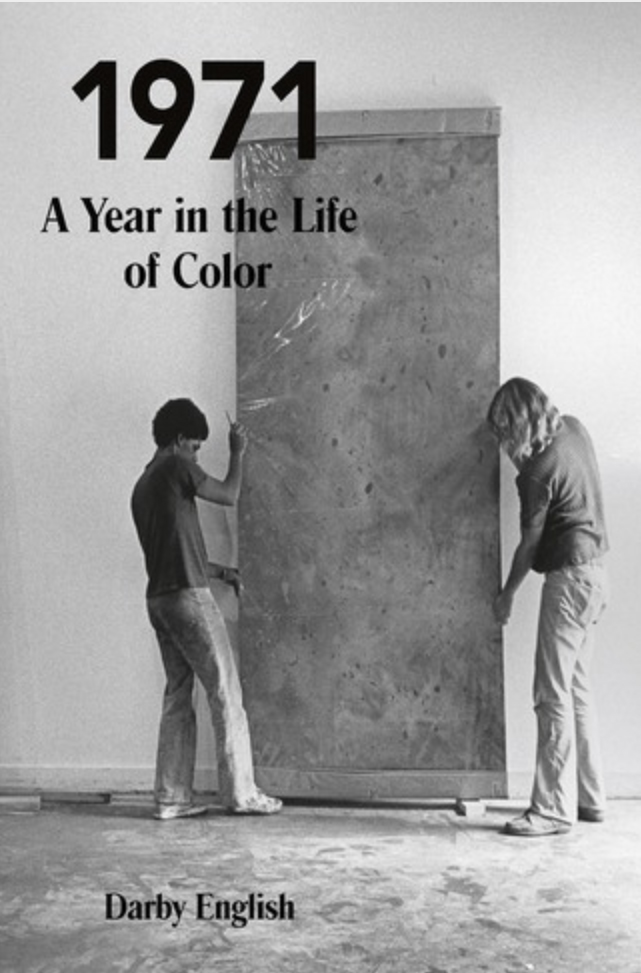

Courtesy of Yale School of Art

“The most important and pressing questions were for myself,” Darby English said. English, professor of Art History at the University of Chicago, visited the School of Art on Monday, Sept. 25th, to discuss his book “1971: A Year in the Life of Color.” “Why hadn’t I just figured it out?”

English was referring to a cache of black modernists whom museum, gallery and institutional narratives had consistently overlooked. These artists had been active since the 1950s. When English encountered their extraordinary work late in 2006, he felt a need to bring their work into the public eye. His research culminated in “1971,” which was published last November.

1971 documents “Contemporary Black Art in America” and “The De Luxe Show,” two exhibitions held in 1971 at the Whitney Museum in New York City and the De Luxe Theater in Houston respectively. Both featured artists English loves, including Ed Clark, Barbara Chase-Riboud and William T. Williams. Both provided insight into a fundamental question of English’s’ studies: How can we move past racialized readings of black American art?

The notion that all work produced by black artists has to be an explicit commentary on their blackness pervades every corner of the art community. English may sermonize on the imprudence, even peril, of such a sentiment, but many others, including black American artists, have reinforced and continue to reinforce the idea. Jacob Lawrence, arguably the most prominent black painter of the 20th century, garnered his fame through the portrayal of African-American history, most notably the Great Migration and the Haitian Revolution. English, while discussing Tom Lloyd, a black artist best known for his geometric arrays of industrial lamps, divulged that Lloyd himself strongly believed that black art was identified “because when black people see it, they know a black guy made that.”

At this moment English paused, then turned and addressed the crowd. “You should be laughing.”

English is not the first to hold this perspective. In 1967 black modernist painter Richard Saunders published a pamphlet, titled “Black is a Color,” in which he argued that an African-American artist conforming to racial hang-ups “may risk becoming a mere cypher, a walking protest, a politically described stereotype, negating his own mystery and allowing himself to be shuffled off into an arid overall mystique.”

Not all black modernists mentioned sought explicitly to explore the African-American experience. Ed Clark’s “Untitled” is an abstract quilt of brushstrokes with raw physicality and dynamic color that break the traditional rectangular limits of a canvas. It contains no elegy, no endorsement, no entreaty. It also was held in the storehouses of the Art Institute of Chicago, not once being put on display, for twelve years.

So goes the Catch-22: Black artists, seeking to emancipate themselves from overtly racialized interpretations of their art, must either adopt this oversimplified analysis or consign themselves to invisibility. Though both exhibitions discussed in “1971” feature similarly sidelined artists, they figure into the opposing ends of this narrative.

The concept of “Contemporary Black Artists in America” was struck up by the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), a fringe organization formed in response to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Harlem on my Mind” exhibit, which neglected to include the contributions of black painters and sculptors to the Harlem community. The BECC urged the Whitney to mount a show for the support and promotion of black artists throughout the United States, delineated by 12 criteria.

The Whitney failed to meet just one: the employment of a black curator. The BECC protested against the employment of white curator Robert M. Doty, arguing that his distance from the black experience made him unfit to compose an exhibit. Fifteen of the 75 artists slated to appear dropped out. When the show finally materialized it was haphazard and incomprehensive, the product of a black vision parsed through a white mind.

The “De Luxe Show,” in contrast, was assembled by the African-American painter Peter Bradley. It was the first large-scale, racially integrated art exhibit in the United States. Staged in a renovated movie theater in Houston’s Fifth Ward, on a street that no one would go down “unless they were in a car moving fast,” the “De Luxe Show” experienced no level of controversy comparable to its contemporary at the Whitney, though perhaps to its detriment. The only press coverage the exhibit received was by an architecture magazine, which focused on how a dilapidated, rat-infested space had suddenly become habitable.

Remarkably, children found the show most engaging, playing amidst the paintings of Larry Poons and Virginia Jaramillo, climbing on the sturdy metal sculptures of Richard Hunt. The “De Luxe Show” functioned as a sanctum of the marvelously new and free. This made for a good metaphor, yes. But, more importantly, it valorized black contemporary artists on the basis of their individual merit, rather than a conjured link to a black collective.

There is clearly much more to be done in recognizing the value of black American modernists. English presents William T. Williams, Al Loving and Frank Stella as artists who demonstrate the conundrum. All three experimented with geometric forms, highlighting the interplay of color, yet dialogue about Williams and Loving, the two black artists, is sparse, while that about Stella has been exhaustive.

Yet, English provides us with a consolation. Even if we are not having a conversation about the excellence of these artists’ work, we may have a conversation about the “boldness of their work.” After all, the artists English celebrates create art that both encompass and transcend race. Rather than fixating on the cultural and political implications of color, both in skin and on the canvas, they created exemplary modernist art.

Brianna Wu | brianna.wu@yale.edu