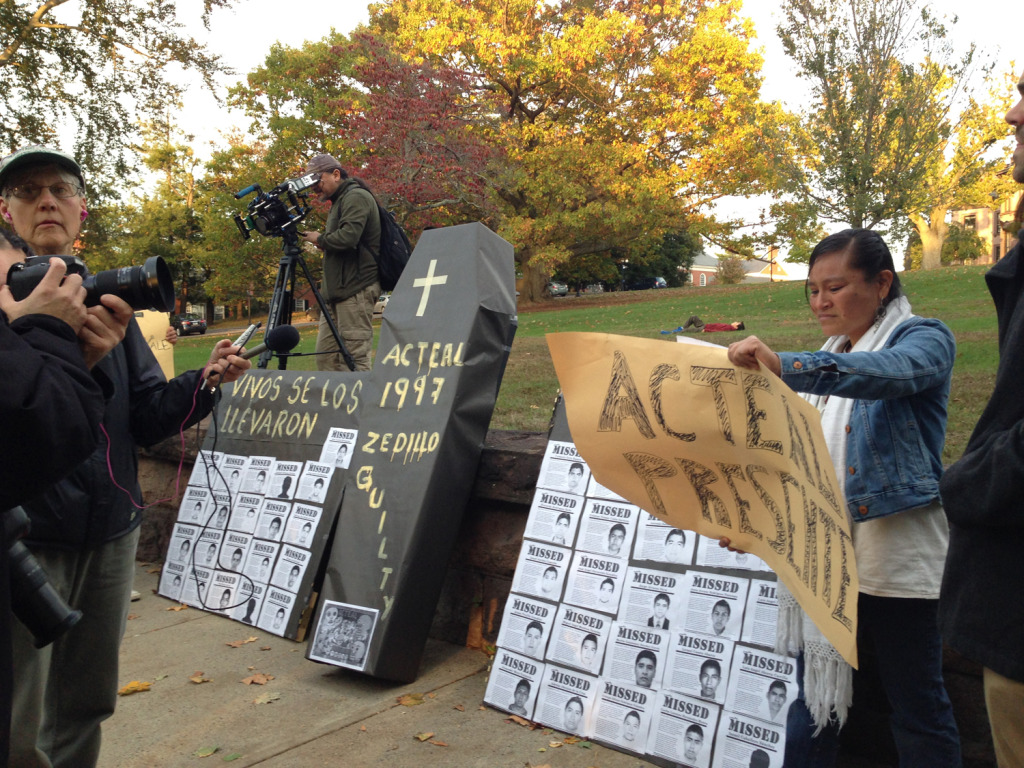

On Monday evening, a crowd of about 30 protestors gathered outside of Betts House on Prospect Street, near the Yale Divinity School. Armed with posters and a large paper coffin, the protestors shouted chants towards the building, which houses the office of adjunct professor and former president of Mexico Ernesto Zedillo GRD ’81, now director of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization.

The protest, organized by Unidad Latina en Acción , the Amistad Catholic Worker, Yale students and Mexican nationals living in Connecticut, denounced Yale’s employment of Zedillo. Their qualm with the former president stemmed from a 1997 massacre in the village of Acteal, Mexico, which occurred during his presidency. According to protestors, the Acteal massacre falls within a longer history of state-sponsored terrorism aimed at marginalizing members of the lower class in Mexico.

On Oct. 6, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case against Zedillo, ending a process that began in 2011 when 10 unnamed plaintiffs — who claimed to be survivors of the attack and families of those killed — filed a lawsuit against the former president for crimes against humanity.

In a press release following the Supreme Court’s decision, Zedillo’s lawyer Jonathan Freiman LAW ’98 expressed relief that the suit had come to a close. “Mr. Zedillo served his nation with ‘tremendous vision and courage,’ as President Clinton once noted. The calumnious claims against him are now put to rest,” Freiman said.

Despite the ruling, organizers of Monday’s protest called for continued action on the part of local residents, Yale students and University faculty to bring Zedillo to justice.

In addition to protesting the immunity granted to Zedillo by both the U.S. State Department and the University, the protest also called attention to the murder of two Mexican students and the abduction of 43 more from Guerrero, Mexico in late September.

Protestor Joe Foran, a New Haven resident, claimed that the crimes in Guerrero, which occurred at a protest against the Mexican government’s privatization of the education system, were another instance of the “state-sponsored terrorism” that occurred under Zedillo and, he said, continues to this day.

“They were taken alive — we want them back alive,” was one refrain protestors shouted towards Betts House.

Organizers said demonstrators and family members of the students fear that the Mexican police, who took the students, may have given them to the drug cartels.

Zedillo, who served as president of Mexico from 1994 to 2000, now teaches classes in political science and international relations at Yale.

“We are here to hold Yale University accountable for harboring a war criminal in our community,” said Foran, reading from the protest’s official press release.

For many in the crowd — Mexican nationals themselves or migrants from other Latin American nations — the recent events in Guerrero, as well as the 1997 Acteal massacre, are a sign of the violence that undocumented migrants to the U.S. try to escape by crossing the border.

“This shows the reality in Mexico,” said protestor Fatima Rojas, another New Haven resident.

The protestors, who drew parallels between the Acteal massacre perpetrated during Zedillo’s presidency and the violence in Mexico today, spoke out at a time of heavy criticism in Mexico for the country’s current president, Enrique Peña Nieto. Both Nieto and Zedillo align with the Institutional Revolutionary Party — a party that formerly dominated the Mexican political sphere — which some believe may contribute to the recent revival of interest in Zedillo’s case.

A few Yale alumni attended the rally, including Stephen Kobasa DIV ’72. Kobasa said that, although Yale is not the only institution to do so, he is disappointed by recent decisions that he said prioritize the University’s interests above that of the public.

“There’s no neutrality anymore — the University is identifying itself with this kind of institutionalized horror,” Kobasa said. “One must stand and say no.”

All of those who spoke at the rally highlighted the importance of undergraduate student involvement in fighting Zedillo’s presence at Yale.

In addition to his role as the director of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization, Zedillo is one of 11 former heads of state now serving as members of The Elders, an international human rights organization founded by Nelson Mandela.

Interested in getting more news about New Haven? Join our newsletter!