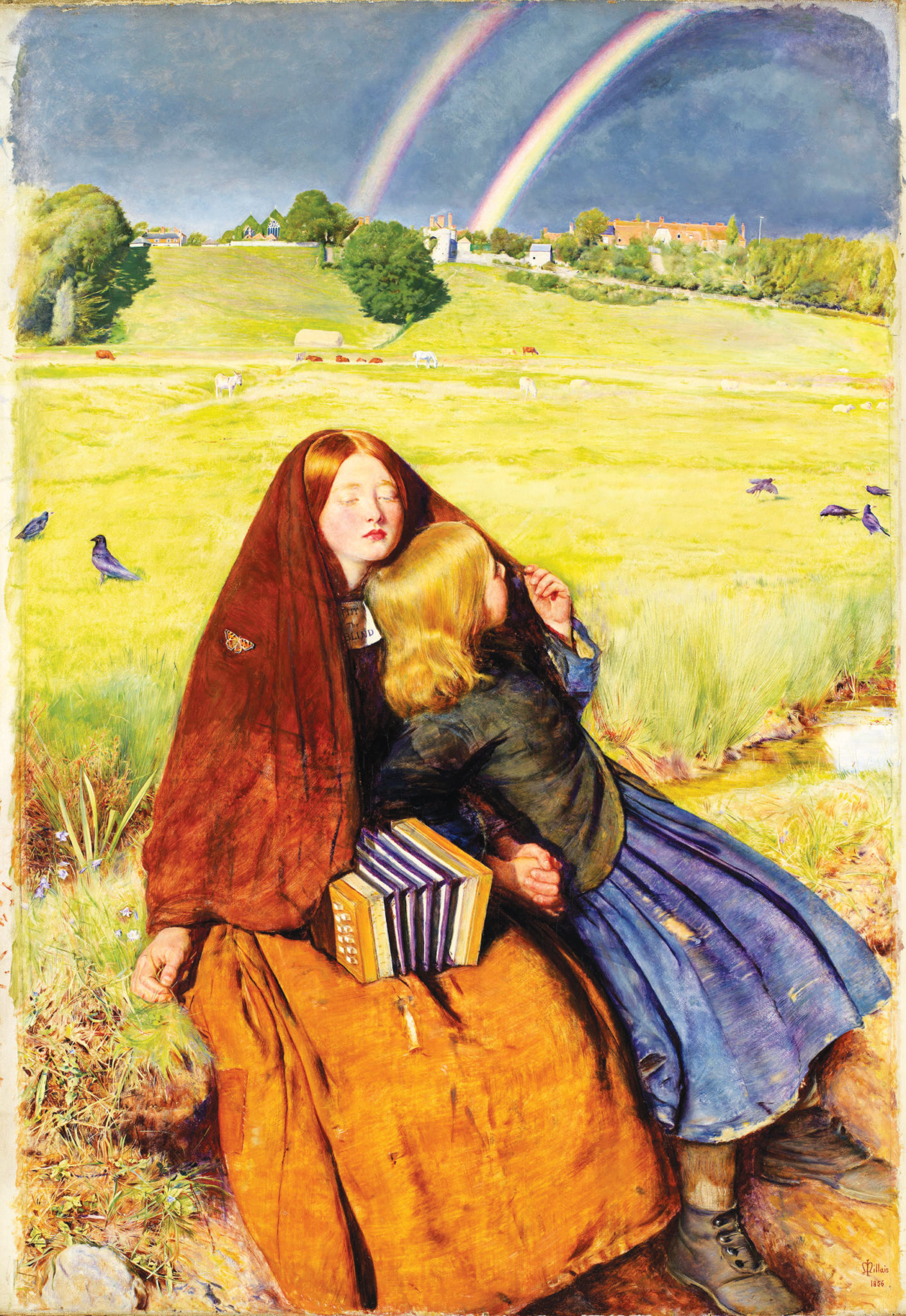

Courtesy of the Birmingham Museums Trust

Amidst the cruelty and pollution of the Industrial Revolution in 19th-century Britain, a group of artists and designers dared to imagine a better world. A new exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art, called “Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement,” immortalizes their vision.

On view from Feb. 13 to May 10, the exhibition features approximately 145 paintings and objects. These were created by artists and designers such as Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddall.

“[The show] is about artists engaging with the industrial world, finding fault with it, and offering solutions,” said Tim Barringer, Paul Mellon Professor in the history of art and one of the exhibition’s curators. “It is ultimately about the belief that beauty can overcome ugliness and cruelty.”

All works on view are from museum collections in Birmingham, U.K. Barringer said the Birmingham galleries wished to draw attention to their collections, and thus, the Birmingham Museums Trust and the American Federation of Arts organized this traveling exhibition. Since the YCBA is “the premier venue” for British art outside the U.K., the AFA was “thrilled” when the YCBA agreed to be a venue. After May 10, the show will travel to Reno, Pittsburgh and Puerto Rico.

Courtney Skipton Long, acting assistant curator of prints and drawings at the YCBA and the exhibit’s organizing curator, said the show is fantastic because it highlights the development of fine and decorative art from the mid- to late-19th century. Since the YCBA is a “stronghold” of British art created up to this time period, the show expands upon the center’s current collection and furthers Paul Mellon’s project of showcasing British art.

The exhibition focuses on three generations of artists and designers who responded to the rise of industrialization by revolutionizing art in Victorian Britain. It follows three distinct movements: the Pre-Raphaelites in the 1850s, the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism from the 1860s to the 1870s and craftspeople’s utopian imaginations from the 1890s to the 1900s.

According to Barringer, Birmingham was a wealthy industrial city where innovation, metalwork and engineering thrived. Yet at the same time, it was regarded by some as filthy, cruel and polluted. The show begins with a series of juxtapositions that contend with this tension. Three intricate art objects contrast a blow-up of Birmingham city; a machine-made carpet with new textile dyes lies alongside a hand-embroidered and hand-dyed bedcover made Mary Jane Newill 58 years later.

“This is key to the exhibition: how artists and designers cope with this new world,” Barringer said. “The bedcover embodies a total rejection of the machine world; you can imagine out of this textile a future in which all the cruelty of the factory and vulgarity of factory-produced objects is forgotten.”

Barringer added that, while the handmade bedcover appears to come from an earlier period, it is “imagining a dreamscape in the future.”

Works in the exhibition reject the conventions of Victorian art and approach themes such as gender, the working class and beauty in novel ways. Barringer noted the significance of two paintings in particular: John Everett Millais’ “The Blind Girl” and Simeon Solomon’s “Bacchus.” He said that Millais’ work, in its poignant depiction of poverty and disability, offers “unflinching realism” and a “new way of looking at the world.” Solomon’s androgynous portrayal of Bacchus is a radically pioneering “blending of male and female identity.”

Along with paintings, the show includes drawings, watercolors, textiles, metalwork and ceramics. Both Barringer and Long noted that the inclusion of material objects is unusual for the YCBA, as the center traditionally exhibits paintings. Decorative art objects in the exhibit demonstrate the reworking of industrially used metal and glass in artistic ways. The craftspeople’s designs prioritize skill and invention over wealth and “revitalize an appreciation of art for art’s sake,” Long said.

Edward Cooke, Charles F. Montgomery Professor of American decorative arts, described the exhibition as a “real feast.”

Cooke said the exhibition offers an incredible opportunity to examine Britain’s industrial midlands from the perspective of Pre-Raphaelite painters, industrialists who collected these painters’ works and shop owners who produced metal and enamel work.

Barringer noted that, interestingly, the exhibition’s themes seem more timely now than they did when he taught this material 25 years ago.

“The questions that these artists addressed — questions of pollution, the loss of nature and social inequality, seem more urgent now than they did near the end of the last century,” Barringer said. “The solutions [the exhibition] offers have strange resonances with much of what is going on today, in terms of organic materials and a suspicion of mass production.”

Cooke said that, in several ways, the exhibit responds to the alienation of the industrial world, which ranges from aesthetic degradation to struggles for workers’ rights.

“What you see is a real celebration of the human will to create objects that are meaningful and wonderful to engage with and look at,” Cooke added.

The Yale Center for British Art is located at 1080 Chapel St.

Freya Savla | freya.savla@yale.edu

Correction, Feb. 20: A previous version of this article referred to Newill’s handmade bedcover as a carpet.