Salovey about Yale’s sexual misconduct policies.

“I read one article on the way up here … and it pointed out that Yale has in previous years … [students who] had been guilty or admitted that they committed sexual assault, and they had not been expelled,” Carter said.

Carter was citing an August 2013 Huffington Post article about Yale’s controversial July 2013 Report of Complaints of Sexual Misconduct. While the report concluded that four students were found responsible for engaging in nonconsensual sexual acts, none of them had been expelled, and only one was suspended.

Carter’s remark soon spread across the Internet, from Twitter to Inside HigherEd and back to the Huffington Post. But Yale was quick to distance itself from the criticism.

Karen Peart, the University deputy press secretary, told the News later that day that the original Huffington Post article had not correctly stated the facts. Indeed, the article states that Yale “found six students guilty of ‘nonconsensual sex,’” but the language of the report itself points to “certain nonconsensual acts during otherwise consensual sexual activity” in several of the cases. The cases in question involved violations of Yale’s more “stringent” definition of consent as positive, voluntary and unambiguous, Peart said.

But the conflicting explanations reached by Yale administrators and Carter indicate a problem beyond punishment or definition. Instead, they illustrate how even experts in sexual misconduct policy can be confused by the limited data on campus sexual misconduct.

Indeed, as Yale — and campuses across the country — races to address a burgeoning nationwide conversation about sexual assault, policymakers, politicians, university counselors and students alike are faced with a lack of quantitative information. Instead, vague reports and anecdotes dominate the conversation about a problem that, more often than not, occurs behind closed doors.

Administrators acknowledge their inability to know either the true incidence or reporting rates of campus sexual misconduct. Left out of every Semi-Annual Report of Complaints of Misconduct — which lays out all the complaints that come to the University’s attention in a period of six months, as well as their outcomes — are the students who do not tell their stories, at least not to administrators or police.

“[Sexual assault] goes on at all the universities,” Carter said. “But I think the main thing is to let the students know what is going on and teach them if they want to know what can be done in case there is a case of sexual assault.”

The question, then, is this: What exactly is going on?

NUMBERS MATTER, TO A DEGREE

Yale is trying to find out.

On April 2, the University released its iteration of the Association of American Universities’ campus sexual climate survey, one of the largest efforts ever to compile information on campus sexual assault. The survey encompasses several topics related to campus sexual climate, including students’ perceptions of campus resources, their opinions of fellow students’ and administrators’ likely reactions to a report of misconduct, and their own experiences with stalking, intimate partner violence, sexual harassment and sexual assault since arriving on campus.

The results, which will be published in the fall, will offer a glimpse into problems at Yale and across the nation.

But even before a new set of information arrives, Yale already stands ahead of the curve.

An August 2013 statement by the University said that Yale was the only institution “to [its] knowledge” to release a comprehensive log of the complaints that came to its attention. Yale also formed one of the nation’s first campus adjudicative bodies specifically dedicated to cases of sexual misconduct in 1978.

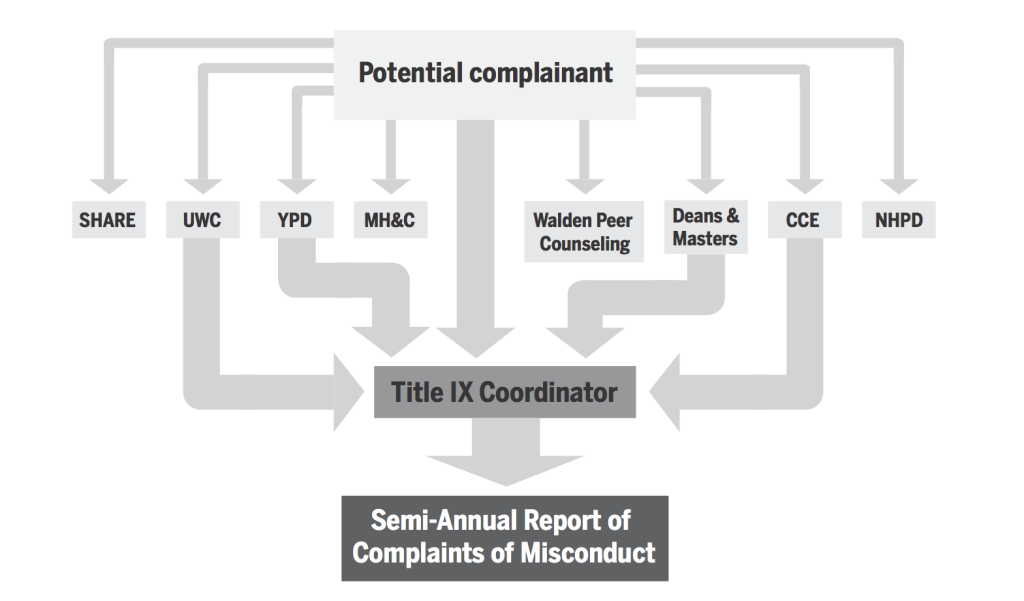

Over time, Yale has worked to build an environment where reporting is an accessible option, Assistant Dean of Student Affairs Melanie Boyd said. Yale’s Sexual Misconduct Response website lists nine avenues through which a student could make a report, three of which also function as formal complaint mechanisms. There is no right or wrong entry point to the system, Boyd said.

But all of the University panels and reporting mechanisms have done little to diminish confusion surrounding the prevalence of sexual misconduct.

Yale’s semi-annual reports reveal nothing about incidence or reporting rates. The number of reports of sexual misconduct made to the University has increased steadily over the years, from one undergraduate complaint of sexual assault, stalking or intimate partner violence brought before the Executive Committee in 2005–06, to 46 such cases brought to the University-Wide Committee on Sexual Misconduct or Title IX coordinators in 2013–14. However, University Title IX Coordinator and Deputy Provost Stephanie Spangler has repeatedly noted that it would be a mistake to extrapolate trends from the relatively small body of data available. As a result, the University’s true incidence rates remain unknown.

Meanwhile, data that does purport to represent incidence rates has come under attack.

A 2007 study sponsored by the Department of Justice concluded that one in five women will be sexually assaulted before graduating from college. But in 2014, another study released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics put that number at just 0.6 percent of college-age female students nationwide.

This discrepancy has cast the legitimacy of statistics like “one in five” in doubt, said Joe Cohn, legislative and policy director at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. Cohn said he is “deeply skeptical” of the 2007 results.

“Advocates often cherry pick which study they want to cite, depending on whether it supports their worldview,” Cohn said.

Because of the different methodologies used, though, Christopher Krebs, co-author of the 2007 Campus Sexual Assault Study, warned against viewing the one-in-five statistic — or indeed any broad statistic — as indicative of any individual school’s condition. His study used data from two large public universities while the 2014 study relied on data from the National Crime Victimization Survey.

“I don’t think the data from those two schools [in my study] are necessarily useful if I’m an administrator in another state or across the country or of a totally different ilk,” he said. “I think that sexual assault is something that probably happens at all schools, but is unique to each school.”

Even statistics from the Jeanne Clery Act of 1990 — whose reporting parameters are standardized by law — do not paint a complete picture of the size of the sexual assault problem. Under the Clery Act, schools are required to disclose information about crime on or near their campuses, which are defined through certain predetermined geographic boundaries. But even these distinctions can provide muddled information: An incident on one side of the street may have to be reported, while an incident across the street would not, Boyd said.

Still, Lynn Langton, co-author of the 2014 BJS study, said generalized data can be important for benchmarking purposes if examined alongside more specific data.

“An individual school should not … assume that the rates we’re putting out are what they would expect to see at their school as well,” she said. “But if a school conducts a campus climate survey … they can use the national data to understand whether what they’re seeing on their campus is consistent with the nationwide picture, or whether there are some variations that might be important for them to better understand.”

BEYOND THE DATA

If there are variations on Yale’s campus, some might be the result of policies the University has put in place to foster an environment that encourages reporting. Beyond the wide range of formal and informal options available to potential complainants, Yale has worked to ensure that the process of filing a report or complaint is as much in the victim’s control as possible.

The distinction between making a report and filing a complaint is a critical one, Boyd said. For example, making a report — in other words, telling somebody of a distressing incident — in no way obliges a student to pursue disciplinary action through a complaint. A Title IX coordinator may need to take independent action if there is an acute threat, but even then the student is not required to participate. At some other schools, Boyd said, fewer options exist.

In addition, students may drop out of the complaint process at any point. Even if they initiate a formal complaint, they are never forced to cooperate and in fact do not even have to attend their own UWC hearing, said UWC chair and ecology and evolutionary biology professor David Post. Sometimes a Title IX coordinator will serve as the complainant if the person alleging harm does not wish to directly participate, he added.

Last October, the UWC also eliminated time limits for filing a complaint, so that any community member who wishes to bring a complaint may do so, even years after the incident. The purpose of the change, Post said, was to allow complainants sufficient time to process their experiences.

Alexa Derman ’18, public relations coordinator for the Yale Women’s Center, said that although there is still work to be done, Yale as a community seems to do better than most in encouraging reporting. She said this could be a result of “pioneering programs” on campus like the Communication and Consent Educators program, increasing University responsiveness to issues of misconduct, as well as student activism that tries to keep the conversation open.

“From the number of programs to the number of individuals delegated specifically to these issues, dialogues about sexual misconduct are never far from the campus radar,” she said. “I think as a result, there’s a higher-than-average amount of awareness, both of the issue and of the possible avenues of response.”

Corey Malone-Smolla ’16, a CCE, agreed. While there is a great deal of conversation and activism about sexual misconduct on other campuses, she said — citing what she has heard from friends at the University of Virginia since the publication of the now retracted Rolling Stone article “A Rape on Campus” — few other universities seem to have institutionalized prevention and awareness in the way Yale has.

Compared to its peer institutions, Yale also has a larger number of community members with obligations to report cases of sexual misconduct brought to their attention, Boyd said. Under Title IX law, anyone whom a student could reasonably expect to have authority to address an issue of sexual misconduct is obligated to report the alleged occurrence to a University official or Title IX coordinator. For example, if a student disclosed an alleged incident of sexual assault to their professor, the professor would have to relay that information to a Title IX coordinator. According to publicly available information on Harvard’s and Princeton’s sexual misconduct policies, some faculty and specially designated students there have reporting obligations. But Yale has an unusually high number of students in formal leadership positions who fall into that category, Boyd said, and so students may be more likely to find their way into making a report.

In addition to faculty and administrators, several groups of students on campus have reporting obligations as well. Freshman counselors, CCEs and freshman pre-orientation leaders are all required to report any account of potential misconduct they hear, Student Affairs Fellow Hana Awwad said. The Title IX coordinator will then reach out to the student and offer support.

A POORLY KNOWN, FLEXIBLE SYSTEM

Even so, administrators agreed that sexual violence remains a stubbornly underreported crime at Yale. And the effectiveness of Yale’s specific policies to encourage reporting is unclear.

“I did know that [the Sexual Harassment and Assault Response & Education Center] existed,” said Eden Ohayon ’14, who filed a formal complaint with the UWC in May 2014. “But it had to be explained to me what all of the different kinds of complaints you can file — Title IX coordinator, UWC formal, UWC informal — were. I didn’t know all of that. I learned about that through the SHARE counselor, and I had to read over all the procedures.”

For students who identify as survivors, the multiple avenues that Yale offers to file a report are commendable — if people know about them. Four of the five students interviewed who described themselves as victims of sexual assault said they were not initially familiar with the avenues available to them to discuss their experiences. One student knew only about SHARE. Another only remembered the frozen yogurt consent workshop run by the CCEs during freshman orientation.

The question of reporting obligations drew more mixed reviews.

The purpose of these obligations is to ensure that everyone who may have experienced sexual misconduct knows the options available to them, Boyd said, adding that even if students decide they do not want to speak with the Title IX coordinator who has reached out to them, just the experience of having help offered can be valuable.

But some students, advocates and researchers interviewed emphasized the importance of respecting victims’ privacy wishes.

“I think to get an email directly from the administration about something you clearly have opted not to talk about with the administration can be surprising, and I think for some people it might not be a super welcome surprise,” said one student who chose not to report her incident because she did not believe it would help her healing process.

She added that if a CCE or someone else overheard a conversation that triggered a reporting obligation, it would be fine for the CCE to approach the person to ask if they wanted to be referred to other options — but if the person said no, that should be the end of it.

Callie Marie Rennison, associate dean of faculty affairs at the University of Colorado Denver and a researcher who has studied sexual violence research methodology, said having a hard rule about reporting obligations minimizes victims’ autonomy.

“It’s like going to a funeral. Twenty people are in the room — one guy is laughing, one guy is sobbing uncontrollably, and somebody else is indifferent. Everybody handles trauma very differently,” she said. “We just have to accept that and allow people to handle that they way they need.”

Boyd said that Yale’s focus is the same: to allow a potential complainant to pursue his or her own path. For example, it would be very rare for someone to be blindsided with an email from a Title IX coordinator, she said, because whenever possible, the reporter will tell the person that they are going to report and explain what will happen next. Additionally, there are several groups exempt from reporting obligations on campus, such as SHARE, Walden Peer Counseling and the undergraduate Sexual Literacy Forum.

Malone-Smolla said that though some people who have approached her to talk about sexual misconduct have been surprised to hear that she is a mandatory reporter, they are usually still willing to talk after she explains what that mandatory reporting entails.

“I say that all it looks like is that a Title IX coordinator will send you an email and say, ‘These are the resources on campus; feel free to talk to me,’” she said. “I always tell them, ‘You can simply ignore that email, delete it, and that will be the only kind of contact that will happen between you and them.’ Because if they’ve already come to me wanting to talk about it, something like that doesn’t usually deter them once they actually know what [reporting] looks like.”

And if a student is extremely adamant that they do not want to hear from an administrator, that, too, can be taken into consideration. Yale College Title IX Coordinator Angela Gleason said if that is the case, she tries to respect the student’s wishes as much as possible.

Barring a situation where leaving an incident unaddressed would compromise campus safety, Gleason said, she will often work with Spangler to look for other ways to make sure the student knows about available resources.

“These [reporting requirements] are the guidelines we’re working by, but we do everything we can to take into account extenuating circumstances,” Boyd said.

INVISIBLE BARRIERS

Ultimately, conversations with students who identify as survivors revealed that the most important barriers to reporting are not unique to Yale.

For one student who said she was raped her freshman year by someone with whom she shared many mutual acquaintances, the hostile responses of her friends kept her from reporting for a long time. They would constantly tell her “not to make things awkward” and to pretend nothing had ever happened, she said. By the time she came to see the incident as sexual assault months later, she said, she was too exhausted by the experience to pursue a complaint.

Ohayon said she struggled with self-blame in the months after her experience. Her alleged attacker was also a friend at the time, she said, and she took that fact, as well as her own level of intoxication to mean that she was responsible for having sex. It was only after she realized she was not at fault that she filed a complaint with the UWC four months later, she said. The UWC later found the respondent not responsible for sexual assault.

Another student said she chose not to report an alleged rape during her freshman year because reliving it through a report or complaint would not help her achieve her goal of feeling better or of finding her place at Yale.

“I think people think about it almost a little too rationally in the sense that someone did something wrong to you, so don’t you want to pursue them?” she said. “You can imagine if you get mugged that a big priority is to get your stuff back and get that person punished. But here I think what [the incident] took away from me is … a sense of faith and security. That’s just not something you get back by opening a complaint.”

She emphasized that although she did not know about SHARE or the possibility of an informal complaint until some time after her incident, knowing about such options from the beginning would not have changed her thought process. She would have arrived at the same conclusion — a desire to move on and protect her social life — at any university in the country, she said.

In many ways, the stories of these students reveal that barriers to reporting are not just matters of poorly shaped policy but rather community-based obstacles.

While her own close friends were supportive after her alleged assault by a friend at the time, Ohayon said she worried about backlash from mutual acquaintances, especially given the involvement of alcohol in her case and possible disagreements about her ability to give consent.

“We could definitely do a better job at Yale of taking [cases involving alcohol] seriously and of talking about what consent really means, instead of just parroting back a definition that we were told by CCEs as freshmen,” she said. “Everyone agrees with it on paper, but when we’re asked to make judgments about certain situations, I feel like that’s where opinions aren’t as consistent and people tend to be more judgmental.”

Others, however, noted that community pressure can go the other way, in pushing people to report when they do not want to do so. One student said she told a few close friends about her alleged rape after it happened, and a few of them encouraged her to report in order to protect other women from being similarly assaulted.

But their encouragements did not take into account what she perceived would be the great personal sacrifice required by reliving the incident, she said. Even though her community was supportive and policy was not a barrier, she chose not to report.

“I just don’t think there was much that Yale could have done to make me tell them about it,” an anonymous student said. “Speaking to the question of that initial decision to even pursue avenues, it’s not clear to me that Yale could do a significantly better job.”

WHAT COULD MORE DATA DO?

Even so, Yale is trying to gather more information through the AAU survey in an attempt to better focus its efforts against sexual misconduct. But in any data set, there remains the potential for misinterpretation.

In the University’s semi-annual reports, confidentiality concerns mean that each complaint is summarized in only a few broadly cast sentences. Differences in interpretation are inevitable, Boyd said, adding that administrators try to write the summaries in ways that remind people not to assume they know what a certain experience entailed just by reading the report.

“Even when a specific act is clear, people need to be careful not to jump to conclusions,” Boyd said. “Each case of sexual misconduct has its own complexities.”

Still, administrators can learn from readers’ confusions as well. Because UWC procedures are complex, Post said, educating the community about them can be challenging. But Spangler said the semi-annual reports have raised community awareness about Yale’s sexual misconduct procedures, and the conversations — and concerns — the reports generate have been informative in their own turn.

“The broad community discussion … serves as yet another source of information, as we seek to improve not only our procedures but also our ways of communicating about them,” Spangler said.

She added that while she cannot predict how the AAU survey data will inform Yale’s thinking until the data has been analyzed, she offered a hypothetical scenario: If the data revealed that students in a specific school or community were less likely to report misconduct than the general population, for example, the University could target concerns specific to that community by offering special programming or recruiting more UWC members from that school.

But even with more information, administrators should be careful when deciding how much to disclose, said Alison Kiss, director of the Clery Center for Security on Campus. She defended,for example, the Clery Act’s requirement that timely campus-wide alerts be sent only when there is an ongoing criminal threat. That distinction limits the amount of information sent to the community and helps protect the privacy of the victims involved, she said.

“It’s a difference between need-to-know for safety and need-to-know just to be in the know,” she said. “I’m often concerned about the second case, because I think it could have a chilling effect, especially if it’s the type of environment where the campus is very aware of what social events were happening this weekend and may be able to identify the victim.”

ONE IN FIVE?

In many ways, Yale has been a leader in the field of sexual misconduct. Over 30 years ago, the University was the defendant in the trailblazing case Alexander v. Yale, which established sexual harassment as a violation of Title IX.

But even three decades on, dealing with sexual misconduct remains a figurative minefield for universities.

“The definitions [of misconduct] are controversial, the way we measure it is controversial, getting people to come forward is difficult, and so is getting people to even identify what happened to them as violent,” Rennison said. “This area has every research challenge associated with it.”

The lack of data surrounding the problem of sexual violence is problematic, as it hinders administrations’ abilities to tailor programming and prevention to the needs of their own campuses.

But at the same time, many of the broader challenges campuses face are not dependent on numbers and graphs but on community perceptions — perceptions that are, by all accounts, widespread.

“We should always be transparent about the fact that the data just isn’t good enough to tell us exactly how many attacks are taking place or to be able to chart trends from year to year,” said Scott Berkowitz, the founder and president of the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network. “But I think that even the most conservative estimates are that there are many, many thousands of sexual assaults taking place on campuses every year. In terms of whether we’re going to focus on it, it doesn’t really matter what the exact number is.”