Sam Berek

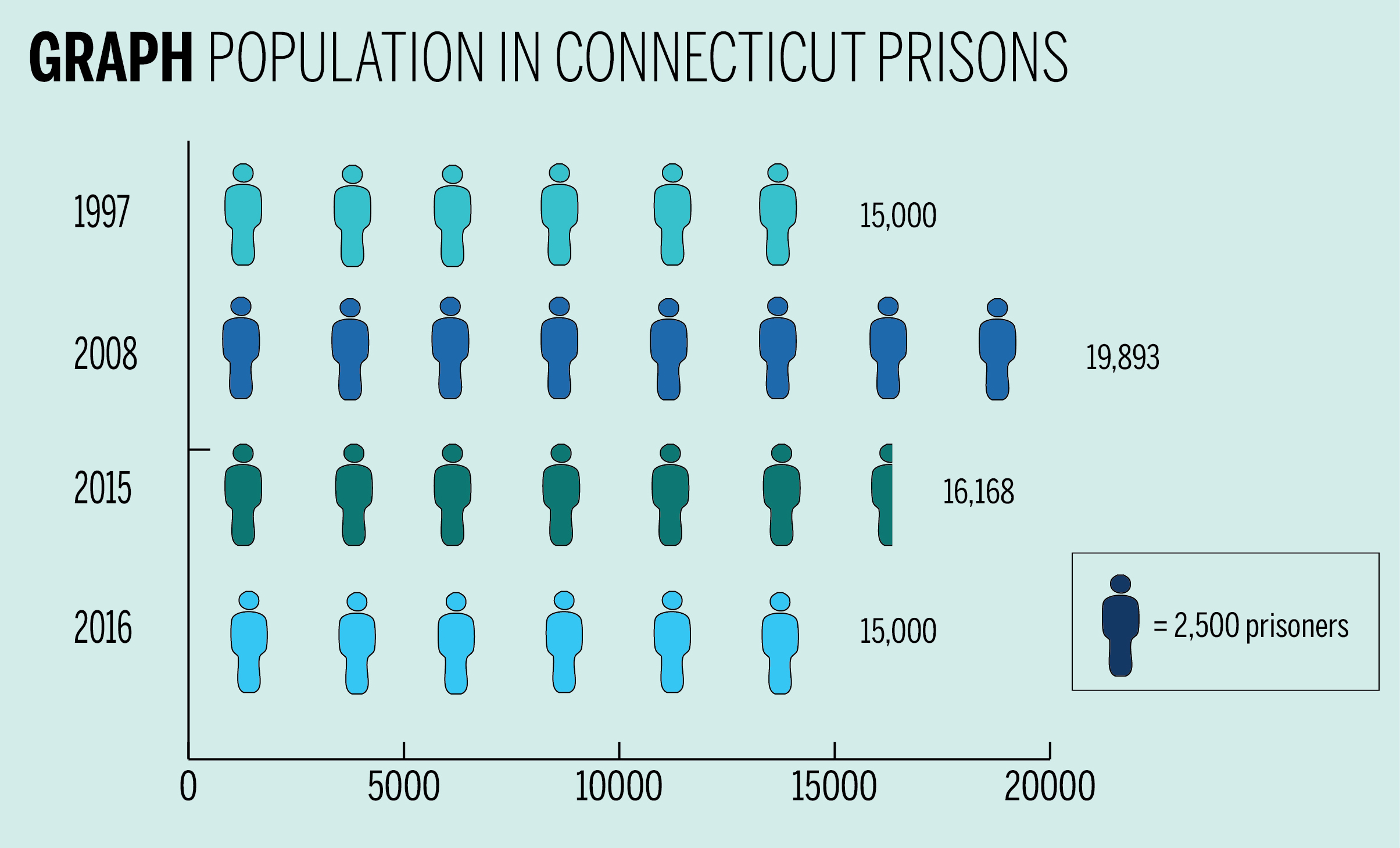

Gov. Dannel Malloy’s efforts to place criminal justice reform at the forefront of his domestic agenda have begun to pay off, as he announced last week that Connecticut’s prison population briefly dropped below 15,000 — where it now hovers — for the first time in nearly two decades.

Connecticut’s current total prison population is down by nearly 25 percent from its all-time high of just under 20,000 in 2008, and down 7 percent from 16,168 in September 2015. Standing alongside corrections officials from around the state on Sept. 9, including Correction Commissioner Scott Semple, Malloy credited the “Second Chance Society,” the criminal-justice reform efforts he has fought for over the last two years, with playing a major role in reducing Connecticut’s prison population.

Malloy framed the state’s success in reducing its prison population as part of a broader effort to restructure society, with the intent of lowering crime rates and improving quality-of-life metrics in communities across the state.

“We can’t be a punitive society,” Malloy said, singling out the school-to-prison pipeline for criticism. “We can’t permanently punish nonviolent offenders for the rest of their lives, swelling our prisons and making lifetime criminals out of people who made mistakes. We must be focused on effective solutions that break the cycle of crime and make our communities safer.”

Semple said Friday’s announcement, held outside the Hartford Correctional Center, marks a “turning point” — not merely in statistics about the prison population, but also in “efforts to change the way we think about crime and punishment.” Connecticut’s success, Semple said, has made Malloy into a national leader on criminal-justice reform.

Much of the reduction in the overall prison population has come not only from lowering maximum sentences, but also from sending fewer people to prison.

One example of that method, Malloy said, is in new penalties for drug possession. Under the old system, most drug possession were unclassified felonies that could leave the offender facing seven years in prison. Under Malloy’s reforms made in 2015, most drug possessions now count as merely a Class A misdemeanors, carrying a maximum of one year in prison.

Reductions in the prison population can serve a societal good but also a narrower fiscal one. On average, a single inmate costs taxpayers $168 per day, and tens of thousands of dollars per year. The savings from a smaller prison population, Malloy said, are already paying off: The budget for corrections has fallen by $60 million — due in part to state budget cuts — while three prisons and three sections of other prisons have closed.

Semple added that the lower prison population, in addition to changes in practices, has had some positive impact on the environment inside prisons, but that problems still need to be addressed.

“We’ve become much more incentive-based in terms of what we do, preparing to be accountable to folks that are accountable to themselves,” Semple said. “But at the same time, there are individuals who just don’t get it, and we have to be responsive to those kinds of issues. Overall, I think the climate is in a good place right now, and if you measure that against incident rates, there’s some indication that we’re having success.”

Support for legislative action on reducing Connecticut’s prison population has come largely from the American Civil Liberties Union and Connecticut’s branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Scot X. Esdaile, president of the Connecticut NAACP, said the fall in number of state prisoners is a welcome statistic, but by no means the end of the struggle. More work needs to be done on reintegrating prisoners once they return home, especially on helping them find jobs.

“We still haven’t been able to put urban America back to work,” Esdaile told the News on Monday. “90 percent are really working hard to get jobs, and that’s why it’s really important we make the adjustments to put them back to work. The key is that we have to have the elected officials work tirelessly and have some measurable results in putting people back to work.”

Esdaile added that the experience of the current nationwide heroin epidemic, which has hit working-class white communities hard, seems to have taught lawmakers lessons that would have been better learned in the “war on drugs” years of the 1980s and 1990s, when police tackled the crack epidemic with a “zero-tolerance, militant approach.”

Esdaile praised Malloy’s approach to dealing with drug possession, calling it a “smarter and more intellectual way” of addressing the problem.

The Second Chance Society initiatives — touted by liberals around the nation as an example of commendable progress on criminal justice reforms — have proved popular in Hartford.

In 2015, Malloy’s proposals managed to garner the support of state Senate Minority Leader Len Fasano ’81, R-North Haven, and state House Minority Leader Themis Klarides, R-Derby. Those proposals formed the bulk of what Malloy credited with the reduction in the prison population — lowering penalties for drug possession and eliminating mandatory sentencing minimums for drug possession in a school zone.

In the past legislative session, though, Malloy’s second round of reforms, dubbed “Second Chance Society 2.0,” met a steelier reception. This time around, Malloy’s dual proposals — to consider offenders up to age 20 as juveniles and eliminating bail for numerous misdemeanors — might have helped to reduce the prison population, but they died at the hands of skeptical lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

Semple has led the Department of Correction since January 2015.