An auditorium’s worth of angry residents faced the committee.

It was March 6, and city lawmakers were on stage for the first public hearing on the mayor’s proposed budget for the 2014-’15 fiscal year. Over the course of two hours of testimony, an ultimatum emerged: if you raise our taxes, we will leave New Haven.

“I love this city. But I don’t think I’m going to be here next year to stand in front of you and have this conversation because I can’t live here anymore,” Gerald Kahn of St. Ronan Street told 10 alders from the finance committee who had gathered at East Rock’s Hooker School for the hearing.

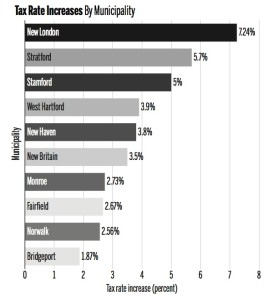

Another man said he had already picked up and left the city. He had moved to Milford, where he pays 30 percent less in property taxes than he would pay in New Haven. The contrast will be even starker if taxes go up by 3.8 percent this year, as Mayor Toni Harp has requested in the budget she submitted to the Board of Alders at the beginning of March.

“If we were an outlier — if our taxes were higher than every other urban place in our state — then I would say that we’re out of line for what it takes to run a city.”

Tax hikes are not new. Indeed, the current fiscal year’s budget included a bump in property taxes.

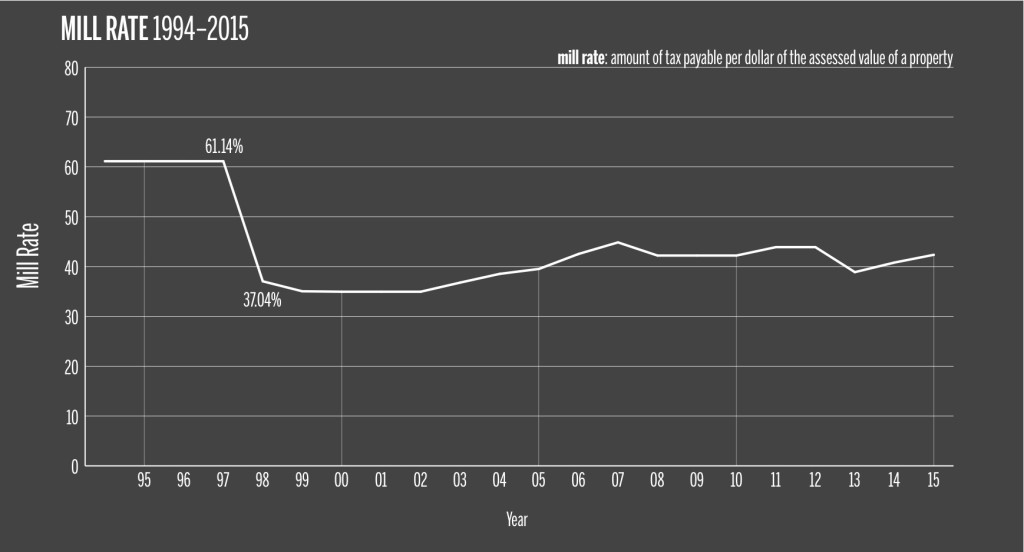

New, however, is New Haven’s mayor — the city’s chief executive whose job it is annually to weigh projected revenue with expected costs and then submit a financial plan to the Board for approval. Harp’s tax hike would increase the contribution from $40.80 to $42.36 for every $1,000 of property value.

Today is Toni Harp’s 100th day in office. She was sworn in January 1, two months after scoring a decisive general election victory to become the city’s 50th mayor.

Harp’s first 100 days have not been marked by grand pronouncements or evidence of a major reorientation in the wake of the 20-year tenure of John DeStefano Jr. The city wants stability more than it wants change, Harp said in an interview following her election last November.

During a conversation at the end of March in her second-floor City Hall office, Harp listed off a handful of actions that have defined her fledgling tenure as mayor, including spearheading a commercial activation program to help revive city neighborhoods, a central plank of her campaign platform last fall. Harp said she has made strides with the Board of Education in continuing to “retrofit our schools.” In recent days she has pledged to quell gun violence following the shooting death of 16-year-old Torrence Gamble Jr. last week.

But on the issue of the budget — now at the forefront of City Hall’s priorities — Harp said she is beholden to fiscal choices she did not make.

Her job is to “right the ship,” she said of the budget she had to submit after just two months in office. She said she feels constrained by difficulties from the current year’s budget, among them a $600,000 shortfall in the fund balance, which is the city’s savings account or “rainy day” fund.

DeStefano declined to be interviewed. Board of Alders President Jorge Perez, the second-most powerful elected official in the city, offered this faint promise following the second public hearing, held last week at Hill Regional Career High School: “This committee will do everything it can to either eliminate or substantially reduce the tax increase.” When pressed, he said it was too early to suggest potential offsets.

Residents asked the committee to scour the budget for waste before sending it along to the full Board of Alders for a vote. The new budget takes effect July 1.

Jim Duarte, the last to give public testimony, concluded by leading the audience in a chorus of “No!”

No to the tax increase, no to the mayor, no to her staff.

“Like the turning of the seasons, every spring we come back and the budget is passed no matter what we say,” Duarte said. “And over and over and over it goes.”

BUILDING TOWARD SUSTAINABILITY

Harp’s proposed budget for the 2014-’15 fiscal year is “structurally sound,” said Joe Clerkin, budget director since 2011 and a city staffer since 1988.

Structural soundness means no “gimmicks,” according to City Controller Daryl Jones, who oversees day-to-day expenditures. The city has not budgeted revenue from street sales or other one-shot deals; it has not borrowed money from future debt repayments down the road. Jones said the budget’s twin virtues are transparency and prudence.

It has not always been this way, Jones and Clerkin emphasized.

In 2011, the same year that Clerkin came on as budget director, his then-boss DeStefano laid off 82 city workers, including 16 police officers, in an attempt to close a $5.5 million budget deficit ending that fiscal year. The city’s fiscal outlook was grim; the 200 police officers marching through downtown streets to protest the layoffs served as concrete proof.

Clerkin said the city was “caught in the buzz saw of the national economy tanking.” Revenue narrowed, forcing the city to rely on one-time earnings, such as the sale of an asset, building permit fees or savings on labor concessions. Multiple years in a row, the city mistakenly budgeted millions of dollars in fees for building permits they expected Yale University to pull for its two new residential colleges.

When those funds vanished, the city’s finances took a hit, and city employees cleaned out their offices, said former controller Mike O’Neil.

The multimillion-dollar deficit that closed the fiscal year in 2013 drilled a hole in the rainy day fund, a $4.7-million negative fund balance that threatened to further weaken credit ratings. By the fall of 2013, three major agencies had downgraded the city’s bond rating, making it more expensive to borrow money.

DeStefano’s budget office acted quickly to prevent ratings from plummeting. The strategy to save now and pay later seemed the lesser of two evils, Clerkin said. The $4.7-million deficit was reduced to roughly $600,000 by a borrowing scheme that took more than $4 million out of future debt repayments and put it instead toward replenishing the depleted fund balance. The rainy day fund is still in the red, but less so.

A small portion of the spending increase in Harp’s proposed $510.8 budget would go toward putting more money away for rainy days, “in case another Hurricane Sandy strikes,” Clerkin said, completing the metaphor.

The budget includes $2 million for a “Five-Year Financial Plan,” divvied up among the fund balance, medical payments and a new “pay as you go” capital projects fund that would allow the city to pay for infrastructure improvements with cash on hand rather than borrowed money.

The budget includes $2 million for a “Five-Year Financial Plan,” divvied up among the fund balance, medical payments and a new “pay as you go” capital projects fund that would allow the city to pay for infrastructure improvements with cash on hand rather than borrowed money.

O’Neil said he sketched out the details of the financial plan “on the back of an envelope” over the course of a few hours in early January before Jones took over as controller. Had DeStefano pitched the idea before the transition, O’Neil said, he would have been slammed for increasing spending with one foot already out the door.

PAST COSTS, FUTURE OBLIGATIONS

Harp is asking to spend $13 million more next fiscal year than the city doled out this year. Most of that increase comes in the form of “legacy costs,” expenses incurred before she took office.

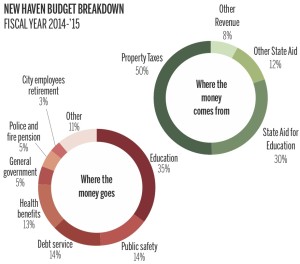

Pension payments and medical benefits each went up nearly $2 million over the current year’s budget, while debt service — annual loan repayments — went up twice as fast. Altogether, these fixed costs account for over 35 percent of city spending.

Pensions loom large among the city’s financial challenges. If every city employee retired tomorrow, the city would be $500 million short in savings for their retirement, Jones said.

The city has made small modifications to ease its financial obligations. New hires in executive management now enter with defined contribution plans rather than defined benefit, which means their retirement stipend is not based on a set formula but rather dependent on investment returns.

Under a new contract pending approval by the Board of Alders, firefighters will have to kick more money into their own defined benefit plan. The contract took a whopping three years to negotiate.

Of the city’s 14 other municipal bargaining units, a handful have contracts that expire in 2015. Whereas DeStefano had accumulated history with each of the unions, Clerkin said, Harp has a fresh start. With that comes an opportunity to engage the unions away from the negotiating table.

Of the city’s 14 other municipal bargaining units, a handful have contracts that expire in 2015. Whereas DeStefano had accumulated history with each of the unions, Clerkin said, Harp has a fresh start. With that comes an opportunity to engage the unions away from the negotiating table.

Mendi Blue, Harp’s acting labor relations director, said the city will seek incremental change rather than a sweeping alteration to the structure of benefits. She said each union lays enormous claim to what is ultimately a “finite” pot of money.

But union stewards said they were unconvinced by the city’s claims of financial distress.

“I’ve been with the city 25 years. They always claim they’re broke,” said Dominic Magliochetti, former president of Local 71, which represents blue-collar city workers.

Standing up to public sector unions is a political death wish, said Yale School of Management Professor Doug Rae, who took a break from teaching for a stint as chief administrative officer in the early 1990s under former Mayor John Daniels.

When industry fled the city in the 70s and 80s, Rae said, the union movement transferred its base of operation to government and to the city’s largest nonprofit, Yale.

“DeStefano fought them a little harder than anyone had before him, but the benefits and pension requirements of those unions are the central issue going forward,” Rae said. “And no mayor who wishes to be reelected is likely to lay a hand on them.”

When asked about her strategy, Harp sidestepped the issue of the obligations themselves, saying she intends to make sure the funds are managed well on the stock market.

Paying down pension obligations must form part of the city’s financial plan, the initial steps of which Harp’s budget lays out, Jones said.

“What the city needs now is to create policies that will govern its finances — so every year, you set a number that your fund balance has to reach or a number that pension contributions have to reach,” Jones said. “I couldn’t do that in two months. But it’s one of my eventual goals.”

Another one of his goals? No tax hike next year.

BRINGING HOME THE BACON

Today, property taxes account for 50 percent of the city’s revenue, roughly $250 million. The preponderance of nontaxable land, owned by the state or tax-exempt colleges and hospitals, means homeowners and businesses must pick up the tab.

Connecticut’s Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program, designed to compensate municipalities for nontaxable property, has fallen drastically short of meeting expected reimbursement levels. In 2014, New Haven — where roughly 47 percent of property is tax-exempt — is slated to receive $43.6 million in PILOT, well under half the amount that the formula, 77 percent for colleges and hospitals and 45 percent for state property, is designed to provide.

State aid and property taxes are just about the only two revenue streams these cities have at their disposal. Permitting fees, fines and other revenue streams are virtually negligible for New Haven, Clerkin said.

Cincinatti, by contrast, has a payroll tax, said John Glascock, director of the Center of Real Estate and Urban Economic Studies at the University of Connecticut School of Business. Cities elsewhere levy income taxes and sales taxes, whereas Connecticut municipalities have only the property tax.

When asked to defend the tax hike, Harp, Clerkin and Jones — the city’s three most important financial officers — all began with personal appeals, saying they empathized because they themselves are taxpayers. Harp and Jones pay property taxes in New Haven, Clerkin in Cheshire.

“I don’t know what you say, honestly,” Clerkin said. “This is what we need to do to provide these core services that the mayor and the Board of Alders feel are important for the residents of the city.”

If New Haven were allowed to tax all of its land, it could maintain one of the lowest mill rates in the state, Harp said wistfully. Still, she said, New Haven’s rate is lower than the rate in comparable municipalities, including Hartford, Bridgeport, Waterbury and New Britain.

“If we were an outlier — if our taxes were higher than every other urban place in our state — then I would say that we’re out of line for what it takes to run a city,” Harp said.

Waterbury Mayor Neil O’Leary proposed a 3.5 percent tax increase for the 2014-’15 fiscal year, largely as a means of coping with soaring healthcare costs, according to Kevin DelGobbo, senior advisor to the mayor. Bridgeport Mayor Bill Finch proposed a 1.87 percent increase. Both increases are slimmer than Harp’s proposed 3.8 percent hike, but they operate on steeper existing tax rates. Taxpayers in New Haven will still pay comparably less, Harp noted.

Mike Stratton, alder for Prospect Hill and Newhallville and among Harp’s most strident critics, blasted her economic rationale. Comparing New Haven’s mill rate to the rate in Hartford and Bridgeport is to suggest the city should measure itself against places that, financially, resemble “devastated third-world countries,” he said.

In the wake of Harp’s budget announcement, Stratton lambasted the proposal — and the early days of the new administration, calling Harp a “catastrophe.”

Stratton said his disagreement with Harp’s budget arises from different philosophies about the potential of cities like New Haven. In his view, taxes should be cut, creating incentives for businesses and families to move into New Haven, and city bureaucracy should absorb the cost.

“She’s been raised in a political culture where the city is considered a welfare organization, not an autonomous municipality,” Stratton said.

In order to make further spending reductions, Harp responded, residents would have to expect vastly less of their government. She pointed to the anticipation of swift snow removal following the winter’s bout of storms as evidence that people want high-performing services, which requires spending.

All the fat has been trimmed from the city, Harp said bluntly: “We’re almost at a place — we’re almost at the basic cost of having government as we know it.”

City departments cannot be downsized, she said. The Parks Department has already lost 50 percent of its staff over the last 15 years. The Public Works Department is down by 30 percent. To suggest further cuts is to ask whether these departments should continue to exist at all, Harp said.

Even so, Harp did demand cuts of her department heads: an across-the-board two percent reduction in spending. That request was communicated in a City Hall memo that reached the desks of department heads just a few weeks into the new administration. It was followed by one major meeting with all department heads where the mayor explained the rationale for the cuts and laid out her goals, recalled Economic Development Administrator Matt Nemerson SOM ’81.

“She was like a commander-in-chief — with every line item committed to memory,” Nemerson said.

Cuts to his department meant he was unable to hire a junior electrical inspector, as his building staff had requested, Nemerson said. He felt himself unable to “bring back the bacon.”

Doug Hausladen ’04, head of the Transportation, Traffic and Parking Department, said spending cuts defined “how many linear feet of paint” he had at his disposal for crosswalks.

SEARCHING FOR THE SWEET SPOT

Richard Pomp, professor of tax law and policy at the University of Connecticut School of Law, said debates over the appropriate level of taxation bring to mind the Laffer curve, a plot of the tax rate versus expected revenue that Arthur Laffer, an economic advisor to President Ronald Reagan, supposedly drew on a napkin during a dinner meeting with officials in President Gerald Ford’s administration.

“In theory there is a sweet spot, and after a certain point raising taxes produces less revenue because of the negative effects,” Pomp said. “The only problem is that nobody ever knows where the sweet spot is.”

Rae said taxes are reaching a “breaking point” — a level at which people start selling their homes, the values depreciate and there comes a “death spiral.” Of course, he added, “Yale can’t permit that.”

In response, Yale President Peter Salovey said he does not envision a “death spiral” striking New Haven. He professed faith in the city and the state, adding that the city has improved dramatically with the University’s help.

Stratton and Henry Fernandez LAW ’94, a former city economic development administrator and one of Harp’s opponents in the Democratic primary last fall, said the mayor is partially responsible for the Elm City’s budget woes as a former state senator representing New Haven. For 11 years, Harp chaired the appropriations committee that decides how much aid the state budget includes for cities.

Municipal aid already accounts for close to 25 percent of the state’s budget, according to State Budget Director Ben Barnes. Contrary to popular belief, Barnes said, the allotments have not diminished but rather increased since 2000. Still, they have not kept pace with the expansion of nontaxable property.

Harp bristled at the suggestion that she had let her district down. She said she fought for municipal aid despite widespread cuts following the recession.

“I wish at the time our economy had been better and we could have done more, “Harp said. “It’s better today. Maybe I should have stayed and we could have done more.”

If the state finds a surplus in its budget, Harp said, it should return that money to cities — an argument that might resonate especially well with Gov. Dannel Malloy in during an election year, she added.

NECESSARY AND UNTENABLE

Visions are set in the first 100 days. It is typically a time for major policy requests when a leader’s power and influence are at their zenith. The highest-profile request Harp has made of her legislative counterpart has been for seven new City Hall positions — six in the mayor’s office, including a bilingual receptionist and a grant-writing office.

Before a March vote approving three of the requested positions, President Perez — who, along with a majority of his colleagues on the Board, endorsed Harp last fall — said the new mayor has to be given room to lead the city, which means making changes to the budget.

“You have a new mayor asking to put her fingerprints on the budget,” Perez said. “At some point she’s going to be up for reelection and going to have to face the voters and they will say, ‘you promised this and you promised that, and you didn’t do it.’”

One promise Harp has already abandoned is delivering a results-based budget, said fiscal watchdog Gary Doyens. Her fiscal plan is no different from the ones DeStefano pitched, Doyens said at last week’s budget hearing — the ones that have brought property taxes to a breaking point.

This is not change, Doyens said, “this is moving the chairs around on the Titanic.”

Department heads submitted preliminary budgets last December. This year, they are largely executing their predecessors’ financial plans. By next year, they said, they will have had more time to reorient finances to reflect different policy commitments.

The same goes for Harp, except she has her predecessor’s record 20 years in office to unwind, tweak or advance — and first she has to choose which of those three paths to pursue.

Rather than dwelling on the first 100 days, Harp took a long view; the city’s problems have solutions, she said, and they require sustained intellectual commitment by city officials, “some of the greatest thinkers in the world.”

Rae, who returned to Yale after 18 months in Daniels’ troubled administration, said the new mayor should be given time to lead.

“You have to be mayor for a while to actually be mayor, to be held accountable,” Rae said. “Most of the conditions affecting the city most dramatically are knock-ons from a 20-year administration that came before.”

One of those conditions is the burden of raising property taxes, Rae concluded — a decision both “necessary and untenable.”

Interested in getting more news about New Haven? Join our newsletter!