Illustration by Thisbe Wu

This piece received second place in the nonfiction category of the 2025 Wallace Prize.

You are a child in Lima, Peru, and like any child, your attention is drawn to peculiar sounds. One of them is a word, “Pentagonito,” and you attend to it not just because it sounds funny but because you’ve heard it repeatedly—mom, dad, grandma, and everyone you know pronounces its rhythmic five-syllable sound. You don’t know exactly what it is, but you know it’s important—part of the yet inaccessible world of adulthood—and so, perhaps unintendedly, you decide to store it in your memory.

One Saturday morning, a few years later, when you are perhaps eight years old or seven or maybe even only six, your mother wakes you early enough for you to hear the mourning doves: we have to go; your father is running a marathon, and we must cheer him at the finish line. You hear that word again, “Pentagonito,” and you remember it. You understand now, without hesitation, that it refers to a place—El Pentagonito is our destination.

And so, invaded by curiosity and love, perhaps unaware of the distinction between the two, you hop into the backseat of the car. Through the car window, you observe the familiar streets and houses slowly turn into something yet unknown. Suddenly, you find yourself under the shadows cast by an endless landscape of trees. You notice all the different sizes and shades of green, all the species you cannot yet name—eucalyptus, ficus, guayabo—and when you step out of the car, you witness something unlike anything you’ve seen. The immensity of the park, which you can see extending towards the horizon, has been taken over by a sea of people gathering around what seems to be a running course. Many of them cheer and jump in excitement when moving bodies approach the finish line, and so when you realize your father is one of those bodies, you also cheer and jump and roar under the sun. Invaded by joy, you think to yourself: this is a nice place; this is where people come to run.

In the years that follow, already familiar with this landscape of trees and river of runners, through the car window on your way to school, new sounds and shapes refine your impression of El Pentagonito. You start noticing bikes, scooters, skateboards, and neighbors enjoying morning walks. You see a playground, an activities center—which plays the role of a pilates club, a dance club, and a hub for martial arts—and an outdoor gym. You see a pond with a small bridge crossing through it, the perfect place for newlyweds and quinceañeras to encapsulate their memories with a photograph. There is a different couple and a different quinceañera every time; the photographers, however, are often the same.

Some days, you see your father running on your way to school. Neither you, nor him, nor your sister, nor your mother care about how much attention you’re drawing from other runners as you wave at him and scream “Papááá Papááá” in that high-pitched childish voice. Shame is not yet a thing.

One Sunday, your family decides to spend the day at El Pentagonito— “We’re going to take rollerblading classes!”—and you finally get to walk around the place. The landscape of trees, the scent of eucalyptus, the playground, the pond, and the newlyweds—they’re all still there. There is, however, something new. Something you haven’t noticed before but had been there all along, in the background of your field of perception, yet at the core of the place.

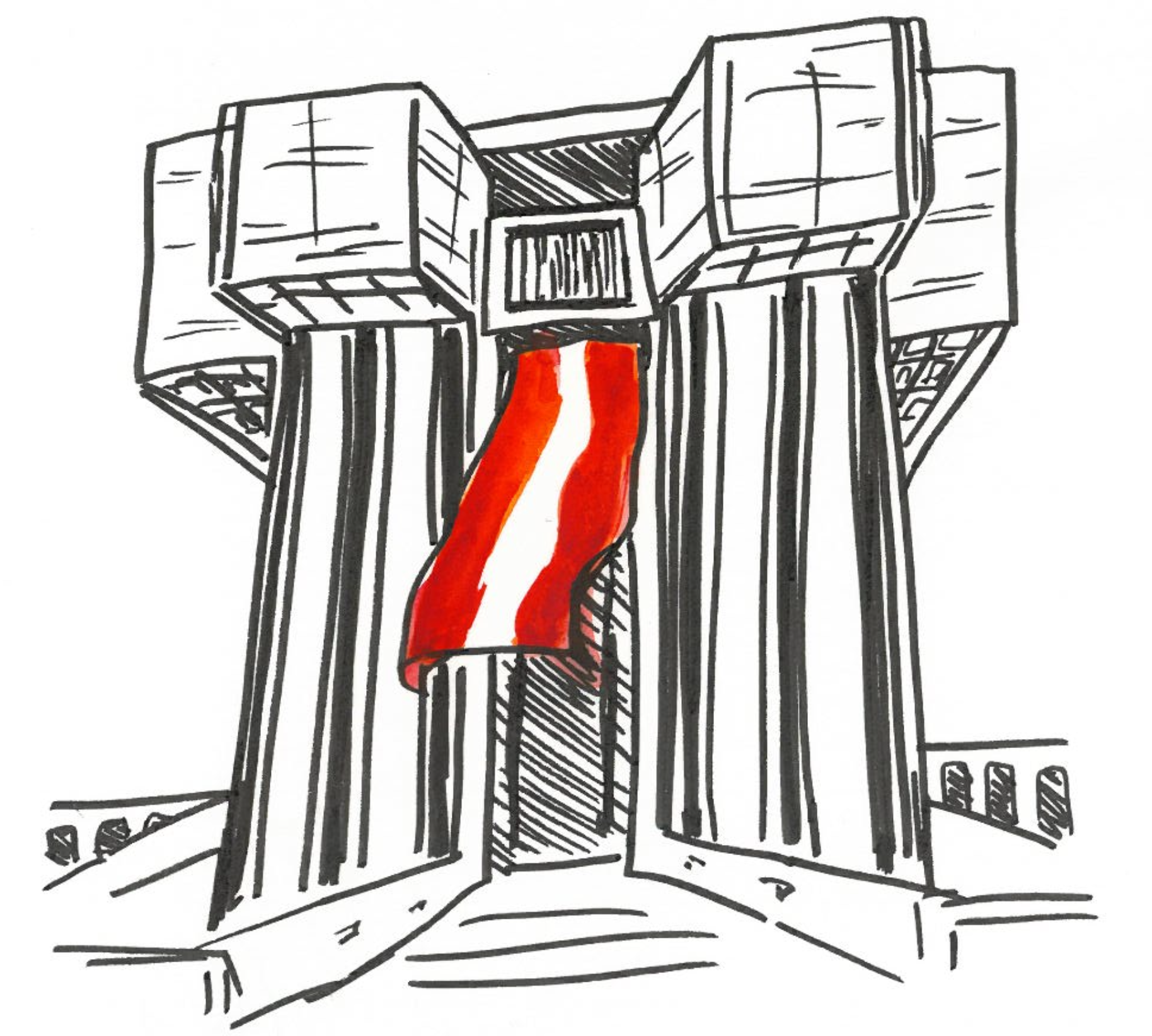

In the distance, looming over the park, a tall and wide brutalist building. Its sharp angles and gray facade grant it an eerie, mysterious aura. You can see it from everywhere in the park, towering over the trees and the pond, watching over the space like a silent sentinel. As you walk around the park, you become aware of a fence separating you from the building. You had noticed it before—thick concrete slabs with openings in between, wide enough for a small dog to go through. But you couldn’t think of it as a fence. Why would there be one? Why would something need to be protected or set apart from this peaceful, lively, and familiar atmosphere?

Your curiosity brings you to peek through the fence, and you catch glimpses of a vast green lawn, small administrative buildings, parked cars, and the imposing tower at the center of it all. And then you see them: men in camouflage suits, carrying shotguns, patrolling the grounds. They stand like statues, unmoving and watchful, guarding the space. You now understand—El Pentagonito, the place where people come to run, is also a military headquarters.

But perhaps you’re too young for this to be a surprise. It seems like another part of the landscape, another layer of the place you’re coming to know. Every country needs a military, you think, and this is simply where ours happens to be. And that is exactly where it has been all along, way before you even existed.

It was January 1971 when, under the military dictatorship of Juan Velasco Alvarado, Major Ernesto Montagne, the Commander General of the Army and Minister of War, announced the decision to build new premises for the Peruvian Military Headquarters. The premises, to be erected in an unpopulated 95-hectare area located in what back then was the Santiago de Surco district, would respond to the need to centralize all organizations of the War Sector, which at the time found themselves dispersed. Architects Juan Gunther and Martin Tanaka were selected to create a building complex that corresponded with the institutional, monumental, and formalist image, as well as the sense of hierarchy and authority that the military government was attempting to establish. They couldn’t anticipate, however, when the project was initially sketched out, that the place would someday turn into what it is today. The area, now belonging to the district of San Borja, went through a period of radical urbanization, as well as through multiple projects of reforestation, which have all resulted in the place where you now stand—the coexistence of military life with the epitome of familial and healthful civilian living. The forest-like atmosphere, the little pond, the running course, and the amenities center were not part of the initial plan. It all gradually came to be, more out of municipal initiatives than by military design.

Originally intended as a symbol of military strength, the sense of hierarchy and authority has now been neutralized, and the original symbolic meaning of the place has been superseded. You witness this as you grow older and get permission to bike around the city on your own. Your friends message you saying, “Vamos al Pentagonito! Vamos al Penta!” and you know that neither you nor them have in mind the military headquarters. Instead, you think of the running course, the pond, and the endless landscape of trees—instead, you think of the thrill of youth and the comfort of friendship.

To get to El Pentagonito from home, you exit your neighborhood and turn right, into Caminos del Inca Ave. You then get to Angamos Ave., which separates the residential district of Santiago de Surco from the district of San Borja, a few blocks away from El Pentagonito. Despite the closeness, you can barely see any runners or bikers. Instead, you see chaos: unregulated combi vans, children selling frugelés, jugglers asking for money after putting on a show, unworking traffic lights, and people violently pacing the streets, going where they have to be. You are also going where you have to be: El Pentagonito.

Once you cross the avenue, you are back to the calmness, to the stillness of being in a park, with the brutalist tower always watching over you. You think of how strange the place is and how it has attained some form of a symbiotic relationship. The location of the Military Headquarters in the middle of the district of San Borja has given place to one of the safest and calmest areas in the entire city; however—and you begin to understand this as you move past the bliss of youth—it is also through the image of familial living propitiated by the surrounding parks that the violence and brutality of military life gets to be concealed.

A few years later, you finally understand where the name of the place comes from. El Pentagonito translates to Little Pentagon, alluding, without any logical reason beyond mere fanatism, to the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. You tell your friends about this on your way there, and they all seem surprised. “That is so obvious,” they claim, and yet none of them had ever realized. It was right there, in front of us, all along. Once there, you see the newlyweds, the quinceañeras, and the kids approaching the thick concrete slabs. You spend the afternoon biking in circles around El Pentagonito, and you laugh at the irony: the park named after a pentagon has no corners at all.