My grandfather is the most fearless person I’ve ever met.

I don’t mean that he’s fearless in the inciting-global-change way of the Malala Yousafzais of the world. I mean fearless in the literal sense. He lacks any and all fear.

Case in point: the time he traveled through a civil war zone for a vacation.

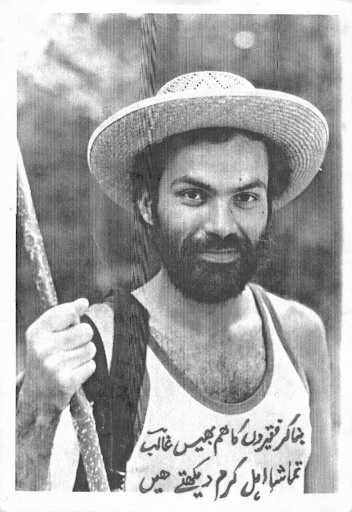

It was 1993, and my grandfather, Sohail Rabbani, whom I call Nana, was taking a break from his obligations in Birmingham, Alabama and visiting family in Karachi. Ann, his American friend whom he had met while backpacking through Scotland — a story for another day — had ventured across the Atlantic to explore Pakistan. Coincidentally, so had a cousin of Nana’s half-sister’s cousin-in-law — Pakistani family trees are complicated, y’all — named Mehmooda. Mehmooda had grown up in England and was on an Eat, Pray, Love “reconnecting with my roots” trip in Pakistan. The three of them met up and quickly became a dynamic trio, exploring beaches together in Karachi. But the sun and sand bored them and they grew restless, itching for another, greater adventure.

Nana resolved on going to Chitral, a city in the extreme northwest corner of Pakistan, right next to the border with Afghanistan. It was perfect, he reasoned: they could see the towering mountains and clear lakes, affectionately dubbed the “Swiss Alps of Pakistan,” and he could act as a guide and protector for his foreign female companions, who couldn’t go by themselves.

They formulated a plan: they would drive to Peshawar, a major city in the north of Pakistan, and take a flight to Chitral from there. They thought it was perfect, foolproof even.

Yet, as often happens, nothing went according to plan. No sooner had they arrived in Peshawar than they learned that every flight had been cancelled due to the inclement weather in the mountains. Never one to give up without a fight, Nana began searching for a route through the treacherous mountains. No dice. Not only would it have been incredibly challenging even without the weather, but all of the roads were blocked. There was no path to Chitral from anywhere in Pakistan that they could feasibly get to.

Now, a normal person at this point would have cut his losses, said “sayonara” to his plans and booked it back to Karachi to soak up the sun. But not Sohail Rabbani, the most fearless man I know. As often accompanies fearlessness, he is also, and I say this with so much love, the most cuckoo person I know.

Hell-bent on going to Chitral, he decided to call up and ask the advice of an old teacher of his who lived in Chitral: Major Geoffrey Langlands. Langlands, who passed away in 2019, was a retired British major who resided in Pakistan long after colonial rule ended in 1947 and dedicated his life to teaching Pakistani schoolchildren. He was a beloved, valued member of the community, so much so that when he heard Nana’s plight, he put him in touch with a contact who could get him to Chitral. The only catch? They would have to detour through Afghanistan, while it was in the middle of the Afghan Civil War, in a smuggler’s caravan.

Naturally, he said yes. Do you see where the cuckoo of it all comes in now?

He made the arrangements, and by 4 a.m. the next morning, Nana, Ann and Mehmooda were in a van on their way. The girls, who were bundled up and had most of their faces covered, were sitting in the front with the driver, while Nana sat in the back with 11 other people, mostly smugglers and refugees.

Thus, they began their 18-hour journey. Nana, a social butterfly by nature, slowly broke through the silence and got to talking with the people in the van. They asked him questions about medicine, history and his life in America. He learned about their hardships and joys, their troubles and triumphs.

Their hours-long conversation was cut short by the Mujahideen, an Afghan militant group that represented one side in the civil war. The van was on a thin, barely two-lane mountain road when the military truck drove up to them from the opposite direction. On their left lay a ravine with no guardrails and the promise of a quick death if they were to fall, and on their right, the threat of military capture. Everyone caught their breath, barely daring to move as the van slowly rolled past the truck, mere inches between the vehicles. When the military truck was in the distance and they were home free, everyone let out a collective sigh of relief. Everyone, that is, except Nana, who had never been worried about the imminent threat of capture in the first place.

Aside from the appearance of another Mujahideen truck, the next few hours passed without any issues. Then, they stumbled upon the Kunar River. The river itself was not so bad: knee-height water, only about 50 feet across. Only, there was no bridge. Nana and all of the backseat passengers exited while only the driver and the women carefully navigated through the river in the van, whispering prayers that the rocks wouldn’t damage the tires. Nana and the others had to trudge through the river, shivering from the glacial water and hoping their thick clothes would dry out in time for their arrival.

The van’s dip in the river wasn’t enough to negate the blistering heat of a summer sun, and they were forced to stop and air out the van only a few hours later. While the passengers chatted, Nana spotted the driver pacing restlessly and muttering to himself while glancing at the sun, which was beginning its descent. Abruptly, he yelled at everyone to get back in the van because “safety is not guaranteed after sunset.” The driver put the pedal to the metal, and they crossed back into northern Pakistan just as the sun disappeared from the horizon.

Nana and his companions spent many days in Chitral, meeting Major Langland for tea and exploring the three major valleys in the area. “The scenery was so beautiful — meadows and crystal clear lakes everywhere,” he told me. I, still gobsmacked after hearing the story, had nothing to say. I always knew he was adventurous, but this set even my heart racing, and I wasn’t even there. I asked him if he was scared. As nonchalant as ever, he responded in the smooth tone I know is his patented grandfather voice, “There’s no sense in being afraid of things you can’t control. You have to do the things you want to do.” Still dumbfounded, I responded, asking what possessed him to travel through a civil war for something as trivial as a vacation.

He smiled, shrugged and uttered the most simple, stupid, genius, cuckoo-crazy response possible: “Why not?”