Woolsey Hall was unbearably hot one morning last August. As hundreds of Freshman Assembly attendees fanned themselves with paper programs, University President Peter Salovey stood to speak.

Having only moved into the president’s office in Woodbridge Hall the previous month, Salovey was a freshman in his own right. The speech he was about to deliver would be his first major public address at the helm of the University, and it would work to set the tone for his presidency.

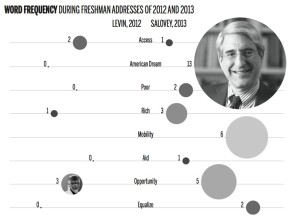

Less than 100 yards from Beinecke Plaza — the longtime site of Yale protests for civil rights and against the Vietnam War, apartheid and, most recently, fossil fuels — Salovey took on the issue of the day: inequality. But he did so through the lens of the University.

“This morning I worry about whether the American Dream is still possible and whether education is still the best ‘ticket’ to socioeconomic mobility,” Salovey said.

Less than six months later, Salovey filed into the White House with over 100 other university presidents. They had been called to the White House as part of President Barack Obama’s effort to make higher education more accessible to qualified students, regardless of means.

Salovey’s freshman address and visit to the White House reflect two connected facets of the Yale president’s job. In both, he took a stance on the accessibility of higher education, an issue relevant to Yale and to the nation at large. In doing so, he followed a host of Yale presidents before him.

“Because Yale is one of the world’s great universities, its presidency is naturally a public position,” Morse College Master Amy Hungerford said.

In Washington, the president is a representative of Yale and, more broadly, higher education. His constituency: Yale’s faculty and students.

At Yale, the president works to set the tone for the University, to lead this diverse constituency to coalesce on a small set of issues and goals.

From time to time, these two roles intersect. It is then that Yale presidents have been most remembered for “speaking out” on an issue. For Kingman Brewster, it was the Vietnam War and civil rights. For Richard Levin, it was globalization.

“I think being a university president does allow one access to government leaders, to the media, and in that sense can be thought of as a bully pulpit,” Salovey said.

In Salovey’s first year, these dual roles have comes together on the question of access to a Yale education and, by extension, socioeconomic inequality and Yale and beyond.

PICKING THE ISSUES CAREFULLY

“Given President Salovey’s commitment to a ‘unified Yale,’ there are constraints on the kind of issues he might speak out on,” English professor Wai Chee Dimock ’82 said. “These constraints would apply to any university president. They are important to keep Yale as a working environment, marginalizing no one, hospitable to all points of view on divisive issues.”

Students, faculty and staff are not the only members of the Yale community that span the political spectrum — alumni do too. Charles Johnson ’54, who donated $250 million to Yale in October — the largest gift in the University’s history — is one of the top Republican donors in the country. Other alumni, such as Bill Clinton LAW ’73, have led the Democratic Party to the American presidency.

Salovey demurred when asked about his personal political views, emphasizing that he cannot speak as Peter Salovey — psychology professor and New Haven resident — without being heard as the primary representative of Yale University.

“I’m always a little reluctant to talk too much about personal politics because it gets coated as the president of Yale says blah, blah, blah,” Salovey said. “It reflects on the institution.”

As donating to a political candidate is tantamount to a verbal endorsement, Salovey also does not make political donations of any kind.

“It’s less the issue of trying to please people. It’s more the issue of wanting access to anyone I’d like to talk to,” Salovey said. “I need to talk to people on both sides of the aisle … and if I make political contributions they’re going to be partisan.”

While former Yale administrator Henry “Sam” Chauncey ’57, along with dozens of faculty and students interviewed, agreed that the Yale president should avoid partisan issues, he said the president still has a responsibility to occasionally engage on matters of public policy relevant to the University.

“The tool I have most at my disposal is verbal exhortation. But as a behavioral psychologist, I know that verbal exhortation is not typically the key to behavior change in others.

Thus far, Salovey has expressed his views on three issues: immigration reform for highly skilled workers, federal funding for research and, most of all, access to higher education.

In August, he released a statement applauding 68 senators who voted to pass the Border Security, Economic Opportunity and Immigration Modernization Act, a bill Yale had lobbied on. In the same statement, he also threw his support behind the DREAM Act, which provides a path to citizenship for those brought to the United States as children, as well as legislation reforming immigration policies for the highly educated.

In January, Salovey spoke out again when he decried the American Studies Association’s boycott of Israel.

“As a university president, I believe that the pursuit of knowledge should not be impeded, and therefore a boycott is a strategy I cannot endorse, interfering as it does with academic freedom,” Salovey told the News in a January email. “In this matter I am expressing my own opinion, but one informed by my position as Yale’s president.”

Still, there are many issues that Salovey has avoided.

After months of nationwide student campaigns to push universities to divest from the fossil fuel industry, administrations at many universities have responded definitively — one way or another — to students’ complaints.

In October, Harvard University President Drew Gilpin Faust released a statement saying that Harvard would not divest. Just last week, Faust released another statement announcing new research and sustainability efforts to help fight climate change.

Despite several student protests on the Yale campus, Salovey has stayed quiet about the issue of divestment and climate change, though he has stated that he is personally concerned about global warming.

When asked what issues he might take public stances on in the future, Salovey was cautious, saying that the Yale community would need to be aligned on any issue.

A FOCUS ON ACCESS

Salovey’s decision to engage on the topic of access to higher education — and by extension, socioeconomic inequality — appears to have been an easy one. First, his interest in the topic is personal, as his own family’s story is a testament to the power of higher education as a vehicle of social mobility.

Salovey’s father grew up in the Bronx, the son of immigrants from Warsaw and Jerusalem. Through education, he was able to overcome the hardships of his childhood. Today, Salovey’s parents live in Palos Verdes, an affluent coastal suburb in California.

But Salovey also sees that Yale has a role to play in mitigating socioeconomic inequality by increasingly opening the gates of higher education to more of those who cannot afford it.

“A topic like inequality ends up having an important component to do with higher education, because at least historically education was viewed as one of the more effective mechanisms that allowed for social mobility or economic mobility,” Salovey said. “I think it’s important that that not be seen as the only or primary role of education, but it is an important role of education.”

Still, increasing access to higher education is not so easy to do. Though they have the same objective, universities and the federal government are currently engaged in a tug-of-war over who should foot the bills for the mounting costs of higher education.

At the January White House summit, senior members of the Obama administration — including then-National Economic Council Director Gene Sperling and Obama himself — placed the onus for increasing access and reigning in higher education costs on colleges and universities. Even to attend the conference, university presidents had to arrive with clear commitments in hand.

But for their part, institutions of higher education and the associations that unite their Washington-based advocacy have repeatedly sought more help from the federal government.

“To make this work you cannot exclusively rely on colleges and universities,” Salovey said after the summit. “Nor can you exclusively rely on government funding.”

Salovey said it is important to make clear that ensuring access is a partnership between universities and the federal government. The University must lead by example with the allocation of its resources, notably through an aggressive financial aid policy, he said.

But to make the kind of gesture Salovey did during the freshman address, Salovey also needs the monetary backing of the federal government. The Yale president cannot wax poetic about the inherent values of providing a Yale education to all who deserve it if the University does not have the funds to do so.

In his freshman address, Salovey made the importance of the federal government plain by mentioning four pieces of legislation: the Morrill Acts — which created land grant colleges — the GI Bill, Title IV and the Federal Pell Grant Program. Together, the acts have helped tens of millions of Americans receive college educations.

“These investments are worth making because college graduates develop broad and deep knowledge, sharp critical thinking and communication skills and the ability to work collaboratively,” Salovey said. “And as a result, they are three times as likely as those without a degree to move from the lowest levels of family income to the top level.”

Those words could have been delivered to a roomful of policymakers as easily as they could have to the freshmen in Woolsey Hall.

Salovey said his words on that hot August day were more than an exhortation to Yale’s youngest cohort of students. Rather, they were an act of statesmanship, an address meant to be read as much in the halls of the Capitol as in those of Linsley-Chittenden.

“I’m conscious of the fact that a speech like that might be read beyond the walls of Yale, indeed, to be frank, I’m hoping it will be,” Salovey said. “I am hoping that a speech like that will in fact stimulate both a campus discussion but also contribute to a conversation that’s happening off campus as well, including in Washington.”

THE CONVERSATION IN WASHINGTON

Like many other university presidents, Salovey visits Washington, D.C. frequently. Since taking office last July, Salovey has already made his way to the capital no fewer than three times to discuss higher education with members of Congress — 18 of whom attended Yale — senior members of various federal agencies and, at times, groups of other university presidents.

Although the meeting agendas differ every time — and are more often than not confidential — administrators interviewed identified two major issues frequently addressed: financial aid and accessibility, and federal grants and contracts.

At the most basic level, Salovey’s goal is always the same: to persuade policymakers that what is good for Yale is also good for the country.

In particular, University Vice President for Strategic and Global Initiatives Linda Lorimer said Salovey works to advocate for increased federal investment in science and medicine as a way of furthering “the country’s success.”

Salovey is just one of the many university presidents who make their way to the capital. William Bonvillian, head of federal relations for MIT, said MIT President Rafael Raif is a frequent visitor to Washington. Kevin Galvin, Harvard’s Senior Director of Public Affairs and Communications, said that Harvard’s Washington Office works closely with Harvard’s President Faust to develop strategies for partnerships between Harvard and the federal government.

And when university presidents speak, policymakers say they listen.

California Congresswoman Lois Capps DIV ’64 said that university presidents have unique perspectives on federal issues, from student financial aid to federal research funding to immigration. Capps was part of a group of Yale alumni in Congress who met with Salovey last July.

“In order to advocate on behalf of students and higher education, meeting with campus leaders like President Salovey is important to identify additional ways to best serve the interests of students not only in my Congressional district, but also students at schools and universities across the country,” she said.

Elizabeth Esty LAW ’85, who has also met with Salovey, expressed a similar sentiment, adding that presidents such as Salovey have given her insight into how she can support students, faculty, staff and communities around universities.

But Salovey cannot be a permanent presence in Washington. Back at Yale, other issues call — searches for new deans, fundraising and a multiplicity of other responsibilities.

For this reason and others, Salovey has at his disposal a full-time office designed to be his eyes, ears and voice in the capital: Yale’s office of federal relations.

Richard Jacob, Yale’s associate vice president for federal and state relations, and his deputy, Kara Haas, travel frequently to Washington, though Yale’s office of federal relations is based in New Haven. To effectively articulate how an issue impacts the University, Jacob said the office needs to understand Yale, and the best way to do that is to be on campus.

Yale’s federal relations office also keeps a quieter profile than some of its peers. In contrast with New York University’s federal relations office, which maintains an active webpage that encourages alumni to lobby their elected representatives on issues relevant to NYU, the Yale office’s web presence is bare bones.

But while Yale may speak softly, it carries a big stick in the capital. In 2013, the University spent $590,000 on lobbying-related expenses. Harvard, by comparison, spent $530,000, while Princeton spent $280,000.

Of the 17 pieces of legislation Yale lobbied on in 2013, Harvard and Princeton both lobbied on seven. Another five were lobbied on by either Harvard or Princeton, but not both.

An undisclosed portion of Yale’s lobbying spending also goes toward membership dues for a variety of higher-education organizations, such as the Association of American Universities (AAU), the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU) and the Science Coalition, among others.

These organizations partner with a variety of other groups — some of which University spokesman Tom Conroy said directly employ lobbying firms — to create a sprawling network of Washington-based advocacy.–

“These play a key role in collecting university concerns and speaking for overall university interests and concerns,” Bonvillian said.

Although the AAU’s annual meeting of 62 colleges presidents in Washington is confidential, Salovey said the major topic is typically how universities can persuade the federal government to better support research and teaching at universities across the country.

LEADING FROM WITHIN

Salovey said the discussion of access he began during his freshman address was not just about the University opening its gates — it was also about encouraging Yale graduates to do the same for others.

“I do think we have an obligation to put that education that we receive to a good use, to figure out ways to give back, to figure out ways to encourage others to obtain a similar kind of education,” Salovey said.

Students interviewed said some of the issues raised in Salovey’s freshman address have stuck with them.

Emmet Hedin ’17 described the speech as “an affirmation of the importance of education,” while Russell Cohen ’17 said the president’s address has set the tone for his time at Yale.

Emmet Hedin ’17 described the speech as “an affirmation of the importance of education,” while Russell Cohen ’17 said the president’s address has set the tone for his time at Yale.

Isiah Cruz ’17 said that Salovey’s freshman address had played a role in encouraging him to help reduce socioeconomic inequality, in an as-of-yet undetermined capacity, following graduation.

As president, Salovey is responsible for the “moral custodianship of the University,” political science professor Steven Smith said.

“We are not just purveyors of value-neutral information, but should be teachers of moral values like responsibility, service, and preservers of an intellectual heritage and tradition,” Smith said. “If we at the University don’t care about these things, who will?”

The question is whether anyone will listen.

Sometimes a sweating freshman in Woolsey Hall can be tougher to get through to than a senator.

“The tool I have most at my disposal is verbal exhortation. But as a behavioral psychologist, I know that verbal exhortation is not typically the key to behavior change in others,” Salovey said. “On the other hand, trying to lead by example and help students develop their own sense of efficacy in leading a life of purpose is likely to be more effective.”