Max de La Bruyère, a senior reporter for the News, spent six weeks this fall with the members of the Yale men’s cross country team. This is part one of a two-part series. (Read part two.)

Ryan Laemel ’14 was fading. Just over 2.5 miles into the sub-varsity race at the New England Championships, the Yale junior had fallen five meters behind the lead pack of runners. In a distance race like these eight kilometers through a park in Westfield, Mass., gaps are dangerous. Once you have let one form, you have broken contact with the runners ahead of you. You can start slowly to fade away.

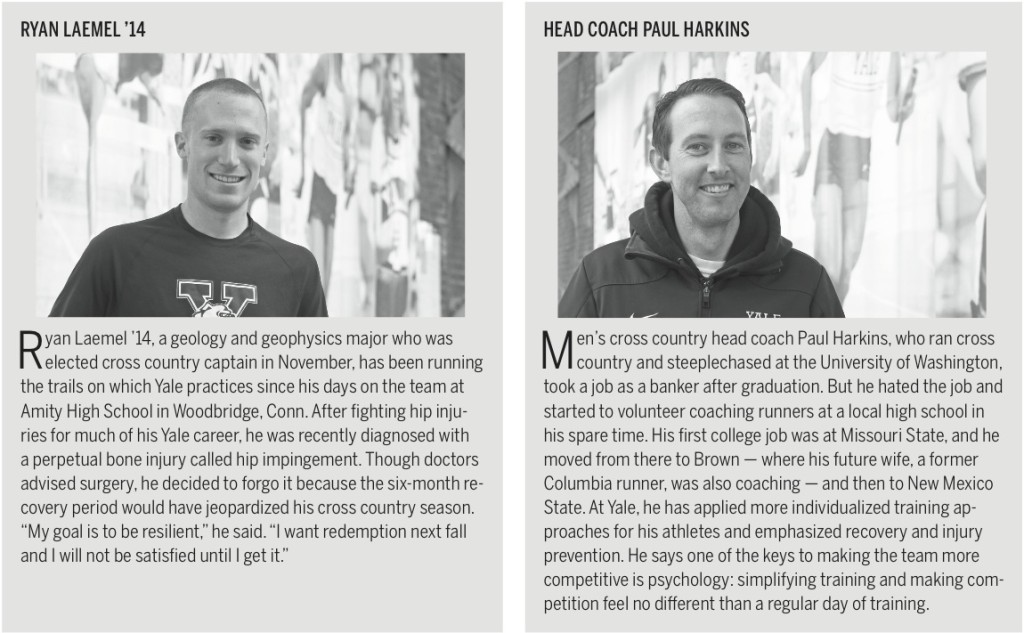

Yale men’s cross country coach Paul Harkins, who had sprinted from one vantage point near the two-mile marker to this turn into the woods, saw Laemel sinking slowly behind the leaders. Another one of Yale’s runners, Ahmad Aljobeh ’16, was leading the three-man pack at the front. Harkins gave a shout of encouragement as Aljobeh passed, but he saved his voice for Laemel.

“Get with them!” he screamed. “You’re as fast as these guys. Get with them! Get with them!”

Laemel sped up slightly, inching a stride or two closer to the leaders. Then he made his turn into the woods and out of sight, and the main pack thundered by Harkins’s spot along the course. The coach looked for his two other runners in the race and shouted encouragement as they passed. Then they too were gone, and he started walking toward Yale’s tent, where the runners who would compete in the varsity race were starting to warm up. Laemel and Aljobeh would not be out of the woods for another 10 minutes. All Harkins could do was wait.

Halfway through the fall and with three weeks to go until the Ivy League championships, 2012 was a hopeful season for the Yale cross country team. The year before, Harkins’ first at Yale after four as an assistant at New Mexico State, the Elis finished a distant sixth of eight teams at Ivy League Heptagonal Championships. That was a slight improvement over the previous three seasons, when they consistently finished seventh. “People are asking, ‘Is this the year Yale finally gets its head out of its a**?’” team captain Kevin Lunn ’13 told me as we drove from New Haven to Massachusetts to watch the New England Championships. He believed it was.

Though the team lost its traditional dual meet against Harvard on Sept. 14, it made up for that with its performance at the Paul Short Invitational in Pennsylvania two weeks later. A year after finishing 19th in the 37-team field, Yale ran its way to seventh place. Going into the race, the team was confident in its abilities compared to the year before. But the extent of their improvement at Paul Short, a week before New Englands, was shocking.

STUDENTS AND ATHLETES

Distance running is an unforgiving sport. The only number that matters is seconds on a clock. There is nothing else to hide behind. The runner cannot pad his statistics against an inferior opponent or shrug off a poor performance due to a rival’s impressive play. There is only the cold, objective truth of minutes and seconds. He is defined by his times. Statistics only approximate a football or basketball player’s performance, but a 4:05 miler is a 4:05 miler. Period. When, on one perfect day, he runs a 4:02 mile, his place in the world will have shifted. Until then, he knows he is greater than every 4:06 miler in the world, and less than every 4:04 miler.

Those times take on even more meaning in college cross-country. Of the six races in which Yale’s varsity team competed in 2012, only two truly counted: Ivy League Heptagonal Championships, or Heps, which determined the pecking order within the Ancient Eight, and the NCAA Regional Championships, the team’s chance to qualify for NCAA Nationals and a spot among the elite of the college running world. Races like Paul Short and New England Championships are nothing more than opportunities for the team to gauge its progress and readiness for competition relative to its rivals. Impressive performances at those meets are exciting, but everything is decided at Heps and Regionals.

Neither meet has treated Yale well in recent years, and the team has spent the better part of a decade mired in the bottom half of finishers at Heps. Its struggles can be explained a variety of ways. The number of athletic recruits at Yale has declined steadily over the past 20 years, and that change has affected varsity rosters. Yale had 25 men on its cross-country roster this year; Harvard had 35. Because of recruiting holes, the Elis depend more heavily on walk-ons than most comparable programs.

Perhaps most importantly, there is a self-fulfilling nature to college athletic programs. Teams that win lure the most talented recruits. Yale has not done much winning recently.

But the team keeps running. They do so on a campus where a column appears in this newspaper on an almost annual basis calling for an end to recruiting, and where student attendance at the vast majority of sporting events is all but nonexistent. Many Yalies do not hesitate to declare varsity athletes less intelligent than their nonrecruited classmates. For fear of the assumptions their professors would make, many athletes avoid wearing team apparel to class.

I wanted to understand what motivates the members of one of Yale’s 33 varsity teams to commit themselves to the elusive pursuit of a kind of success few of their classmates understand, let alone value. So I approached Kevin Lunn ’13, the cross-country captain, in early September and asked if he would be willing to let me unofficially walk on to the team. I would practice, eat and travel with the Elis, doing everything short of competing.

Lunn agreed, and Harkins, the head coach, did too. Yale’s NCAA compliance director found no regulations that would ban my participation, and I was cleared to run. On Monday, Oct. 1, I met Lunn and his teammates for the bus ride from campus to Yale’s athletic fields.

Mondays are an easy day of training: seven to 11 miles, depending on the individual athlete’s conditioning schedule. Then the team convenes at the track for sprints and abdominal work, followed by a trip to a grungy basement weight room in Smilow Field Center. The bus for practice left at 2:45 p.m.; we were back for dinner four hours later.

THE CAULDRON

The pace at this Monday practice six days before New Englands was easy enough I could keep up, and I ran alongside Laemel for the second half of my seven miles. Due to injury trouble the year before, he was running only 60 or so miles a week, in addition to bicycling and swimming. Less injury-prone members of the team will run up to 80 miles in a given week during the season. Over the summer, some run more than 100.

After pre-run stretching at the Yale track, we took off down Derby Avenue, past a cemetery, two used car dealerships, a liquor store and a Dunkin’ Donuts, breathing exhaust fumes and watching out for stoplights. Then, with a quick turn onto a hidden trailhead, we entered the woods of the Maltby Trails and the sound of cars started to fade. Voices picked up; on long runs like this, conversation helps the athletes keep going. A training run is almost a social experience. The coach doesn’t run with the team, so for this hour in the wooded trails off campus, it was just us, moving at a steady but not backbreaking pace.

“The way conversation works on the trail is like a moving cafe,” said Duncan Tomlin ’16, a walk-on unsure about whether he wanted to stick with varsity athletics through the winter and spring. “Guys will speed up to join one conversation, then slow down as it changes to talk with other guys. You’re always having to find new topics of conversation, different kinds than you would find for non-running conversations.”

After about 25 minutes along the trails, we ran into Laemel and headed back with him toward the track. Conversation turned almost immediately to racing.

Laemel had been one of the 10 runners Yale sent to the starting line in its successful Paul Short appearance three days before this practice. In a college cross-country meet, only the top five finishers count toward the team’s score. The overall place of the sixth and seventh finishers on a team are also important, as they are counted in the case of a tie, and can bump other teams’ bottom runners down the leaderboard. This early in the season, Harkins was not sure who his top five would be. He received some pleasant surprises: Matt Nussbaum ’15, a sophomore, had a breakout performance and finished first among Yale’s competitors. Kevin Dooney ’16, a freshman from Ireland whose brother had graduated as one of the team’s top runners the year before, finished fourth on the team. Laemel, a junior coming off a solid outdoor track season the spring before, finished dead last on the Yale team and tied for 206th in a 332-man field.

On the bus home from Paul Short, as the team celebrated the day’s success, he sat quietly by himself looking out the window, wondering what went wrong. Lunn came over, and Laemel asked for advice.

“There’s a key difference between disappointment and despair after a race,” Lunn said. “Being disappointed means asking yourself, ‘What could I have done better, what areas could I have improved on?’ Despair means giving up. Take some time to be disappointed now. And then figure things out in practice.”

I asked Laemel what separates a good race from a bad one. “It’s all psychological,” he said.

In Laemel’s telling, there’s something like a cauldron in the middle of your body, somewhere in between your hips and just below your belly button. In the second mile or so of a race, that cauldron starts to bubble and ooze over, and to hurt, he said, “Like hell.” The rest of the race depends on the runner’s ability to ignore the pain from that cauldron. At Paul Short, Laemel had let the cauldron get to him. He would not allow it to happen again.

And yet there he was just over a week later at New Englands, fading behind the leaders in the sub-varsity race as he turned into the woods.

CONTROL THE HURT

New England Championships don’t matter. The sub-varsity race matters even less. The race’s lofty name stopped meaning anything years ago; it’s one of the bigger meets in the region each year, but it attracts mostly second-tier Division I programs and Division III liberal arts colleges. Yale had not even brought its top seven runners, nor had Ivy League rival Dartmouth, which was favored to win the upcoming varsity race. Those top runners would be flying to Wisconsin the next week for what was likely to be the most competitive meet of their season. Winning New Englands was, at most, an afterthought. And winning the New Englands sub-varsity race was not even an afterthought — it was impossible. Yale was running four men in the race, one short of the five necessary to contest the team title. Harkins was having those four run because he didn’t need to win. He just wanted them to race. He wanted Laemel, for one, to exorcise the demons of Paul Short.

So as Laemel rounded the turn into the woods behind the leaders, Harkins scowled briefly before jogging back to Yale’s tent, where the men who would be running varsity were warming up for their race.

Ten minutes after Laemel and Aljobeh entered the woods, Jacob Sandry ’15, a sophmore on the team from Minnesota who had wandered off in the general direction of the racecourse, came sprinting over.

“Ryan’s killing it, guys!” he shouted. “He’s all alone.”

Warm-ups were forgotten, and Sandry and his teammates sprinted over to the course. Laemel’s bright, closely-cropped red hair soon appeared around a turn, 25 meters ahead of his closest competitor. His teammates shouted encouragement as he passed, then waited for Aljobeh, who had dropped back into fourth place in the woods. Then it was time to jog back and stretch. Their race was approaching, and there was no time to see the finish. It was a foregone conclusion anyway. This might not have been a high-caliber race, but Laemel ignored the boiling cauldron and managed the gap. He was back. Harkins was ecstatic.

“With racing, everybody’s going to feel like s*** at some point — even the winner,” Harkins said, bouncing on the balls of his feet about 20 minutes after the sub-varsity finish as he waited for the varsity race to start. “Ask Laemel. I’m sure he felt like s*** today. But you just have to be able to get through when everybody’s hurting, you have to realize that everybody’s hurting. It’s about who can control it the best, who can control the hurt, who can withstand the hurt. They’re the ones who are going to come out on top.

“Laemel was right on the edge, I felt like, through two miles. He was controlling it, but he was like, ‘Do I really stick with these guys, do I trust it, do I go with it?’ Then I just yelled at him to get up there, he responded, got up there, then all of a sudden he comes out of the woods…”

Harkins trailed off. The Dartmouth coach was approaching, and the two men started talking numbers. Both were running their B teams today, as their top runners trained in preparation for the big Wisconsin meet the next week. Harkins didn’t care who the men running today were. His team finished 17th here the year before. He thought they could win this year and show their competitors that their roster was deep enough that they could not be counted out.

“There is nothing to get in your way,” he had told his runners in a huddle before the varsity start. “Run tough through the middle. No gaps. We’re going to f****** win this thing.”

Behind a strong finish from Sandry, Yale went on to finish third in the varsity race. Especially on the heels of the Paul Short success, that was a huge victory. As the team huddled following the finish, Harkins was bouncing again.

“You’ve got to test the limits now and then, and you went after it,” he said. “Keep running, run with a little more confidence, and we’re going to beat some good f****** teams.”