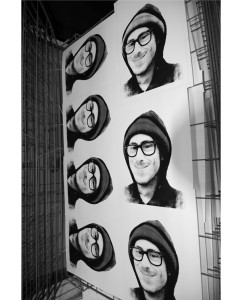

Some of you might have noticed the appearance of posters around New Haven bearing the face of a grinning young man wearing a beanie and a hoodie. His portrait is nearly life-size and hangs at eye-level. Maybe you smiled back at him.

These 100 posters commemorate Mitchell Dubey, who was murdered in his New Haven apartment two years ago when a panicked robber shot him.

This story might shock people familiar with the posters, which do not directly allude to their subject’s tragic history. Only a caption, “Mitch,” identifies the musician and bicycle enthusiast.

This story might shock people familiar with the posters, which do not directly allude to their subject’s tragic history. Only a caption, “Mitch,” identifies the musician and bicycle enthusiast.

Scrawled next to the caption is a small signature, “J.B. Weekes.” Jonathan Weekes is a graphic designer and a friend who made these posters to remember and celebrate Mitch’s life. Jonathan met Mitch when they worked together at The Devil’s Gear Bike Shop, where the pair repaired bicycles and swapped musical interests.

Jonathan made the posters last year, too, and plans to do so annually. He says, “It has become both my way of coping with and expressing the senselessness and tragedy of his loss.”

Jonathan chose to exclude text because “Mitch’s image was enough to allow it to stand on its own” — his magnetic, charismatic presence alone inspires people to investigate. “You want to get to know him,” Jonathan explained, “That is exactly the way he was in life.”

The posters’ paper stock is vulnerable to New Haven’s weather, and Jonathan notes that this fragility represents the preciousness of life — a gift that is never guaranteed. “People see [the posters] one day, and then they are gone the next. Once they are gone, all that remains is the memory.”

The transience of the prints contrasts with the indelible sorrow of Mitch’s story, and it brings into question how time affects reactions to tragedy. Often, incidents like Mitch’s flood local news until the community reaches some degree of justice. In Mitch’s case, police arrested the robber responsible for his murder.

Sometimes politicians and activists use the hype surrounding tragedies to promote their own causes. We recently saw how inevitable political commentary proved with the Sandy Hook Elementary School tragedy, where other innocents died in gun violence. Parties from either side of the firearms debate rose up around the mourners and preached their ideologies as solutions. After attempts to reach inherently inadequate resolutions, however, interest calms, and people move on.

Is this how should we respond to incredible misfortunes? No. Though difficult to avoid, it is important that we do not forget tragedies because they passed. Though we are averse to facing the suffering that comes along with reflection, we must allow ourselves to remember the wonderful people we lose. It is as necessary to experience this sadness as it is to heal and embrace life. Resisting the use of others’ tragedies to further political agendas is also important, regardless of however well-intentioned or relevant those agendas might be. To practice otherwise disrespects the real, personal losses with which communities are trying to cope. Not unless a mourner calls for change of law does this response acknowledge the sacrosanct grieving of the beloved.

Art provides perhaps the most appropriate and palliative means to cope with human loss. It is cathartic to the creator and viewer, and it honors its subjects. The power of art to organize otherwise senseless experiences in constructed frames truly influences people, who reach their own conclusions and shape their communities accordingly.

Jonathan Weekes’ perennial prints of Mitch provide an admirable model for how we might remember tragedy. Hopefully the incredible life he calls to our attention will affect the way we live. We should aim to share the “positivity, tolerance and pure love of life” that Mitch exuded.

I encourage you to take some time to walk down Grove Street and look for Mitch if you haven’t already seen him. The weather is beautiful, and life is too brief not to enjoy it. In Mitch’s own words, “Follow through on some strange plan. Forget to follow through on something possibly important. Ride your bike. Do something.”

“Do something, anything,” he said, “I beg you.”

Alexis Steele is a senior in Trumbull College. Contact her at alexis.steele@yale.edu .