Last May, as seniors gathered at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina for their time-honored, week-long celebration before commencement, a female student and a male student found themselves a few feet away from each other on the beach. This encounter would have been just like any other that week — except that these two students were barred by the University from interacting with one another.

Several months before, in February, the female student had filed a formal complaint with the University-Wide Committee on Sexual Misconduct alleging that, in the midst of an otherwise consensual sexual encounter, the male student had engaged in nonconsensual anal contact with her.

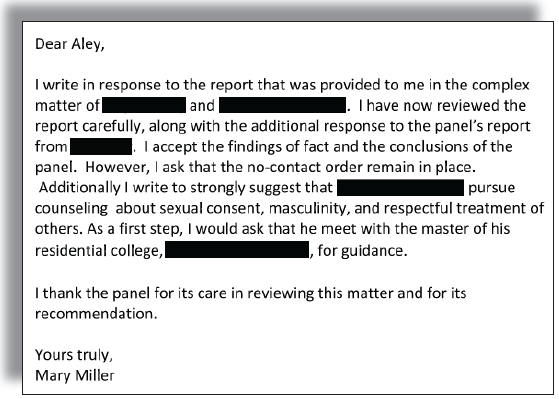

After roughly two months, in which an independent fact-finder investigated the claim and a UWC panel held a hearing, the five-member panel determined that the male student had not violated Yale’s sexual misconduct policies. It did not recommend any follow-up measures. Then-Yale College Dean Mary Miller upheld the panel’s findings, according to her written decision, which — along with the fact-finder’s report, the panel’s report and the complainant’s response to the panel’s decision — was provided to the News.

But at the request of the female student, Miller asked that the no-contact order between the students, which had been registered when the formal complaint was first filed, remain in place. She further recommended that the male student meet with his residential college master and pursue counseling about sexual consent, masculinity and respectful treatment of others.

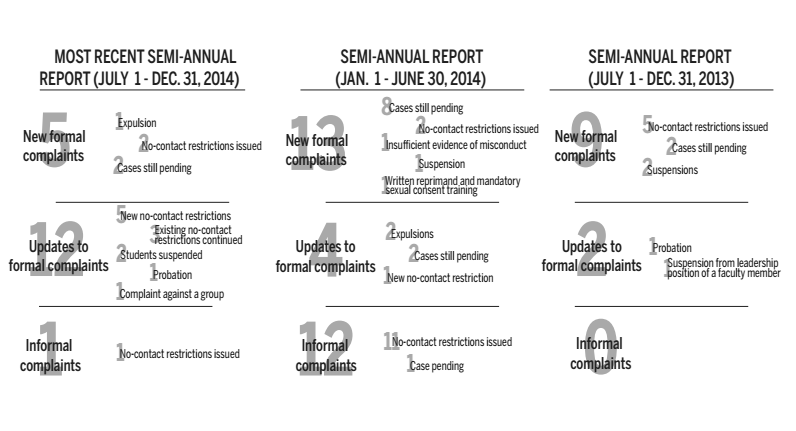

No-contact orders are a common outcome of sexual misconduct complaints that come before the University. Among new formal UWC cases included in the most recent semiannual Report of Complaints of Sexual Misconduct, every case that is no longer pending resulted in either an expulsion or a no-contact restriction. Across all seven reports released since the first such summary of complaints was published in January 2012, virtually every case that did not end in the expulsion, suspension or probation of the respondent resulted in a ban on contact between the parties involved.

At a University with 11,250 students — on a central and medical campus that is smaller than 350 acres — it is difficult to avoid running into someone. And when most complaints occur between parties who know each other, no-contact orders are simultaneously fundamental to the integrity of a formal disciplinary hearing and difficult to enforce. Using documents from formal complaints of sexual misconduct, interviews with parties involved in these cases and University officials charged with administering these orders, this story examines the purpose and the efficacy of barring contact between members of the community on opposite sides of assault complaints.

SAFETY AND WELLBEING

No-contact orders are put in place between a complainant and a respondent the moment the respondent is notified of the formal UWC complaint, said UWC Chair David Post, who is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. The order, which is an interim protective measure, remains in place until the case is finalized. Among the possible sanctions it may hand down, the UWC has the option of specifying that the order continue after the case has been finalized.

While no-contact orders vary in details and scope, they at a minimum typically include restriction on physical, verbal and virtual contact between the parties, according to Yale College Title IX Coordinator Angela Gleason, who supervises the implementation of no-contact orders for undergraduates.

University Title IX Coordinator and Deputy Provost Stephanie Spangler said these orders are vital to the safety and wellbeing of students who choose to report sexual misconduct.

“No-contact directives are among the actions that we can take to ensure that complainants are — and feel — safe, are free from retaliation for bringing a complaint and can pursue their Yale activities free from sexual discrimination and misconduct,” Spangler said.

She added that contact restrictions may also result from informal complaints and reports to the Title IX coordinator, which, unlike formal UWC proceedings, do not typically result in disciplinary action.

THIRTY FEET APART

After the encounter at Myrtle Beach — the precise details of which are disputed by the parties involved — the female student wrote an email to then-UWC Chair Michael Della Rocca, a philosophy professor, requesting that he remind the male student of the no-contact order.

The complainant explained that they were both at Myrtle Beach with the senior class and that she felt some of his behavior was violating the order.

“I know we are not on Yale campus, and the no contact order is very vague, but his behavior is making me very uncomfortable,” she wrote in the May 9 email.

There had been no verbal contact, she continued, but the male student was approaching her in a way that she felt violated her boundaries. Using language that suggested his behavior was chronic, she said he would sit on the beach within six feet of her. She claimed that he would not leave areas that she had occupied first, and that while she had been making efforts to avoid him, she felt he was not being similarly conscientious.

“I would like to clarify in distance the number of feet we stay away from each other, and I think 30 feet would make me feel safe,” she wrote. “I would also like to clearly establish that the person who is in a location first (e.g., a computer cluster, a college common room) can stay, and the person who gets there after will move the set distance away.”

In an interview last week, the male student involved in the complaint said he had never intentionally violated the no-contact order and in fact had not even been aware of the female student’s presence when he sat down near her at Myrtle Beach. The female student told the News that the respondent should have done more to avoid her.

When she was first notified of the order, it included no mandate for a specific distance between her and the respondent, the female student said, leading her to request a more strictly defined boundary.

Indeed, the order’s limits were evident from the moment of its enactment: She and the respondent happened to be in a class together that semester. As part of the no-contact order, administrators thus required that the male student enter the lecture hall through a particular door and sit on a particular side of the room. But according to the complainant, these rules were not always abided by, prompting her counselor at the Sexual Harassment and Assault Response and Education Center to write to UWC officials.

The order, which the female student said was communicated verbally and through email and never outlined in an official notice beyond Miller’s recommendation, was “really, really vague.” It dictated no contact without specifying what counted as contact, she said, and so she took it upon herself to request the physical distance because she felt the current order was not giving her the space she needed.

While additional elements can be added to a no-contact order — Gleason listed the possibility of restricting individuals from visiting certain areas of campus, participating in certain student organizations or taking the same class — the two students in question were already enrolled in the same class at the time that the complaint was filed in February.

BOUNDARIES, VIOLATED AND MAINTAINED

The nature of the female student’s formal UWC complaint was that the respondent had repeatedly ignored boundaries she had set during the course of an otherwise consensual sexual encounter.

“In particular, the allegation is that [the respondent] had nonconsensual anal contact with [the complainant] even after she had clearly stated that she did not want to have such contact,” the panel report stated. “In addition, [the complainant] alleges that [the respondent] repeatedly acted against her request to be more gentle in his sexual behavior.”

Two days after the incident, the student met with a counselor at SHARE and decided to file a formal UWC complaint. After an investigation by an independent fact-finder, the UWC panel found the complaint was not substantiated.

Regardless, the female student said she felt violated by the experience, which undermined her sense of control over her own body and her space, the fact-finder’s report said. No matter the result of her complaint, she said, she wanted never to have to interact with the male again.

Then-Yale College Dean Mary Miller provides UWC Secretary Aley Menon with her final decision in a case involving two undergraduates. The decision was rendered April 23, 2014

But it was never clear to her what consequences, if any, would result from a violation of the order that was put in place as the sole mandate arising from the case.

In a May 10 response to the female student’s email, Della Rocca said he had emailed the male student to remind him of the no-contact order and specifically requested that he not come within 30 feet of the female student.

“I reminded him that there is only a short time until graduation and that it is in his interest and yours that the no-contact order be scrupulously observed,” he wrote.

But the female student said she does not know what would have happened had the orders not been scrupulously observed. If she had to guess, she would presume nothing, she said, because it did not appear that the male student had been punished for the incident at Myrtle Beach.

She acknowledged that Della Rocca had never explicitly said the male student had violated the no-contact order. He simply told her that he had reminded the male student of its existence.

Della Rocca did not return requests for comment.

Gleason said any intentional violation of a no-contact order is subject to discipline and may also be considered a form of retaliation. Acts of retaliation for complaints of sexual misconduct are explicitly prohibited under Title IX.

She added, however, that accidental violations may occur and that no-contact orders must occasionally be modified to adjust to new circumstances. Such situations are discussed with both parties before any changes are made, she said.

ENFORCING THE ORDER

“Honestly, the whole UWC process was the furthest thing from my mind [at Myrtle Beach],” the respondent in the spring UWC case told the News. “If I had actually been there second, that was my mistake, but there was no attempt to make any kind of contact or communication. In that case, I guess I must have been a little too close.”

He agreed, however, that there were never clear punishments outlined in case a violation did occur. The communications he received from Della Rocca were more of a reminder than a disciplinary notice, he said.

“It was basically them trying to make sure nothing escalates, just as a cautionary procedure,” he said. “It didn’t ever really feel like, ‘If you don’t comply, we’ll be forced to do so and so.’”

In fact, the male student said, he understood the entire no-contact order to be intended as a deterrent to escalation. He said he sympathized with the administration’s decision to impose contact restrictions, even though the UWC did not find him responsible for misconduct, adding that the restrictions were more of an inconvenience — for example, mandating he use a given door as opposed to another — than a punishment.

He added, however, that part of the reason he did not mind the restrictions was because he only had a few months left at Yale. The situation might be different for a student who would be on campus for a longer period of time, he said.

“In my particular situation, since there was really just one semester to go, it was just a question of avoiding until graduation this person I didn’t usually see anyway until graduation,” he said. “But if it happens to some sophomore who has to worry for two more years, I can see how it might be problematic, like if they both want to get into the same seminar.”

While no-contact orders are not designed to be a punishment, Gleason said, she can understand how they might be perceived that way.

“Restrictions on an individual’s campus activities requires ongoing awareness and care from everyone involved,” she said. “We work with complainants and respondents to implement plans which are comprehensive and viable.”

Still, she acknowledged that coordinating and enforcing no-contact orders on a small campus like Yale’s can at times be challenging.

The female student said that while she expects the University to exercise its administrative power to urge students to comply with no-contact orders, at the end of the day, “they are not the police.” While no-contact orders are a tool Yale can use to promote a safe environment for its students, she said, the onus is ultimately on the parties involved to enforce the orders.

“The whole situation is all very confidential, so it’s not like anyone would be able to enforce it besides the complainant and the respondent,” she said.

Another former UWC complainant, who also has a no-contact order in place against the respondent in her case, said she frequently sees her respondent around campus. He does not make efforts to leave when they are in the same room, she said, and she does not do so either. Their no-contact order does not specify a physical distance they must keep from one another, but rather bars “direct or indirect contact with each other while either remains a student at Yale University.”

She echoed the other female student’s comment that the parameters of the no-contact orders were never clearly delineated.

“No one ever spelled out what no contact looks like,” she said. “I don’t know what would happen if [the order] was violated, I don’t who I would contact, I don’t know what it would mean to have violated [the order]. If he came and sat at the same table as me in the dining hall, would that count? I don’t know.”

Still, she said, this ambiguity does not bother her, because the no-contact order never felt relevant to her case. Neither she nor the respondent had any desire to contact each other during or after the UWC proceedings, she said, so any possibility of genuine interaction was moot.

ROOM TO IMPROVE

A student who identifies as a victim of sexual assault — though she did not report the incident to University officials — said a no-contact order would have given her license among friends and peers to avoid the male student she claims raped her. She said she did not file a complaint initially because her friends insisted she had mischaracterized the encounter, and now because she simply wants to put the incident behind her.

Because her friends did not acknowledge her version of the events, she felt pressured to continue spending time with her alleged assailant in group settings. She coped with this pressure by abusing alcohol, she said. Ultimately she distanced herself from the social circle she felt had refused to validate her experience.

The first female student said that while her no-contact order did not protect her at Myrtle Beach, it did give her some peace of mind. It made her confident that she would never have to speak to the respondent again, even if he did not respect the physical restriction.

Although the female student did email Della Rocca, through her SHARE advisor, once in March to notify him that the male student was not complying with directions about behavior in their shared class, overall the arrangement worked out, she said. According to emails between the student and her SHARE advisor, in that situation also, Della Rocca contacted the male student to remind him of the no-contact order.

She said that while no-contact orders are good in theory, in practice they are not as effective as she would like. A way to increase their efficacy, she said, would be for the Title IX coordinator to lay out the parameters of the orders on a case-by-case basis, rather than issuing the generic no-contact instructions she felt she had received.

“These things should be set out on an individual basis,” she said. “Everyone’s situation is different, and everyone has different comfort levels.”

The male student also said he never sat down to discuss exactly what the orders would look like.

When asked about how the specifics of no-contact orders are outlined, Gleason said the orders are implemented on a case-by-case basis, and are always discussed separately with both the complainant and the respondent. Both parties are encouraged to keep in contact with the Title IX coordinator to report any concerns or request changes to the orders, she said.

Ultimately, the female student said, no-contact orders represent a powerful tool the University has to ensure the safety of students, independent of the conclusion of their formal complaints.

“They’re not the police, and it’s not their job to investigate criminal matters, but as a residential university they do have the responsibility to create a safe space for all students,” she said. “I think the no-contact orders are definitely a tool they can use to create a safe environment. They’re a good thing, but they’re just not practiced well.”